Will Xi Jinping cut seats at Politburo top table from seven to five?

President may be able to consolidate grip if number of seats in Politburo Standing Committee is trimmed to five at next year’s five-yearly leadership shuffle

A question at a press conference three months before the Communist Party’s 18th national congress in 2012 caught a spokesman for the party’s Organisation Department off guard.

“How many people are there in the next Politburo Standing Committee?” an American journalist asked.

The spokesman for the department, which oversees the party’s apparatchiks, could only reply: “I don’t know.”

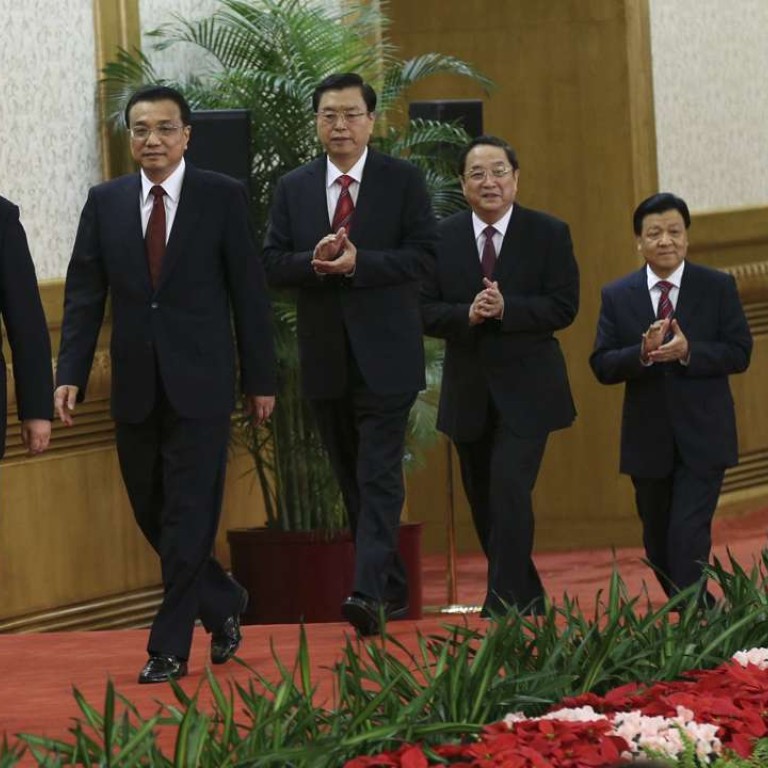

In fact, before the members of the new Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s top decision-making body, walked onto the stage at the conclusion of the five-yearly party meeting to pose for pictures, the world was as clueless about their identity as it was about their number.

Analysts said the five-yearly reshuffle at the top of the party looming late next year, centred around its 19th national congress, would present a good opportunity for party general secretary Xi Jinping to consolidate his power by reducing the Politburo Standing Committee membership from seven to five.

Fluctuations in the size of the Politburo Standing Committee are important because the numbers game can decide which faction has the upper hand at the pinnacle of power and thus significantly affect top-level decision making – even for Xi, who was anointed “the core” of the party’s leadership in October.

If there is no change to the size of Politburo Standing Committee or the retirement age for its members next year, five seats will be up for grabs, with all the incumbent members – except for President Xi and Premier Li Keqiang – having reached the unofficial retirement age of 68.

While the list of candidates for elevation to the Politburo Standing Committee is not released publicly, it is possible to narrow down the pool of contenders, based on the party’s top-level retirement rules and the claims of hundreds of officials of ministerial level or above, especially those with more convincing portfolios of work.

However, the size of the Politburo Standing Committee is more unpredictable, with the number of seats swinging between three and 11 since 1927, when it was first formed.

The Politburo Standing Committee has not always been the party’s supreme body. It was replaced by the Central Secretariat between 1934 and 1956 before making a comeback in the decade before the Cultural Revolution. Then it was sidelined for another decade from 1966 after then party leader Mao Zedong unleashed the Cultural Revolution, a destructive decade of political and social upheaval.

Technically, it only gained exclusive decision-making power in 1992, when then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping disbanded the Central Advisory Commission, a body comprised of influential, retired party elders, which previously had the final say on key decisions. But party elders still retain varying levels of non-institutional influence, depending on their personal power.

While moving the Politburo Standing Committee up or down in the party’s chain of command was possible under Mao and Deng, Ding Xueliang, a professor of Chinese politics at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said leaders since Deng could only content themselves with tinkering with its scale.

“In the early years, Mao had influence on decision making by bringing people from his camp to enlarged meetings,” Ding said. “Jiang [Zemin] did the same thing when he could not kick out people already in the Politburo Standing Committee. He simply enlarged it and installed his own people.”

When Jiang stepped down as party general secretary in 2002, the Politburo Standing Committee was expanded from seven members to nine – more than half of them Jiang allies or proteges – it what was seen as an effort to undermine the power of new party boss Hu Jintao.

When Xi succeeded Hu at the party’s 18th national congress in 2012, the number of Politburo Standing Committee members was altered again, being trimmed back to seven.

Both changes – the increase and the decrease in the size of the Politburo Standing Committee – took place during decennial changes at the very top of the party hierarchy, marked by the succession of a new general secretary. Its size has tended to be stable at other times.

But while next year’s 19th national congress will not see a change at the very top, the fact that up to five of the Politburo Standing Committee members could be forced into retirement by informal age limits – plus Xi’s increasing dominance – has some people speculating that the number of seats could be reduced.

The conventions governing the composition of the Politburo Standing Committee could be easily bent, as there had never been clear, formal rules, said Kerry Brown, director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College in London.

“For all these rules, about retirement ages and sizes of committees, nothing is written down,” Brown said. ”It will be a simple calculation under the Xi leadership, which has shown itself to be highly tactical and political, of what sort of arrangements will help this leadership achieve its main goals.

“The priority now is to deliver, and rules that help in this will be observed, while those that don’t won’t be.”

Bo Zhiyue, director of the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington, said cutting the number of Politburo Standing Committee members to five would work in Xi’s favour because it would concentrate his power.

“The future composition of the Politburo Standing Committee might work against Xi,” Bo said. “The next echelon of cadres waiting to enter was arranged by others. They do not have backgrounds close to Xi.”

Xi’s proteges were relatively junior at the moment, Bo said, making it difficult for Xi to promote them to the Politburo Standing Committee directly, but elevating them to the wider Politburo was possible.

“There is a theory of queuing in the party: if I’m ahead in the line, there has to an explanation if I’m not promoted first,” he said.

The queueing convention originated in the Deng era and was a reaction to the meteoric promotion of left-wing fanatics in the last days of Mao’s reign. Deng said “good seeds shall be promoted stair by stair”.

Being able to muster a majority in the Politburo Standing Committee is important as the secretive body is supposed operate as a consensus-driven collective leadership, with the party general secretary only “first among equals”.

Jiang was quoted as saying on more than one occasion that “we are a team and as the team leader I only have one vote too,” according to his officially endorsed biography, The Man Who Changed China.

Reducing the size of the Politburo Standing Committee would make it easier for Xi to win majority support, said Professor Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at SOAS University of London.

“Reducing it to five will mean that he is likely to have a clear majority of supporters – he would only need two allies to have a majority,” Tsang said. “But getting there is the tricky bit. The establishment as a whole will fight tooth and nail to resist this, if this were Xi’s plan.”

But Tsang said such discussion was largely speculative at the moment.

“As politicians say, a week is a long time in politics,” he said. “A year in advance is eternity. Who knows what will happen a year from now.”