How new Xinjiang party boss became front runner in race to be one of China’s most powerful men

Chen Quanguo’s hardline rule in Tibet and show of absolute loyalty to Xi Jinping may see him promoted to Politburo next year

The new Communist Party chief in Xinjiang, Chen Quanguo, is strongly tipped to join the party’s Politburo next year as a result of his strong ties with Premier Li Keqiang and five years of hardline rule in his previous post in Tibet, which won him the trust of party general secretary Xi Jinping.

Chen, 60, is well placed in the race for promotion to the decision-making Politburo because age has become a key criteria for political advancement and retirement.

Since 2002, the so-called “seven up and eight down” rule has allowed cadres who are 67 or younger at the time of a party congress to remain in or enter the Politburo, while those aged 68 or older have been pushed into retirement.

If the rule still holds and the number of Politburo seats remains at 25, 11 elderly Politburo members will have to step down at the party’s 19th national congress, which is scheduled to be held in autumn next year.

Chen, long viewed as a close ally of Li, will be a front runner for one of the vacancies thanks to his work experience and tough stance in dealing with religious and ethnic issues in Tibet.

He worked closely with Li for six years in Henan province, beginning with his appointment as Li’s deputy when Li was made acting governor of the central province in 1998. Then, in 2000, Chen was made a member of the party’s provincial standing committee.

In 2003, a year after Li was promoted to Henan party secretary, Chen became his deputy in the party’s provincial committee.

After serving as deputy party chief of Henan for 6½ years, Chen was promoted to acting governor of the neighbouring province of Hebei in late 2009, when he was 54. Then, in 2011, after 18 months as Hebei’s acting governor and governor, he was named party head of Tibet.

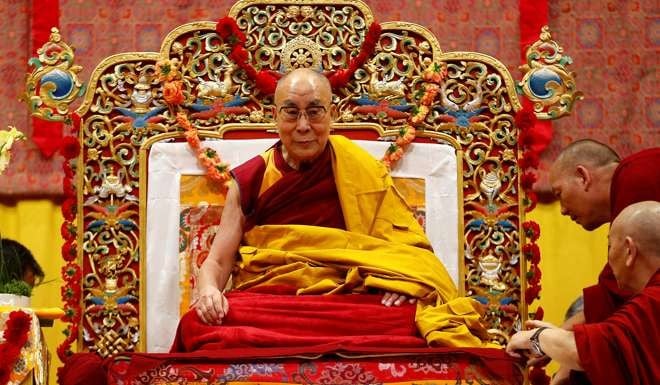

In his first meeting with senior cadres in the autonomous region, Chen promised the authorities would bar the “Dalai clique” from intervening in the selection of the next Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader. Buddhists in Tibet believe that each Dalai Lama is the reincarnation of his predecessor.

Beijing views the current Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in Dharamsala, India, after fleeing Tibet in 1959, as a separatist, and Chen told the cadres the battle against his clique would be long-lasting and intense.

Whenever Chen visited schools in the region or penned articles for the party magazine he underscored the importance of “feeling the party’s benevolence, listening to the party’s words and following the party’s path”, while also urging people to distance themselves from the Dalai Lama.

Chen served as the top party official in Tibet for almost five years and in the eyes of top leadership in Beijing one of his key merits in that time was his role in the purging and punishment of officials deemed to be hidden supporters of the Dalai Lama. State media reports said that in 2014 at least 15 regional officials were found to have participated in the illegal, underground Tibetan independence movement, provided intelligence to the Dalai clique or otherwise assisted activities that posed a threat to national security.

Chen’s hardline policies in Tibet appear to have won him Xi’s trust and confidence. At the party Central Committee’s Sixth Tibet Work Forum in August last year, Xi stressed that political correctness was the overriding priority in the appointment of officials, saying that anybody with split loyalties had to be eliminated from the ranks of party officials and members.

Apart from resolutely toeing the party line, Chen has also pulled out all stops to show his loyalty to Xi and was among the 20 or so regional party secretaries who early this year publicly supported the characterisation of Xi as the “core” of the party leadership.

At the annual meeting of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in Beijing in March, each delegate from Tibet wore two badges: one featuring Xi and his four predecessors – Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao – and the other featuring Xi alone.

Pundits interpreted it as a successful political show choreographed by Chen to explicitly convey his allegiance to Xi.

Chen’s heavy-handed rule in Tibet and his loyalty to the party’s top leader was rewarded in August with his transfer to Xinjiang as party secretary, replacing Zhang Chunxian who had been criticised for using “soft tactics” in ruling the restive northwestern region.

As the only current regional party chief to have played leading roles in four separate provinces and regions – Henan, Hebei, Tibet and Xinjiang – Chen has a clear advantage over other Politburo contenders.

Bo Zhiyue, a professor of Chinese politics at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, said Chen’s appointment as party boss of Xinjiang had sent out a clear signal that he was destined for promotion to the Politburo at next year’s party congress.

“Judging by Chen’s work experience, he is relatively closer to Li,” Bo said. “But this doesn’t mean that he boasts no ties with Xi.”