War of words breaks out over China’s economy as Xi readies for second term

Beijing tries to restore confidence in growth after another downgrade to its credit rating

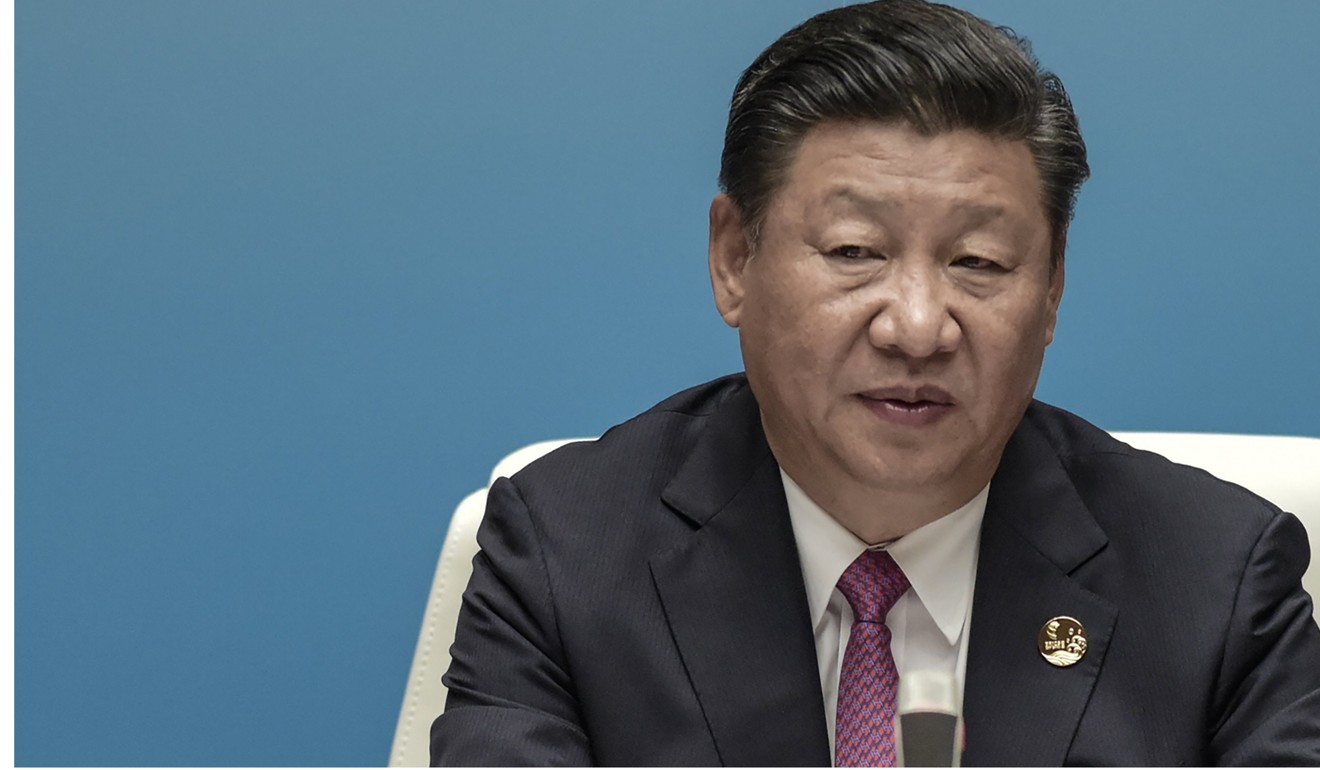

A war of words has broken out between Beijing and a rating agency over the state of China’s economy, just a month before the important party congress at which President Xi Jinping will consolidate his power.

On one side is S&P Global Ratings, the US agency that assesses the credit worthiness of 125 countries around the world, with a history going back to 1860.

It downgraded China’s sovereign credit rating from AA-minus to A-plus on Thursday – the first time it had done so since 1999 – saying the move reflected increased economic and financial risks in China after “a prolonged period of strong credit growth”.

On the other side is the Chinese government, which disagrees with S&P’s assessment. The finance ministry said in a statement on Friday that the downgrade by S&P was a “wrong decision” as the rating agency was ignorant of China’s sound economic fundamentals.

The issues in question – whether credit growth should be a concern for the world’s second biggest economy, and whether Beijing can defuse the debt bomb without causing any major economic fallout – matter a lot for China and the world.

Shen Jianguang, chief economist of Mizuho Securities Asia in Hong Kong, said the debt issue had been a focal point of economic debate since 2009, when debt ballooned after a flood of bank credit.

But Shen said it was wrong to overplay the impact of debt on China’s economic growth.

“There are elements of a credit-fuelled growth model in property and infrastructure development ... but there are also new economic drivers developing,” he said.

Debt accumulation has slowed since the Chinese leadership listed deleveraging as an economic priority in 2015 – but the overall debt level in the economy continues to rise.

“This is a steady, gradual deterioration in the risk profile of China,” Louis Kuijs, head of Asia Economics at Oxford Economics in Hong Kong, said after S&P made the announcement on Thursday.

Kuijs, who has previously worked for the World Bank, said China’s deleveraging efforts so far were restricted to the financial system and “there is no deleveraging” if it is measured by credit flows into the overall economy.

Mark Williams, chief Asia economist with Capital Economics, wrote in a note on Thursday that S&P’s downgrade timing “is awkward for China’s leaders, immediately ahead of next month’s party congress”.

While the downgrade “won’t be news to anyone who has kept half an eye on China over recent years and shouldn’t change anyone’s thinking”, Williams noted that it served as a reminder that “state sector reforms have continued to disappoint and so the hidden risks on bank balance sheets have continued to build”.

The Chinese government is seeking to paint a rosy picture of the economy after the dark days of late 2015 and early 2016, when it was seen as a source of risk globally following missteps by Beijing in managing a stock market rout and currency devaluation.

In 2017, it has set about restoring confidence in growth, with dozens of investment banks raising their forecasts for the Chinese economy.

Headline growth had a strong reading of 6.9 per cent in the first half, while foreign exchange reserves rose for a seventh month in August. The central bank meanwhile deliberately encouraged yuan depreciation after the Chinese currency gained nearly 7 per cent against the US dollar.

Last week, Premier Li Keqiang assured the heads of six international organisations – including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – that China’s economy had improved and its debt situation was “under control”.

So, after S&P cut China’s rating, the finance ministry said the decision was “perplexing”.

“S&P’s focus on credit and debt growth is largely old talk,” the ministry said. “It’s a pity that international rating agencies have been misreading the Chinese economy with their old mindsets and experiences gained from developed economies.”

The ministry made similar comments when Moody’s downgraded China’s sovereign rating in May – the first time it had done so since 1989.

But China has been unable to dispel doubts about its long-term economic health.

“The prolonged period of credit growth, in our view, has contributed to the weakening of liquidity ... that policymakers in China have enjoyed when they respond to shocks of any kind, and it also lessens medium-term financial stability,” Kim Eng Tan, senior director of sovereign ratings at S&P, told a conference call on Friday.

China’s stock market, the yuan exchange rate and bond prices were largely indifferent to the S&P downgrade on Friday. The reaction was similarly calm in May after the Moody’s downgrade.

In past decades, the Chinese government has been on the winning side of debates over the country’s economic trajectory, and doomsday forecasts about its growth model have so far failed to materialise – the ruling Communist Party has maintained its grip, there has been no “Minsky moment”, when the crisis hits and investors take flight, and no economic “hard landing”.

Additional reporting by Sidney Leng