China sets sights on new global export: nuclear energy

But analysts say multibillion-dollar plan ignores reality of weak global demand

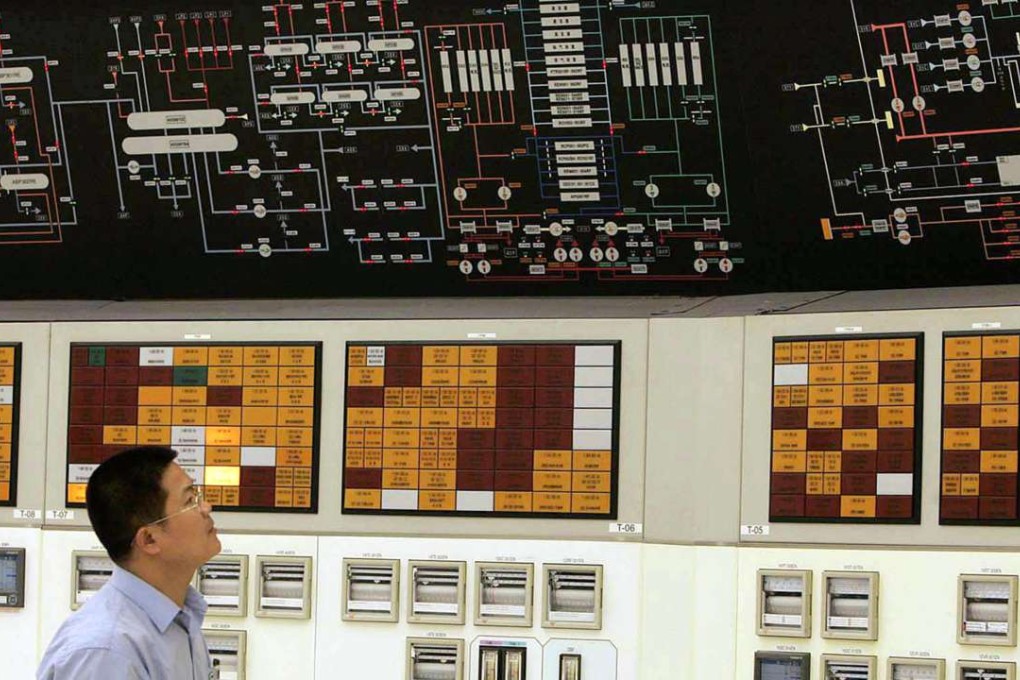

On a seaside field south of Shanghai, workers are constructing a nuclear reactor that is the flagship for Beijing’s ambition to compete with the United States, France and Russia as an exporter of atomic power technology.

The Hualong One, developed by two state-owned companies, is one multibillion-dollar facet of the Communist Party’s aspirations to transform China into a creator of profitable technology from mobile phones to genetics.

Still, experts say Beijing underestimates how tough it will be for its novice nuclear exporters to sell abroad. They face political hurdles, safety concerns and uncertain global demand following Japan’s Fukushima disaster.

China’s government-run nuclear industry is based on foreign technology, but has spent two decades developing its own with help from Westinghouse Electric, France’s Areva and EDF and other partners. A separate export initiative is based on an alliance between Westinghouse and a state-owned reactor developer.

The industry is growing fast, with 32 reactors in operation, 22 being built and more planned, according to the World Nuclear Association, an industry group. China accounted for eight of 10 reactors that started operation last year and six of eight construction starts.