Analysis | Too little, too late? Foreign bankers fall out of love with China as Beijing fails to open up

Overseas investors in the financial sector are weighing their options amid tougher competition, political uncertainty and an unfriendly regulatory environment

Roughly two decades ago China made a momentous decision to win the hearts of global capitalists and gain entry to the world’s biggest club of trading nations.

It promised to deregulate its financial sector and open its banking market to foreign players.

Seventeen years down the track, some rule changes have been made but foreign players are still at the margins, battling regulatory foot-dragging and greater domestic competition.

Banking is a litmus test for the broader Chinese economy. For decades, Beijing took it for granted that overseas investors would be waiting at the gates, keen for a share of a massive market.

But that investment tide could be turning as Beijing tightens its grip on economic activity and its piecemeal deregulation raises doubts about its commitment to free trade.

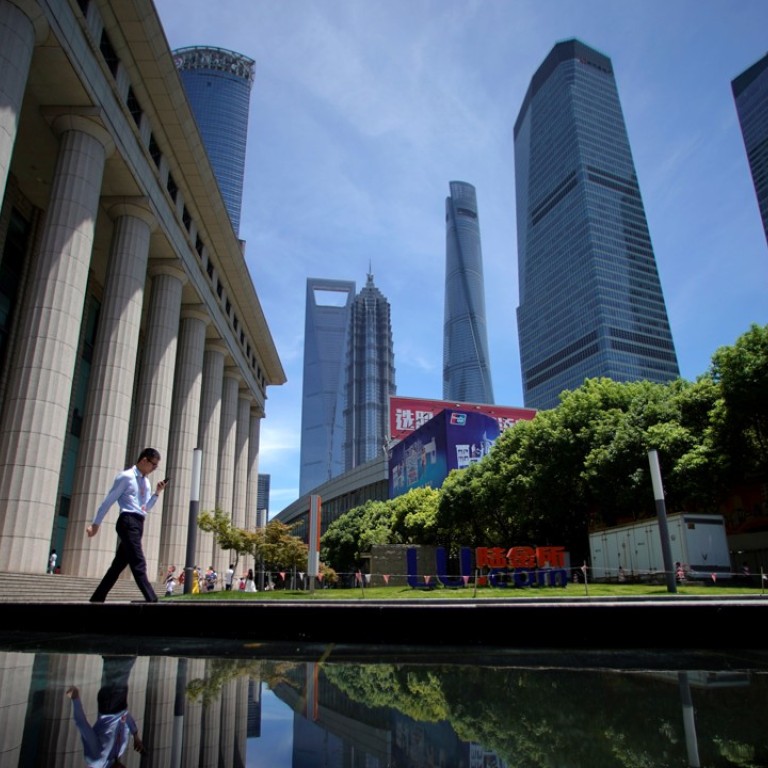

China’s financial sector has ballooned from a near standing start at the turn of the century. The country’s state banks, once technically bankrupt, are now the world’s biggest and most profitable lenders.

Protected from foreign competition and by a closed capital account, the sector’s assets grew by a factor of 12 between 2001 and 2016 to total more than 224 trillion yuan (US$35.3 trillion).

The total assets of foreign banks in China also grew – increasing at an average rate of over 20 per cent a year from 92.79 billion yuan in 2006 to 2.68 trillion yuan in 2015.

But the foreign banks’ share of the overall holdings more than halved from 2.38 per cent in 2007 to 1.38 per cent in 2015, according to China’s official statistics.

The central government has taken some steps to ease the way for overseas players. Just last week, the country’s banking watchdog said foreign lenders only had to apply for one, instead of two, regulatory approvals in opening a new branch. It also said it would scrap administrative “pre-approvals” for banks to offer offshore wealth management services to clients or act as custodians for mutual funds investing in stock markets as long as they notified the regulator.

It is the kind of action that foreign lenders have long called for but bank executives say it could be too little, too late.

“There have been many discussions about the prospects of China’s financial sector among peers in foreign banks recently,” one foreign banking source in Beijing said. “The regulatory easing is a positive move, but many of us are more worried about the prospects of China’s financial sector.”

Another source involved in deciding China strategy for an American bank said conditions now made it difficult to assess the political risk of expanding in China.

“Actually we’ve been more keenly looking into opportunities in India since 2012, as we find it harder to discern China’s politics and foresee its policy direction,” the source said.

Foreign bankers are wondering about the potential fallout from Chinese President Xi Jinping’s decision to make curbing financial risks a top priority and the flood of investigations into officials and businesspeople suspected of disrupting market order.

Beijing is also moving to eliminate constitutional term limits for the presidency.

Guo Tianyong, from the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, said foreign investors were probably less interested in China than a decade ago because they knew it was tougher to make easy gains.

“Foreign banks are struggling in China even with a friendlier regulatory environment because mainland commercial banks have become very competitive,” Guo said.

“It will take some time for foreign investors to regain an understanding of China’s banking sector and economy in general, as dynamics have changed a lot [in the last 10 years].”

Some foreign banks were forced to cut back on operations in China during the global financial crisis while others missed the opportunity ride the Chinese wave of expansion and innovation such as mobile banking and internet financing, according to a KPMG report.

Conditions now are clouded by the prospect of a trade war between China and the United States.

A month after Liu He, Xi’s top economic aide, told the world’s rich and powerful at the Swiss ski resort of Davos that China would open its domestic markets wider and that this year’s reform measures could “exceed the international community’s expectations”, he was in Washington last week on an urgent mission to defuse trade tensions. Little appears to have come out of the trip except for an agreement to keep talking.

Brock Silvers, managing director of Kaiyuan Capital, a Shanghai-based investment advisory firm, said a cocktail of factors, including uncertain China-US ties, concerns about intrusive state intervention and perceived political risks, would deter foreign investors from China.

There was no sign of a convertible yuan or an end to capital account controls, major concerns for financial investors, he said.

“[And] China’s political risk, or at least Western perception of it, seems to be increasing,” Silvers said.