Has China found a trade war loophole? Officials tout ‘made in Vietnam’ zones on border amid US tensions

Bonded areas could provide shelter for manufacturers hit by US tariffs – if China can convince its southern neighbour to get the plan moving

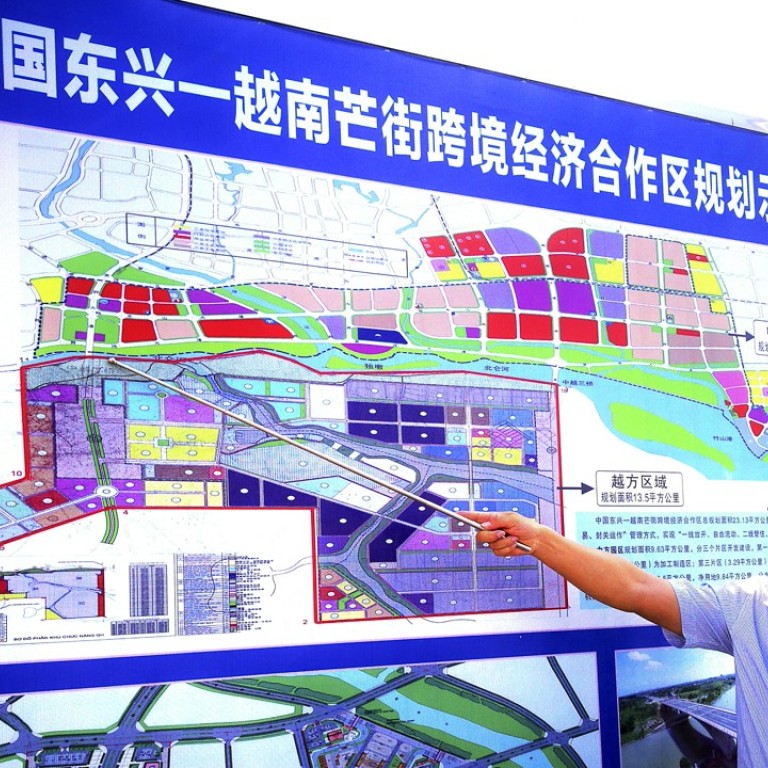

A spiralling trade conflict between Beijing and Washington is an unwelcome development for China, but officials in Guangxi – where seven “cross-border trade zones” with Vietnam are planned – see an opportunity.

The border has sheltered Vietnamese nationalists trying to overthrow the French in the 1930s, and Ho Chi Minh’s guerilla soldiers fighting the US army in the ’60s. Parts of the 1,300km frontier became battlefields in a brief yet bloody war between China and Vietnam in 1979. Four decades on, it could be about to play a role in a very different kind of war.

Washington and Beijing on Friday fired the opening shots in a trade row that looks set to escalate, slapping 25 per cent tariffs on US$34 billion of each other’s goods.

Exporters in China’s manufacturing heartland brace for impact of US tariffs

In the Guangxi region, home to museums dedicated to late Vietnamese communist leader Ho, officials are now touting with renewed vigour the idea of the cross-border zones, where exporters from China could assemble products and label them as “made in Vietnam”.

The bonded zones are part of a wider cooperation plan signed by Beijing and Hanoi last year, under China’s belt and road trade and infrastructure strategy. If they go ahead, they could provide shelter for manufacturers hit by US President Donald Trump’s tariffs.

One of the zones is in the border town of Pingxiang, administered by the city of Chongzuo. The city’s deputy mayor, Lu Hui, said they wanted to create a cooperation zone with Vietnam that had “a free flow of workers, capital and materials”.

Lu, promoting the plan to media on a government-organised tour, said products made in the zone could be labelled either as “originating in Vietnam” or “originating in China”.

Wang Fanghong, the Communist Party boss of Pingxiang, also said the dispute with Washington could give the trade zones plan a boost. It “could be a chance” for his small town to speed up development, Wang said.

Exporters trying to ship products made in China “will find it difficult to send them to the US directly, and some will be transported via Asean members”, he said.

Wang suggested places on the border with Vietnam like Pingxiang could go the extra mile and turn this “transfer trade” into “local processing and manufacturing”.

Officials trying to sell the plan to export-oriented businesses in the country’s manufacturing heartland, Guangdong province, and the Yangtze River Delta say it will give them access to cheap labour from Vietnam and a wide range of preferential policies offered by both sides of the border.

Those policies, according to the promotional materials for the zones plan, would reduce logistics, staffing and tax costs.

China and Vietnam close to landmark deal on streamlined joint border checkpoint

Significant savings could be made on wages, according to the Chinese officials, who said local manufacturing workers were paid about a third of the salary of those in the Pearl River Delta.

Factory workers in Shenzhen and Guangdong are paid an average wage of 5,000 yuan a month (US$750), compared to a daily average of 80 to 100 yuan (US$12 to US$15) earned by those in northern Vietnam. Factories in the cross-border zones would also be shielded from the regular threat of protests and strikes faced by Chinese businesses operating in Vietnam, the officials said.

Last month, demonstrators set fire to police vehicles, defaced government buildings and brought Chinese-owned factories to a standstill across Vietnam. It was the worst flare-up of anti-Chinese sentiment since 2014, as workers protested over the government’s plan to set up three new special economic zones where investors will be able to lease land for up to 99 years. Demonstrators fear they will be dominated by Chinese interests.

These zones are separate to the ones planned on the border with China, but this growing unease over the country’s powerful northern neighbour is one of many hurdles the Chinese officials will have to overcome. Another is convincing Beijing to give them greater autonomy in trade zones like the one in Pingxiang, under a “two countries, one free-trade zone” special administrative set-up.

‘Don’t give our land away’: the clash of interests in Vietnam’s anti-China protests

But convincing Hanoi to get the process moving could also prove challenging. A member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and a signatory to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, Vietnam has so far been cautious about the zones. While it has agreed to the plans, work on building the zones and necessary infrastructure is lagging.

The two sides still need to work out the details of the cooperation, according to Nguyen Anh Thu, vice rector of the University of Economics and Business at Vietnam National University in Hanoi, who studies the economics of cross-border zones.

“Even in very difficult political times with China, still we export to them. This is why there is a great need for officials from the neighbouring Chinese region of Guangxi and officials from Vietnam to sit down and talk more about how to cooperate, especially about trade and how it will benefit both sides,” Nguyen said.

“There is no clear model of cooperation [for the zones] – what is there is not very sustainable, and it’s difficult to see the benefit,” she said, referring to existing trade passing through the border areas.

At present, there is not much industrial capacity in those areas.

“There are inputs from China that come to Vietnam to be manufactured for export to the US market, but they have to come further from the border to Hanoi or other areas. The industrial zones in the border provinces are not yet well developed, but there is some hope for the future,” Nguyen said.

Meanwhile, Washington and Hanoi have launched a joint investigation into alleged cases of products being labelled as originating in Vietnam when they were actually produced in China, in order to avoid paying duties, according to a Vietnamese journalist who has been covering the issue.

Roger Chau also said there was opposition to the cross-border zones on the Vietnamese side.

“Many Vietnamese are concerned about the growing number of Chinese investments in the country. They see Chinese factories as bringing serious pollution, they worry about bribes and problems with the land,” Chau said.

Don’t just blame Trump or China for this trade war

The idea of creating border zones to facilitate trade is not new and the Chinese government supports other such zones shared with Myanmar, Laos, Russia and Kazakhstan – though its efforts to set up something similar with North Korea failed.

Under the deal with Vietnam, China will invest in and build infrastructure for the zones along the border – including facilities designed to speed up customs clearance and get cargo flowing through the checkpoints more easily. The facilities are expected to span 20 to 100 sq km on both sides of the border.

Guangxi Jingxi Full Rich Investment is one of the Chinese companies that has invested in the zones. Xiong Hongming, vice-president of the government-backed firm, said it had a budget of 3 billion yuan for the Longbang-Tra Linh zone. He said his company had already spent 1.9 billion yuan, largely on the Chinese side of the facility.

Xiong also acknowledged that one function of the zone would be to offer manufacturers the chance to “avoid Washington’s heavy tariffs on Chinese goods”.

But for now, Xiong’s most pressing task is to line up meetings with senior cadres on the other side of the border in Cao Bang province, to make sure they stay committed to the plan. He will start with the offer of 100 Chinese manufacturers setting up on the Vietnamese side of the zone, where their initial investment will allow construction to begin.

The demand is there for Chinese exporters seeking some sort of protection against Trump’s trade wrath, according to Liu Kaiming, who heads the Institute of Contemporary Observation in Shenzhen, an NGO monitoring the working conditions of Chinese manufacturers.

Liu added that the cross-border zones could be a good testing ground for export-oriented businesses wanting to ship through other countries, or even to relocate their operations elsewhere in the region.

“But the problem is, whether the Vietnamese government says yes,” he said.