Why Chinese players are taking private stakes in Africa’s new megaprojects

- Ports in Nigeria and Cameroon illustrate how Chinese firms are shifting to ‘integrated investment, construction, and operation’ model

- Chinese financing and investment in big African infrastructure projects under belt and road fell to a historical low last year

Observers say Chinese firms are shifting from a model that limited them to engineering, procurement, construction plus finance to now taking stakes in running the infrastructure once it is built in a model known as integrated investment, construction, and operation (IICO).

IICO is now commonly used in Chinese discussions on public-private partnerships (PPPs). It refers to a long-term contract which usually entails the design, financing, construction, operation and, in certain cases, toll collection of an asset.

It also comes in the form of build-operate-transfer (BOT), build, own, operate, transfer (BOOT) and build-own-operate (BOO) contracting.

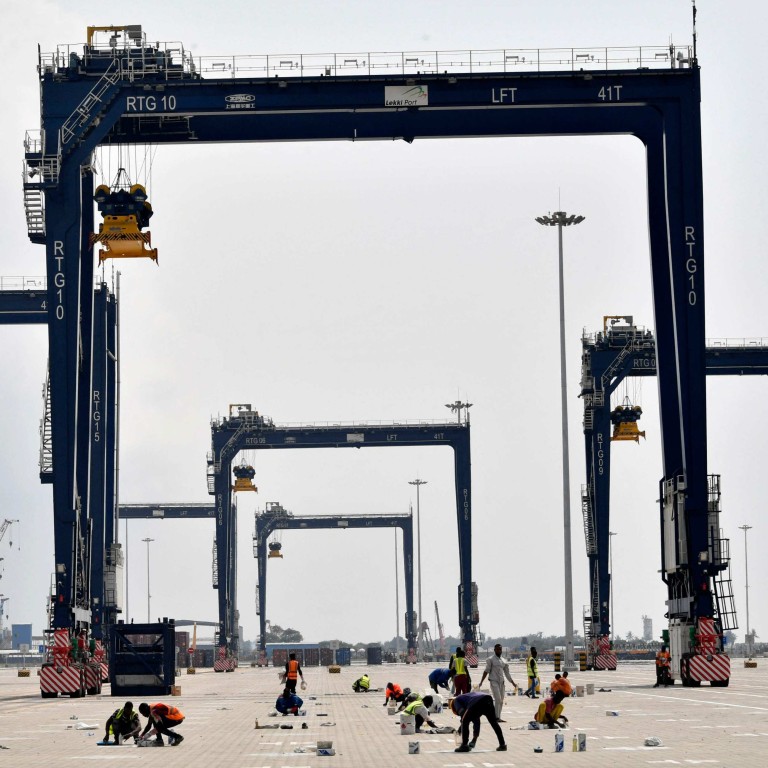

Last month, at the inauguration of the US$1.5 billion Lekki port, Chinese ambassador to Nigeria Cui Jianchun praised the financing model used to build the country’s largest deep seaport. Referring to the port, the ambassador said it was a valuable practice for Chinese companies to move from engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractor to a strategic investor in building major infrastructure projects in Africa.

“The government doesn’t need to worry about the existence of guarantees or debt risks,” Cui said, adding that China would promote this business model for everyone’s benefit.

How Ukraine war has turned Africa into a geopolitical battleground

Lekki port, 64km (40 miles) east of Nigeria’s economic capital Lagos, is expected to help the country meet its growing cargo demand. Two other Lagos terminals – Apapa and Tin Can Island – are shallow and cannot receive large container ships, forcing bigger vessels to call on ports in neighbouring countries before the cargo is shipped to Nigeria in smaller vessels.

Zhang Hui, deputy general manager of the China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation, foreshadowed significant changes to the market, noting in 2021 that the international engineering model centred on design, procurement and construction was shifting to “investment, construction and operation”. The corporation, also known as Sinosure, is China’s policy agency providing insurance for export and outward investment.

“The fiscal investment model in which the host country’s government plays a leading role in investment is evolving into a diversified investment model. The adoption of the PPP model to promote the construction of public infrastructure projects has become an important trend for enterprises to participate in international cooperation,” Zhang told an infrastructure investment and construction forum in Macau in 2021.

By the first half of that year, Sinosure had cumulatively underwritten 221 overseas projects integrating “investment, construction and operation” worth US$56.3 billion, pointing to more Chinese companies taking up the financing model.

The shift to public-private partnerships for Chinese companies comes amid reduced bilateral lending for overseas projects as Chinese lenders take a more cautious approach in financing infrastructure projects.

Hong Zhang, a China public policy postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University’s Ash Centre for Democratic Governance and Innovation, said China Harbour only became an investor in Lekki port after the original developer – Singapore’s Tolaram Group – failed to secure financing from European and Nigerian banks.

Zhang said China Harbour, originally hired by Tolaram as the EPC contractor in 2012, started approaching Tolaram about providing equity investment in 2017. Eventually, they agreed on a 70-30 split in the Lekki Port Investment Holding joint venture with China Harbour taking the majority.

China willing to join debt-relief efforts for poor nations: Li Keqiang

This joint venture in turn holds a 75 per cent stake in the concessionaire responsible for developing Lekki port – together with the Lagos state government (20 per cent) and the Nigerian Ports Authority (5 per cent). The venture won a 45-year concession and has a preferential right for a 25-year renewal.

However, Zhang said the Nigerian partners and Tolaram also demanded the operation be separated from China Harbour’s control for the sake of balance.

“This was how CMA Terminals, a subsidiary of the French shipping conglomerate CMA-CGM, came into the picture … CMA will take an 80 per cent stake in the joint venture with CHEC that will operate Lekki port,” Zhang said in a recent study published by the China-Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

“Importantly, CMA’s guarantee of port traffic helped convince China Harbour’s leaders to greenlight the investment. The two companies already have a history of cooperation, including as joint venture partners for the operation of Cameroon’s Kribi port.”

In 2020, China Harbour injected US$221 million of equity capital into China Harbour Engineering LFTZ Enterprise. China Development Bank then advanced a US$629 million loan facility to build the port with the aim of making Africa’s most populous nation a logistics hub.

Zhang said BOT/BOOT (thus IICO) projects were most likely in the power sector, and some Chinese companies such as Sinohydro and PowerChina had already done business this way for a while. Chinese firms did not have as much experience in roads, another sector seeing a rise in public-private partnerships around the world, Zhang said.

“[China Road and Bridge Corporation] is learning to do it, and this case of Nairobi Expressway is one of their first attempts in Africa, and very worth watching,” she said.

Zhang said the port sector was “quite special because development of new major ports is relatively rare” and Chinese companies had fewer examples to follow, “that’s why Lekki port is so significant”.

Tim Zajontz, a research fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, said the Chinese government had started to encourage Chinese firms to invest in PPPs in African infrastructure markets as early as 2016, when debt sustainability had started to wane in several African countries.

“Beijing has since actively promoted PPPs across Africa as a debtless alternative to loan-financed infrastructure development. However, research shows that PPPs can come with burdensome long-term liabilities for public authorities if not negotiated prudently,” said Zajontz, who is also a research associate with the Second Cold War Observatory, a global collective of scholars concerned with the effects of intensifying power rivalries.

He said the success of China’s belt and road programme in Africa depended on gradually shifting the initiative’s financial governance from sovereign loan finance towards investments in public-private partnerships. Zajontz said Beijing’s active globalisation of the “integrated investment, construction and operation” model was therefore motivated by both economic and political reasons.

He said both private and state-owned Chinese firms were interested in continuing Africa’s infrastructure boom, because they were heavily invested and widely mobilised in African markets.

“With a growing number of African governments unable to take on new loans, the privatisation of infrastructure development is currently returning as the renewed order of the day,” Zajontz said. “Chinese firms will try to capitalise on these market developments by increasingly transforming from being mere contractors to becoming long-term investors and operators of African infrastructure.”

US fears over Chinese military in Africa should focus on Atlantic: analysts

Lauren Johnston, a China-Africa researcher at the South African Institute of International Affairs, said what she found interesting was that Singapore and some Middle Eastern countries were becoming partners as part of the new development trend.

She said Singapore’s Tolaram Group was involved in the Lekki port and Singaporean shipping, and maritime firm Winning International Group, along with Chinese investors, was investing in infrastructure connected to the Simandou iron ore deposit in Guinea.

She said there might be echoes of the type of joint venture enterprises (JVEs) China used in the late 20th century, some of which had sunset clauses at which point they would become fully locally owned.

“These JVEs typically also had explicit local talent training obligations. African companies and governments might take some time to learn from earlier East Asian JVE models, and work out the best equivalent for their own development,” Johnston said.