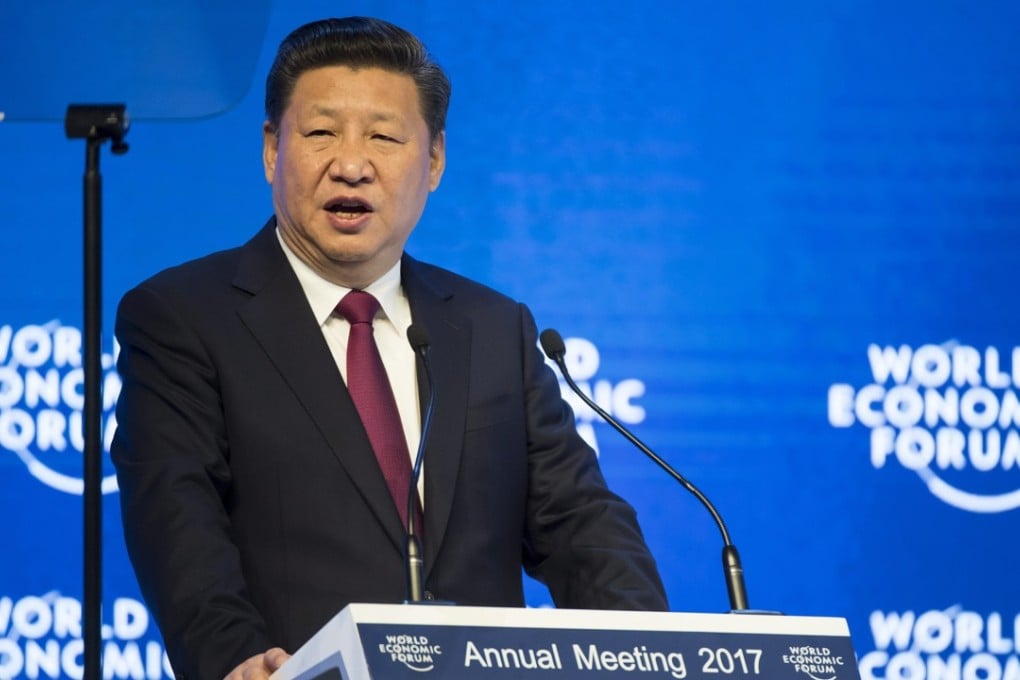

Being Xi Jinping: the difficult art of juggling growth and control after China’s Communist Party congress

Party chief on track to achieve first ‘centennial goal’ in his second five-year term

Chinese leader Xi Jinping inherited two lofty economic targets and a difficult juggling act when he became Communist Party general secretary five years ago.

He is on track to achieve the first of the party’s “two centennial goals” in his second term, beginning this month, but has a mixed record on promised economic reforms.

Faced with social and economic challenges that have generated calls for fundamental reforms in areas such as the state’s role in the economy, financial system risks and environmental protection, Xi has opted for a stability-first approach that emphasises party and state control.

There was tension between Xi’s economic and political objectives, said economist Louis Kuijs, from Oxford Economics, but “Xi feels the political dimension is very important. He has to preserve the existing system; accept that it may mean slightly less efficiency.”

The performance and stability of China’s economy are taken very seriously by the party, which prides itself on having lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty, because they underpin the legitimacy of its rule.

The “two centennial goals” were introduced two decades ago by then party chief Jiang Zemin. The first is to build a “moderately prosperous society” by 2021, the centenary of the founding of the party. The second is to become a “fully developed nation” by 2049, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic.