Why a Xi Jinping protégé came under fire in Beijing over mass eviction of migrant workers

The capital’s party secretary, Cai Qi, initially called for ‘tough’ response in wake of deadly blaze last month

Around a dozen uniformed police stood impassively, shoulder to shoulder, at dusk in Beijing, their faces half covered by masks in the wintry November mist.

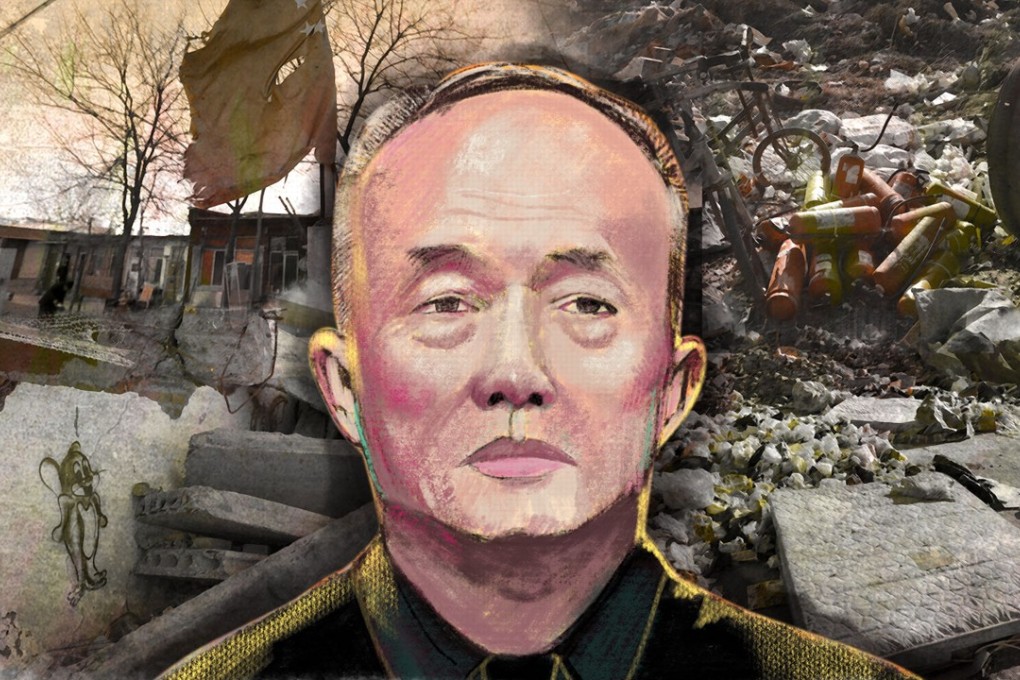

It was an image that went viral in China because they were guarding piles of wreckage, all that was left of buildings that were once home to thousands of rural migrants in the Chinese capital.

The devastation was not caused by an earthquake or explosion but was the result of a hasty demolition operation that resulted in the forced eviction of many members of Beijing’s migrant worker population.

Along with the buildings, the demolition campaign also shook the foundations of the ruling Communist Party’s legitimacy and dealt a blow to the image of Beijing party secretary Cai Qi, a protégé of President Xi Jinping with a reputation as a smooth social media operator, just six months into the job.

Videos of police kicking open the doors of flats and photographs of migrant workers sleeping on the streets after their flats were torn down also went viral, and overseas scholars accused the party, which prides itself as the protector of the proletariat, of practising social Darwinism.