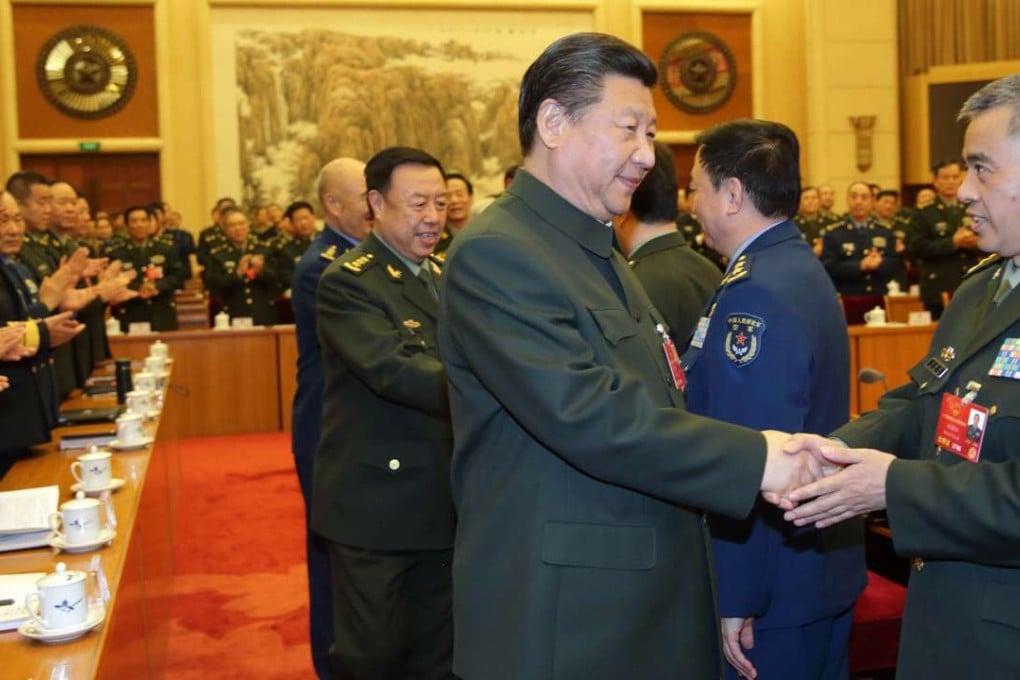

How did China’s Xi Jinping secure ‘core’ status in just four years?

Communist Party chief moved swiftly to assert his power early in his tenure, sweeping away resistance in the military command

How did the head of China’s Communist Party, Xi Jinping, come to be hailed as the “core of the party leadership” in less than four years when his predecessor, Hu Jintao, never achieved such recognition in 10 years as party chief?

Party general secretary Xi was given the “core” title for the first time in an official party document in the communique issued by the party Central Committee’s sixth plenum, which ended on October 27. It urged the party to unite around “the party’s centre with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core”.

Unlike the title general secretary, “core” is not defined in any official party documents available to the public, but analysts say the title gives Xi final veto power.

Many see his elevation as marking the end of the party’s decades-long effort to make the leadership more collective, with China watchers saying Xi’s anointment owes much to the absence of any protracted influence by Hu following his retirement as party chief in 2012.

Chen Daoyin, an associate professor at Shanghai University of Political Sciences and Law, said Xi had enjoyed much more favourable circumstances inside the party than his predecessors in terms of consolidating and centralising power.