Advertisement

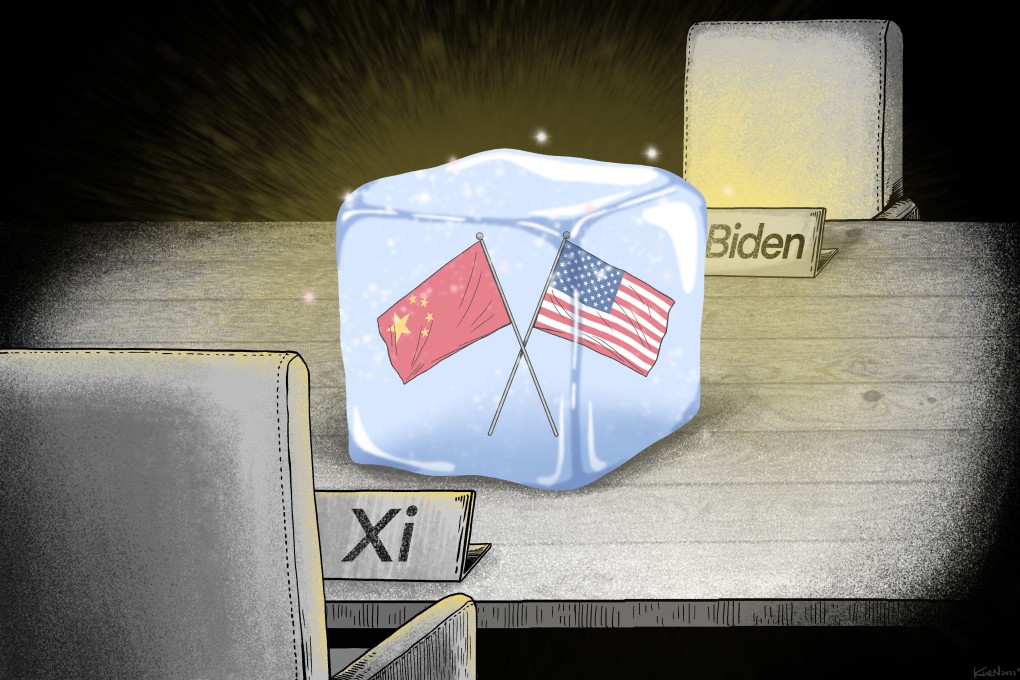

US-China ties: don’t expect any breakthroughs when Xi and Biden meet, analysts say

- The White House has confirmed that a leaders’ summit will go ahead in San Francisco this month

- ‘No major thaw’ is anticipated but it could send a signal that they’re managing their differences

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

56

Preparations are in full swing for a summit between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden this month, but analysts say they do not expect any breakthroughs given the long-standing issues looming over the talks.

They say the much-anticipated meeting could, however, bode well for US-China ties and send a positive signal to regional countries that the world’s two biggest economies are managing their differences and trying to ease tensions.

The White House confirmed on Tuesday that the two leaders would meet in San Francisco later this month, with press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre saying Biden was expected to have a “tough … but important conversation” with the Chinese leader. Beijing has yet to confirm Xi’s attendance.

Advertisement

The US confirmation came after last week’s talks between China’s top diplomat Wang Yi and key officials in Washington including Secretary of State Antony Blinken and national security adviser Jake Sullivan. They had agreed to “make joint efforts to clinch a meeting” between the two heads of state.

The US will host the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco from November 11, and the American and Chinese presidents are expected to meet on the sidelines of the gathering. The Chinese foreign minister also met Biden during his three-day visit to Washington last week.

Advertisement

But according to a statement from China’s foreign ministry, Wang cautioned that “the road to the San Francisco summit will not be a smooth one”, and that the two countries “cannot rely on autopilot” for it to happen.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x