Will China’s ‘core’ leader Xi Jinping now turn attention to economic reform?

Analysts keen to find out whether Communist Party chief is a hardliner or reformist

A big question mark hanging over the future of the Chinese economy will soon be cleared up: is Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping an old-style hardliner who views absolute power as an end in itself or a reformist who sees the consolidation of power as a necessary step towards meaningful reform?

The risk is that a regime with highly concentrated power is prone to make policy choices which are incorrect

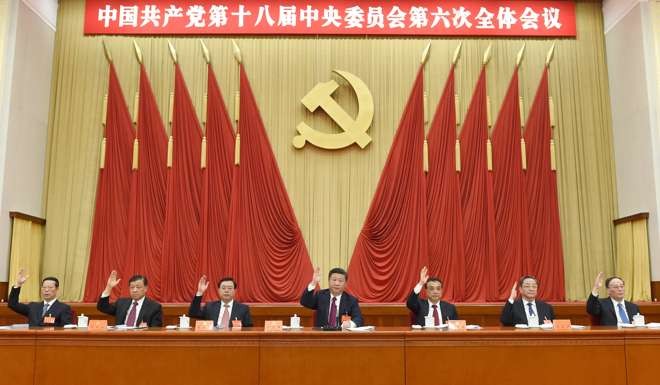

With a key party meeting last week recognising Xi as the “core” of the party leadership – acknowledgement of his undisputed authority – fingers are once again crossed that he will use his status as China’s most powerful leader in decades to kick-start much-delayed economic liberalisation, with reforms targeting areas ranging from the fiscal system to land ownership.

Since becoming party chief four years ago, Xi has promised a long list of “supply-side structural reforms” for the world’s second-biggest economy, including defusing a debt bomb, reducing pollution and phasing out obsolete industrial facilities. But China’s economic imbalances have worsened on his watch, with rising levels of debt, persistent pollution and property price bubbles emerging in major cities.

One theory is that vested interests – ministries, local authorities and state-owned enterprises – have been hindering Beijing’s reform ambitions and that Xi will be able to use the boost to his authority to smash through that resistance.

Liaoning, the only Chinese province to report economic contraction in the first half of this year, was also the scene of a massive vote-rigging scandal in the local legislature, while Hebei, the steel-producing province surrounding Beijing, only half-heartedly followed Xi’s instructions under former provincial party boss Zhou Benshun, who has been expelled from the party and is awaiting trial on graft charges.

Deng Maosheng, a government researcher who participated in the drafting the communique issued by the party Central Committee’s sixth plenum last week, told a press briefing in Beijing on Monday that Xi’s new status in the party “will become a strong force to drive reforms”.

“The intensified central power will no doubt help the enforcement of policies and reforms,” Deng said.

Tim Condon, head of Asian research at ING in Singapore, concurs. “The elevation of President Xi is expected to enable him to overcome resistance to the supply side structural reform agenda,” he said.

While fighting corruption has become a hallmark of Xi’s rule in the past four years, key economic reforms have been slow to emerge. Rural land ownership reform, which would give farmers greater say over their land, has stalled, hindering China’s urbanisation drive. Fiscal revenue reform has been limited, with local governments still relying on land sales deals for income. And the pledge to break up state-owned monopolies appears to have gone into reverse.

That’s all prompted growing suspicion about China’s liberalisation trajectory and raised doubts about whether an authoritarian regime under a strongman ruler will ever be truly willing to give up control over economic matters.

Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research, said Xi was “fighting a rearguard battle against princelings and other forces in China in his bid to restructure ailing state firms and make the economy more efficient”.

“Xi’s new title as a ‘core’ leader strengthens his hand against those contesting his economic restructuring plans,” Collier said. “However, it’s not clear that even with his increasing power Xi will be able to resolve these knotty economic problems.”

Yuan Gangming, a Tsinghua University economist, said the “core” title was recognition of Xi’s power, and did not represent new empowerment. Xi already had enough power to push through necessary reforms because he headed various central leading groups governing everything from national security to “comprehensively deepening reforms”.

Yuan said Xi had “shown his muscle in fighting against corruption and achieved unimaginably remarkable results”.

“It should not be too hard for him to press ahead with the economic reforms, which are not ‘hard bones’ at all compared with the difficulty of the anti-corruption battle,” said Yuan, who used to work for the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. “However, the risk is that a regime with highly concentrated power is prone to make policy choices which are incorrect.”

Arthur Kroeber, an economist with Gavekal Dragonomics, said the direction of economic policy under Xi had been confusing, but two themes had been consistent: resistance to the occasional downturns that were intrinsic to well-functioning markets, and advocacy of a continued central role for the state.

“So far as we can tell, these are Xi’s own core views, not tactical stances taken because he lacks the authority to implement change,” Kroeber wrote in a research note.” Xi’s position seems to be that economic reform is fine, so long as it creates no volatility and no diminution in state control.”

Because of that, Kroeber said, “there are few signs that Xi is an economic reformer at heart”.

Yuan said that by being in a paramount position, with all the levers of power in his hand, Xi would have to bear direct responsibility if reforms failed or showed no progress.

“And the risk of little progress is high as the regime lacks a democratic decision-making and rectification mechanism,” he said.

Additional reporting by Zhuang Pinghui