Beijing watches out for ‘grey rhino’ and ‘black swan’ in the jungle of financial risks

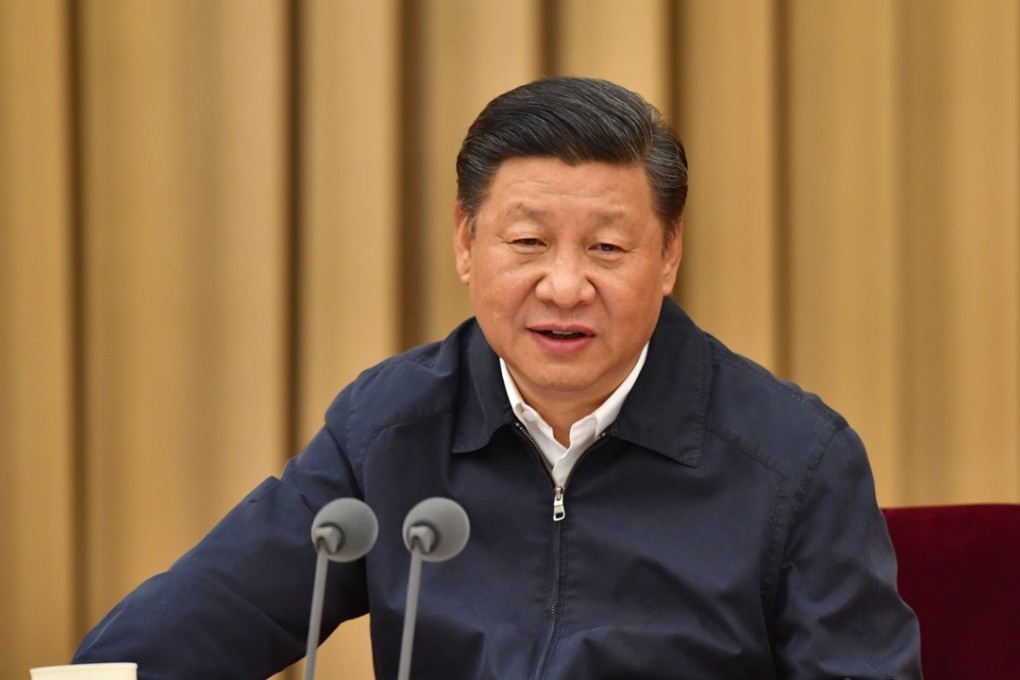

The Communist Party’s top mouthpiece invoked animal-inspired metaphors for risk in an editorial after the financial work conference wrapped up

Beijing is on guard against threats from a veritable jungle of financial risks – from the unpredictable “black swan” to the predictable “grey rhino”, the People’s Daily said in an editorial.

The terms slipped into the lexicon of the Communist Party’s mouthpiece on Monday, two days after China’s top leaders and policy makers wrapped up a significant financial work conference that is held every five years in Beijing. The gathering sets the agenda for actions to control risk across China’s fragmentally regulated financial system, from ballooning debt to expanding shadow banking.

“[We] need to prevent both ‘black swans’ and ‘grey rhinos,’” the People’s Daily said in its editorial. “We cannot play down or ignore small signs of any types of risks.”

The phrase “grey rhino” was coined by Michele Wucker, author of the 2016 book, The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore. The term refers to big and neglected dangers, such as the 2008 financial crisis which was preceded by a few early warning signs. A grey rhino is predictable compared with the highly unexpected “black swan”, another popular term used to categorise risk penned by Lebanese American trader-turned-writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb in 2007.

The fact that the Chinese Communist Party policymakers are abandoning quotes from Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong to adopt phrases from Western bestselling authors shows Beijing is trying to catch up or even lead market narratives, analysts said. The Chinese version of Wucker’s “Grey Rhino” book was published in February.