Idle and abandoned: the hidden truth of China’s economic ambitions

Block after block of empty buildings in city that was poster child for China’s economic miracle show what happens when ambitious local plans meet economic reality. But can China wean itself off ambitious growth targets?

Business is slow in Tianjin’s Binhai New Area, says taxi driver Yang Xiang, with visitors claiming tax perks the most reliable sources of fares.

The southern part of the free-trade zone, including an area once touted as China’s “new Manhattan”, is block after block of mostly empty commercial buildings. Roads in the northern part, which is crowded with high-rise flats, are congested during rush hours but empty at other times.

It’s an object lesson in the perils of distorted development priorities – and the kind of thing President Xi Jinping is seeking to avoid in his quest for a more balanced Chinese economic growth model.

Yang, 28, said cabbies around Binhai’s Yujiapu financial district found it best to focus on the local railway station, where streams of people from neighbouring cities such as Beijing arrived every day before heading to local tax bureaus. They did not stay for long.

“An hour or two later, they have their tax affairs settled and begin their journey back to the railway station,” he said.

More than 20,000 companies are registered in Binhai, where preferential tax arrangements can halve a company’s tax bill. But even though there are also other incentives on offer, such as subsidies reducing rents by a third, much of their economic activity takes place elsewhere.

Binhai, encompassing 2,000 sq km of land around Tianjin’s port, was designated a “pilot area of comprehensive financial reform and innovation” in 2009. It once claimed its gross domestic product (GDP) had quintupled to 1 trillion yuan (US$145 billion) in the decade through 2016 and that it was China’s richest district, supplanting Pudong in Shanghai.

But the mirage did not last, with the Binhai authorities slashing its 2016 GDP by a third last month, to 666.4 billion yuan, after eliminating the double counting of business conducted elsewhere.

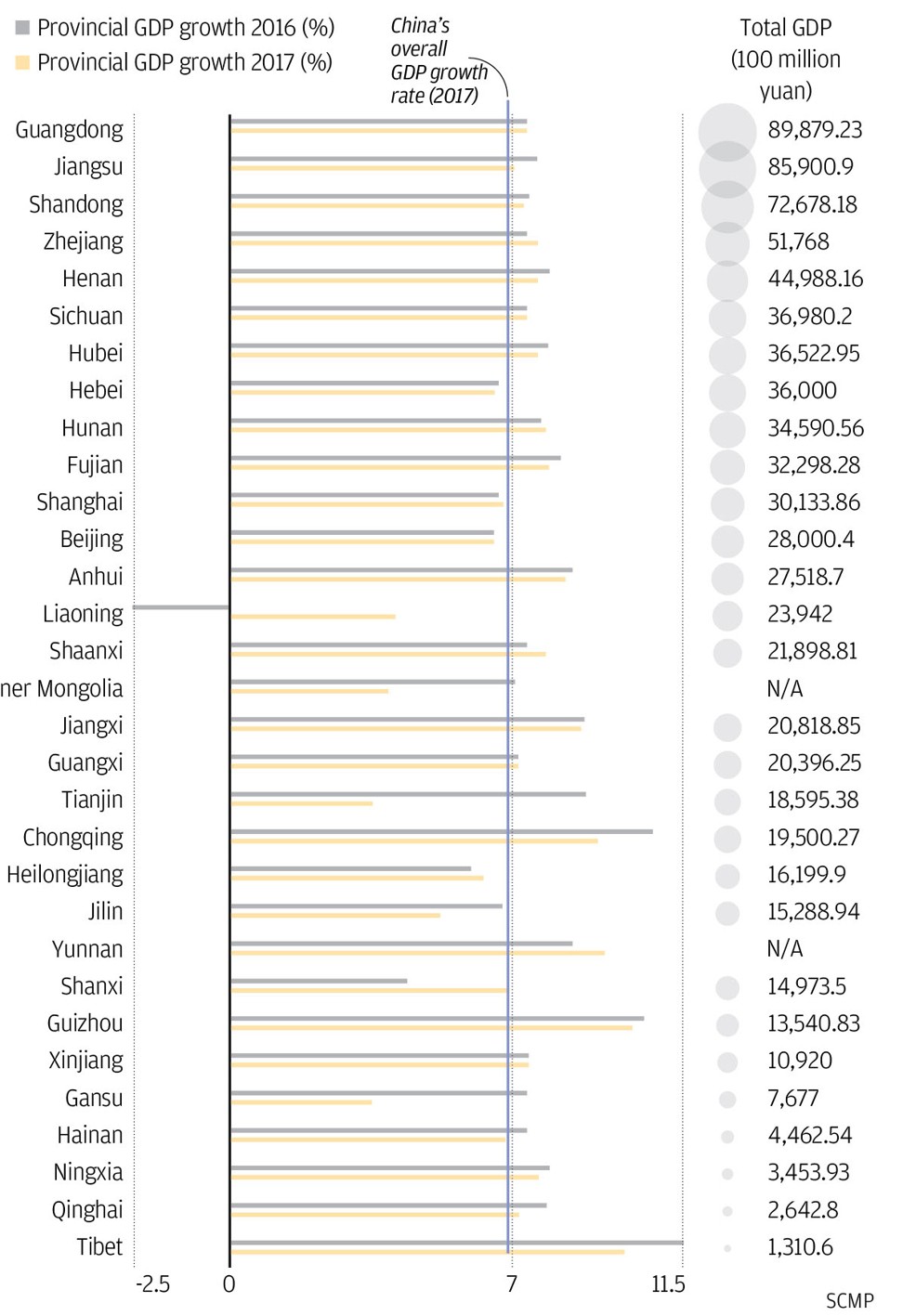

And Binhai was not alone in inflating its economic data. Inner Mongolia’s government said in November that about 40 per cent of the region’s reported industrial output in 2016, as well as 26 per cent of reported fiscal revenues, was fictitious.

China’s rust-belt province of Liaoning, meanwhile, admitted last year that local GDP numbers from 2011 to 2014 had been exaggerated by about 20 per cent.

But it was the confession in Binhai, a poster child of China’s investment-driven economic miracle, that raised the most eyebrows and generated the most debate about whether local governments would heed Xi’s call to pursue high-quality growth following decades chasing rapid expansion.

How the central government is progressing in weaning itself off growth targets will become more apparent next month when Premier Li Keqiang delivers his work report at the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s legislature.

Louis Kuijs, head of Asia economics at Oxford Economics, said the incentives had changed for provincial-level governments.

“There is more scrutiny by Beijing on ‘improper’ behaviour by local governments, including in areas such as local financing, corruption and ‘fake data’,” he said.

“Amid the move ‘away from quantity towards quality and equality’, economic targets such as on GDP, investment and fiscal revenues are becoming less important. Overall, this seems to spur local governments into coming clean in terms of the performance on growth and revenues.”

After consolidating his power at the ruling Communist Party’s national congress in October, Xi rolled out a plan for China’s high-quality development through 2050.

GDP growth is widely expected to be given less emphasis in officials’ appraisals, with more weight given to environment protection, poverty alleviation and other livelihood indicators.

While Li would announce a GDP growth target for this year at the NPC meeting, government sources said the general trend was for a de-emphasising of GDP growth targets in coming years. This year’s growth target – with many economists predicting around 6.5 per cent – would be used to ensure employment opportunities, sources said, but in the longer term there would be more emphasis on efficiency, fairness and the environment.

Tianjin’s government did not adjust the municipal GDP figure for 2016 after Binhai’s dramatic revision, saying its statisticians had never included the problematic part of Binhai’s economy in their calculations. The authorities had earlier said that Binhai accounted for more than half of Tianjin’s GDP.

However, after a revamp of its statistical practices, the Tianjin government reported GDP growth of just 3.6 per cent for last year, down from 9 per cent in 2016 and 17.4 per cent in 2010, during a run of double-digit annual growth stretching back to 1999.

Echoing the new “slower is better” mantra, Tianjin party secretary Li Hongzhong told local officials at a meeting in January: “We must get rid of the speed complex. We must break away from the outdated development concept … and be determined to push ahead with high quality development.”

Binhai started developing the Yujiapu financial district more than a decade ago, with the authorities pledging more than 200 billion yuan in investment, but in recent years it has made international headlines as a spectacular ghost town.

Envisioned as Tianjin’s answer to Manhattan, it rose from a riverside wetland. But on a recent weekday morning, only a handful of people, in thick down jackets, could be seen on its streets. Some finished buildings are partly occupied but others remain under construction or look abandoned.

Liu Jinming, a retired primary school teacher, was walking along the river bank with his grandson. Pointing to the Yujiapu skyline, he said: “Lights can only be seen from a very small number of windows at night. It’s scary.

“I haven’t seen any improvement over the past few years. Some government departments have been relocated here. But that’s all.

“Businessmen are not interested in moving move here. It was the wrong decision to set up a financial district here.”

Tianjin, a northern industrial base, missed one chance to develop into a major financial centre in 2007, when a pilot scheme to allow mainland Chinese residents to directly invest in Hong Kong stocks via Binhai was aborted due to concerns about capital flight.

A high-speed rail link to Beijing has been built since then, but it failed to boost business prospects.

In search of a new niche, Binhai was declared a free-trade zone in 2015, offering consumers everything from Italian Maserati cars and Japanese napkins at slightly reduced prices.

But at the Global Go shopping centre in Yujiapu, customers are rare, even at lunchtime. A vintage car exhibition in the mall was hoping to charge visitors 58 yuan for a closer look at cars ranging from a 1940 Willys Jeep to a 1970 Ferrari coupe, but due to the lack of demand staff now allow admission free of charge.

One staff member said the exhibition had been put on by the local government.

“But we don’t call it a government-organised event,” he said. “Nowadays, we do things under the name of a company. You know, corporate activities are most needed here.”

Binhai’s 38 sq km central business district, which covers Yujiapu on one side of the Hai River and Conch Bay on the other, was the most aggressive part of the new area in pursuing headline growth. Binhai, in turn, was promoted as the driver of development in Tianjin, a municipality of 15.6 million people which dreamed of becoming China’s “third growth engine”, following Shenzhen in the 1980s and Pudong in Shanghai in the 1990s.

In pursuit of that dream it followed a common path of regional economic development in China: designating a development zone, pouring government funding and bank loans into it, and then, after negotiations with the central government, offering tax breaks, cheap land and subsidies to woo investors.

Macquarie Capital economist Larry Hu said local governments still favoured high GDP figures.

“However, they cannot overdo it, otherwise fiscal transfers and other support from the central government might decline,” Hu said. “An adjustment of past figures could highlight the predicaments of local coffers and facilitate central government support.”

Tianjin’s government is the mainland’s most heavily indebted city government, with the debts of its local state-owned enterprises (SOEs) amounting to 700 per cent of local fiscal income in September, according to a report by the credit rating agency Moody’s last year.

Other provincial-level areas that were heavily indebted included Chongqing, Shanxi and Yunnan, where the ratio stood at between 400 and 600 per cent.

Moody’s has cautioned that the outlook for Chinese local governments is negative this year, with the indebtedness of their SOEs expected to remain high.

Shen Jianguang, an economist with Mizuho Securities, said high leverage – linked to the massive investment projects that were local governments’ main approach to economic growth in past decades – was the biggest risk to the Chinese economy.

“It is possible that local officials want to create a lower comparable base, so they adjusted past GDP figures lower to make future growth look better,” he said. “That said, we cannot rule out that some local governments really want to embrace high-quality growth.”

Ricard Torne, head of economic research at FocusEconomics in Spain, said data for last year was showing the Chinese economy was transitioning from an economic model based on investment and manufacturing towards one dependent on consumption and services, with nominal fixed-asset investment falling to multiyear lows and nominal retail sales remaining robust.

However, even though the National Bureau of Statistics would launch its own survey and investigation on local economies from next year, it was too early to say that local data manipulation would end.

“It would be an arduous task [to stop data manipulation], especially at the regional level, which has been the best way to be promoted within state and party structures,” he said.