What’s a ‘black swan’ and when will it strike next? China’s not taking any chances

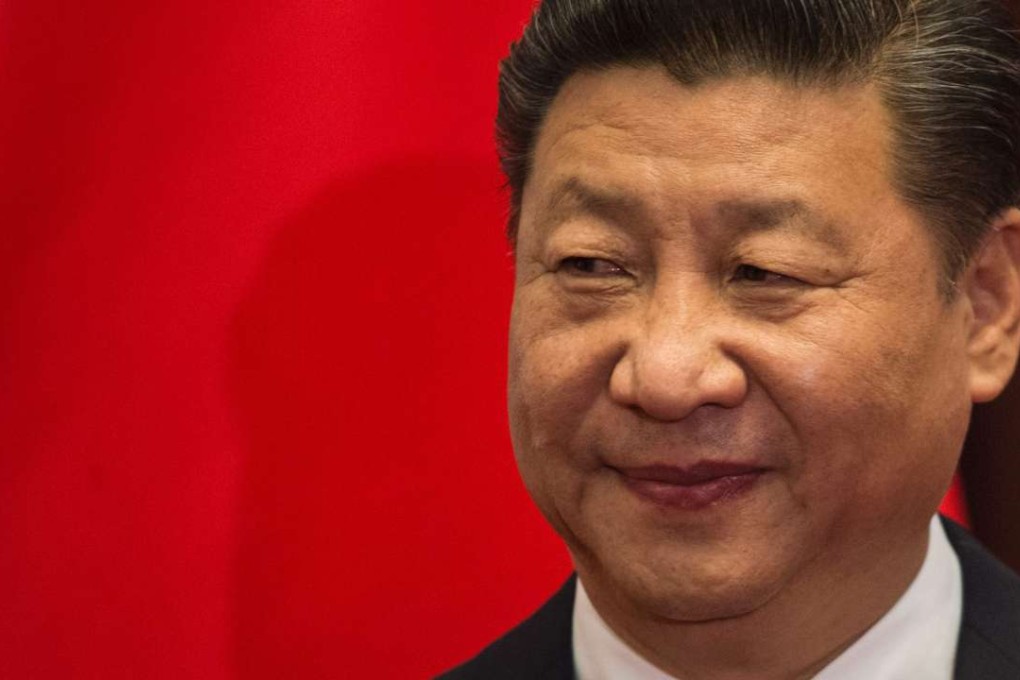

There was a financial crisis in Southeast Asia in 1997, another in the United States in 2007, so if a crisis comes this year where will it happen? This was the question posed during a speech last month by Yang Weimin, the deputy director of a finance and economics office serving President Xi Jinping.

“It certainly won’t happen at the South Pole or the North Pole,” Yang quipped.

“Only penguins live at the South Pole, but Black Swans live among us,” he said, referring to the term for unexpected events that can have far-reaching consequences on politics and the markets.

Yang’s warning came as China has launched a sweeping campaign to rein in risks deemed to pose a threat to the nation’s economy.

After the plunge in share prices during a stock market rout two years ago, plus the shock caused by Britain’s decision to leave the EU and the election of US President Donald Trump, the Chinese leadership is trying to avoid surprises in the coming months by whipping up the whole state apparatus to root out sources of instability ahead of a major Communist Party reshuffle in the autumn.