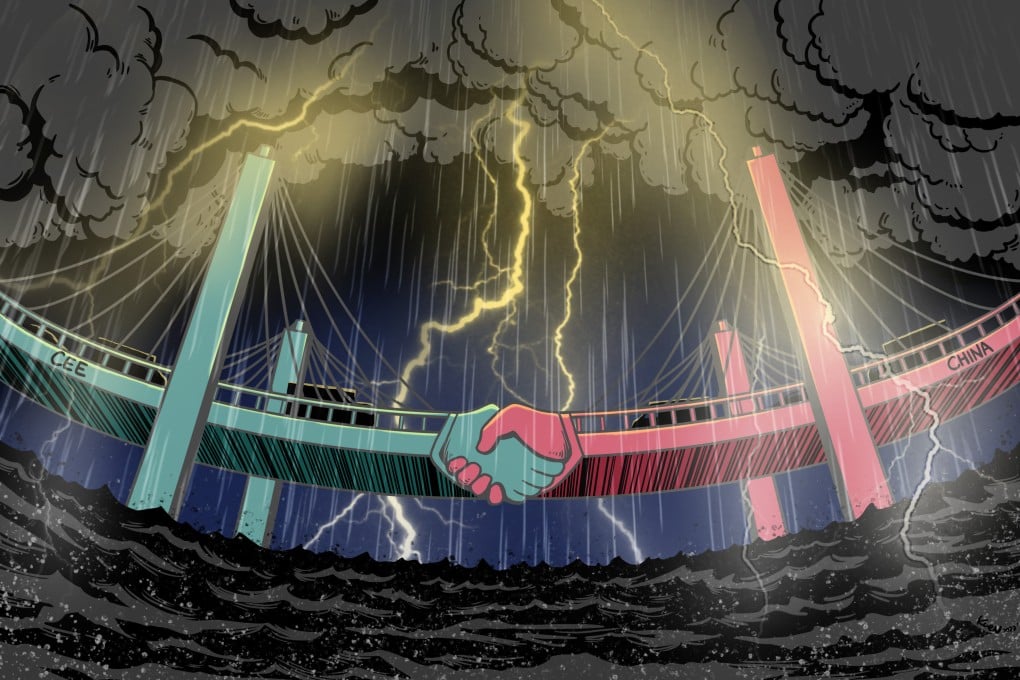

Croatia’s China-built, EU-funded bridge to open over troubled waters

- Beijing’s way of doing business and its rigid Covid-19 response have damaged its relationships in key belt and road corridor, experts say

- Chinese investors dried up during the coronavirus pandemic but with war in Ukraine and new EU finance opportunities, they may not be as welcome this time round

On a glistening white bridge suspended above the deep blue Adriatic Sea off Croatia, engineer Davor Peric proudly shows off the smooth layer of asphalt stretching across its length.

This asphalt, specially designed to withstand salt water, is a Croatian product but most of the Pelješac Bridge is not.

And the firm came equipped to impress: more than 70,000 tonnes of steel was cast in Chinese factories and brought to Croatia on seven boats. With it came 22 different vessels, including a crane with a load capacity of 1,000 tonnes, an unusual sight for a region in serious need of infrastructure investment.

“When the Chinese contractors arrived, [China] was already a global power,” said Peric, associate project manager at Croatian Roads, who has been working on the project since its launch in 2018.

“The first part of the project was really showing off their strength – the number of people, the resources, equipment, the mechanisation.”