Chinese biotech scientists plan to use big data in war on cancer

Precision medicine a focus of latest five-year plan

When Nisa Leung was pregnant with her first child in 2012, her doctor in Hong Kong offered her a choice. She could take a prenatal test that would require inserting a needle into her uterus, or pay HK$1,000 more for an exam that would draw a little blood from her arm.

Leung opted for the simpler and less risky test, which analysed bits of the baby’s DNA that had made their way into her bloodstream. Leung then went on to do what she often does when she recognises a good product: look around for companies to invest in.

The managing partner at Qiming Venture Partners decided to put money into Chinese genetic testing firm Berry Genomics, which eventually entered into a partnership with the Hong Kong-based inventor of the blood test. Over the next few months, Berry is expected to be absorbed into a Chinese developer in a 4.3 billion yuan (HK$4.8 billion) reverse merger. And Leung’s venture capital firm would be the latest to benefit from a boom in so-called precision medicine, an emerging field that includes everything from genetic prenatal tests to customising treatments for cancer patients.

China has made the precision medicine field a focus of its 13th five-year plan, and its companies have been embarking on ambitious efforts to collect a vast trove of genetic and health data, researching how to identify cancer markers in blood, and launching consumer technologies that aim to tap potentially life-saving information. The push offers insight into China’s growing ambitions in science and biotechnology, areas where it has traditionally lagged developed nations like the United States.

“Investing in precision medicine is definitely the trend,’’ said Leung, who’s led investments in more than 60 Chinese health-care companies in the past decade. “As China eyes becoming a biotechnology powerhouse globally, this is an area we will venture into for sure and hopefully be at the forefront globally.’’

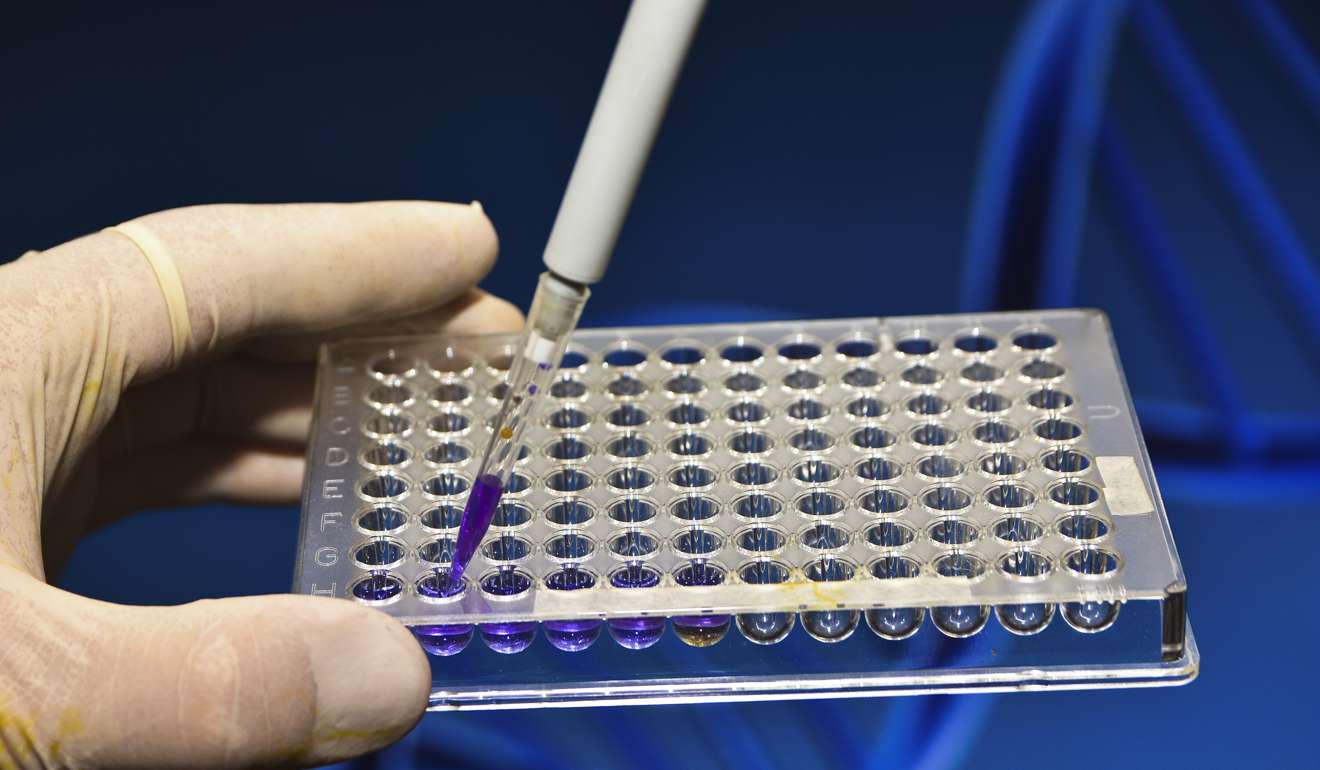

New Chinese firms like iCarbonX and WuXi NextCode that offer consumers ways to learn more about their bodies through clues from their genetic make up are gaining popularity. Chinese entrepreneurs and scientists are also aiming to dominate the market for complex new procedures like liquid biopsy tests, which would allow for cancer testing through key indicators in the blood.

Such research efforts are still in the early stages around the world. But doctors see a future beyond basic commercial applications, aiming instead for drugs and treatment plans tailored to a person’s unique genetic code and environmental exposure, such as diet and infections.

Professor Isaac Kohane, a bioinformatics expert at Harvard University, said that when it came to precision medicine, the science community had “Google maps envy”. Just as the search engine had transformed the notion of geography by adding restaurants, weather and other locators, more details on patients could give doctors a better picture on how to treat diseases.

For cancer patients, for example, precision medicine might allow oncologists to spot specific mutations in a tumour. For many people with rare ailments like muscle diseases or those that cause seizures, it allows for earlier diagnosis. Pregnant women, using the kind of tests that Leung used, could also learn more about the potential for a child to inherit a genetic disease.

The global interest in the field comes as the cost of sequencing DNA, or analysing genetic information, is falling sharply. But a number of hurdles remain. Relying on just genes is not enough, and there must also be background information on a patient’s lifestyle and medication history.

Precision medicine applications also require heavy investment to store large amounts of information. A whole genome is over 100 gigabytes, according to Edward Farmer, WuXi NextCode’s vice-president of communications and new ventures. “So you can imagine that analysing thousands or hundreds of thousands of genomes is a true big-data challenge.“

WuXi NextCode was formed after Shanghai-based contract research giant WuXi AppTec acquired a company called NextCode Health that has databases on the Icelandic population, which is relatively homogenous and therefore good for gene discovery.

In China, Wuxi NextCode now offers consumers genetic tests that cost between about 2,500 yuan (HK$2,800) and 8,000 yuan, providing more details on rare conditions a child might be suffering from or even the risk of passing on an inherited disease.

China is diverse and with almost 1.4 billion people, the planet’s most populous nation. WuXi NextCode announced a partnership with Huawei Technologies, China’s largest telecommunications equipment maker, in May to enable different institutions and researchers to store their data.

The goal is to use that deep pool of information – which ranges from genome sequences to treatment regimens – to find more clues on tackling diseases. WuXi said “this will in many instances enable the largest studies ever undertaken in many diseases”.

Another Chinese player, iCarbonX, which received a US$200 million investment from Tencent and other investors in April, is valued at more than US$1 billion. It announced last month that it had invested US$400 million in several health data companies to enable the use of algorithms to analyse reams of genomic, physiological and behavioural data to provide customised medical advice directly to consumers through an app.

The global precision medicine market was estimated to be worth US$56 billion in revenue last year, with China holding about 4 per cent to 8 percent of the global market, according to a December report from Persistence Market Research.

Encouraging interventions for some patients too early, even before they had life-threatening diseases, carried risks and came with ethical questions, Laura Nelson Carney, an analyst at Sanford C Bernstein, wrote in a note last month. Still, precision medicine research had many benefits, and some in China saw the country’s push as a significant opportunity “to scientifically leapfrog the West”, she said.

In the US, universities, the National Institutes of Health and American drugmakers are part of a broad march into precision medicine.

Amgen bought Icelandic biotechnology company DeCode Genetics for US$415 million in 2012, to acquire its massive database on Iceland’s population. US-based Genentech is collaborating with Silicon Valley startup 23andMe to study the genetic underpinnings of Parkinson’s disease.

“Humans are computable,” said Wang Jun, the chief executive of China’s iCarbonX. ”So we need a computable model that we can use to intervene and change people’s status, that’s the whole point.’’