Top Chinese researcher’s move to US sparks soul-searching in China

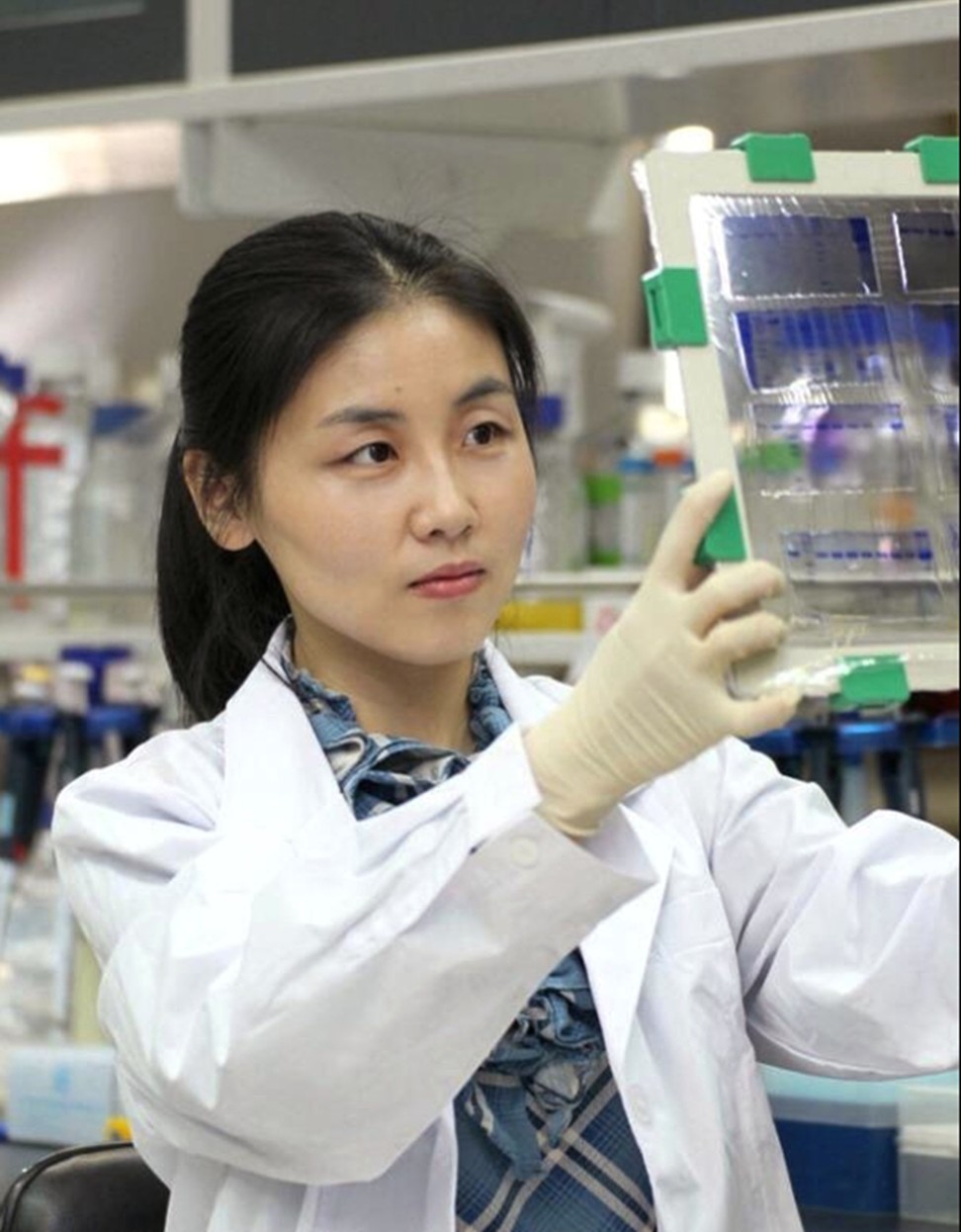

‘Goddess scientist’ Nieng Yan, once touted as a key example of Beijing’s success in luring back talent, is returning to Princeton University

The departure of a top Chinese researcher for an Ivy League university in the US has sparked soul-searching in China about whether the country’s unwelcoming research environment is sabotaging its efforts to retain its best talents.

American-trained life scientist Nieng Yan is leaving Tsinghua University to rejoin Princeton University this autumn after a decade of working in China.

Yan would take on a full-time professor role at Princeton’s department of molecular biology, state news agency Xinhua confirmed on Monday. Talk of Yan’s move had been making its rounds in the research community for months.

Yan, 40, had been one of China’s most prominent examples of top research talents the country had managed to lure back from overseas in recent years amid a transition to an innovation-driven economy.

She had been dubbed China’s “Goddess scientist” by mainland social media for her stylish looks, outstanding research work and willingness to openly criticise the country’s research environment.

For years, China has used financial incentives and patriotic appeal to bring back talented Chinese researchers who had studied and worked overseas. The Ministry of Education records more than 2.6 million “haigui”, or returnees from overseas, since 1949.

But a reverse trend of “guihai”, or people returning overseas, has emerged in recent years, and Yan will soon join their ranks.

The top researcher returned to China in 2007 after completing her post-doctoral research in Princeton. Aged 30, she became one of Tsinghua’s youngest professor.

During her time in Tsinghua, Yan’s research team made important breakthroughs. In 2014, her team became the world’s first to discover the physical structure of a protein related to a wide range of diseases including cancer and diabetes.

But that same year, she posted on her personal blog a detailed account of how the government-run National Natural Science Foundation had rejected her team’s grant application, criticising fund management officials for their reluctant to support high-risk research.

“Aren’t key research funds supposed to support risky but important research? Or are they only to support projects with predictable results and guaranteed success? Is that the way for innovation?” Yan wrote then.

She updated her blog post a year later to say that her project had again failed to secure an interview with the funding agency.

In an interview with Guangming Daily published on Monday, Yan said she received Princeton’s job offer back in 2015.

On her decision to relocate, she said: “I was afraid being in an environment for too long would make me ignorant without me even knowing it. “Changing my environment will … hopefully help achieve new breakthroughs in science.”

She added that she would do her best from Princeton to help Tsinghua on international collaboration. The South China Morning Post could not reach Yan for comment.

A Tsinghua University spokesperson, who was not named, told Guangming Daily that Yan and other top researchers’ departure showed that Chinese professors were qualified to teach in the world’s best universities and that this shed new light on China’s growing research strength.

“We believe this will help bring China’s academic thinking, educational belief and the research style of Tsinghua to the international stage to make a bigger impact,” the spokesperson said.

Chai Jijie, another life scientist formerly working in Tsinghua, started as a Humbholdt Professor at the University of Cologne in Germany last month.

On Sciencenet.cn, the largest online community of Chinese researchers, people blamed Yan’s departure on the government’s failure to properly manage its science talents and their research environment.

More research talents would soon pack up and leave as Yan was not the only one facing such bureaucracy, the critics warned.

“This is an alarm,” said a Shanghai-based life scientist who declined to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue. “The authorities must realise scientists care about a lot of things, and it is difficult to make them stay just for money or patriotism.”

A 2015 survey by Beijing-based think tank, the Centre for China and Globalisation, found that nearly 70 per cent of returnees from abroad wanted to return to work overseas.

Their reasons included hope for higher salary, a lack of job satisfaction, and concerns over food safety scandals, their children’s education, high housing prices, complex interpersonal relations and cultural conflicts.

Their biggest motivation to move, however – as cited in nearly 40 per cent of interviews with the respondents – was to escape China’s serious pollution.

Even so, Beijing continues to draw considerable numbers of overseas Chinese talents as it grows its research budget.

In more sensitive areas, such as dual military-civilian technologies, Chinese researchers may find more and greater opportunities returning home than staying abroad.

Duan Yibing, a science policy researcher with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institutes of Science and Development, said Yan’s departure for Princeton did not mean China was losing to American in its battle for talent.

“Princeton is more of an international research institute than it is American,” Duan said.

“Good scientists like Yan are international citizens. They should have the freedom to choose to work and live wherever is best for their research. This free flow of talent around the globe will eventually benefit the entire human race.”