Will China’s next vice-president have more power?

Appointment of former anti-graft tsar Wang Qishan likely to see office emerge from ceremonial shadows

After the assassination attempt on US president Ronald Reagan in March 1981, vice-president George H.W. Bush stepped into the breach, famously telling a military aide as he sped towards Washington that “only the president lands on the south lawn”.

But the concept of a vice-president would probably have confused many Chinese because the country did not even have a president at the time.

The 1975 constitution that was in force, dubbed the Cultural Revolution constitution, deliberately omitted the posts of state chairman and state vice-chairman – the previous equivalents of president and vice-president – because supreme leader Mao Zedong was worried a president would be regarded as his heir apparent.

Mao died in 1976, but it was not until 1983 that constitutional revisions revived the posts of state chairman and his deputy.

The titles later morphed into president and vice-president but they carried nowhere near the significance of their American equivalents, with that of the vice-president, in particular, waxing and waning with the political tide.

With the office of vice-president being relatively powerless in China, Deng Yuwen, a former deputy editor of Study Times , a newspaper affiliated with the Central Party School, said its actual power largely depended on party politics.

“The law gives the vice-president little beyond nominal status,” he said. “The president is a nominal title, and the vice-president is even more so.

“A vice-president’s power is largely dependent on the holder’s status in the party, and whether he holds other titles in the party, such as the top policymaker on Hong Kong and Macau affairs, or the party’s ideology chief.”

During Bush’s two terms as vice-president – from 1981 to 1989 – China saw its first two vice-presidents since the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution. Both were veterans of the earlier revolution that brought the Communist Party to power.

According to China’s constitution, the country’s vice-presidents look a lot like their American counterparts. When authorised by the president, the vice-president could perform some presidential duties, it says, such as confirming the appointment of a premier, signing laws or declaring war following legislative approval. It also says the vice-president would be acting president in the president’s absence.

However, Chinese vice-presidents have never done any of those things.

China’s constitution, unlike the US version, does not say what should happen if a president is unable to discharge their powers and duties. The United States has seen a vice-president step in as acting president three times – each for a matter of hours – but that has never happened in China.

Ulanhu, an ethnic Mongolian and a veteran communist revolutionary, became China’s vice-president in 1983, when the president was Li Xiannian. Five years later, when Yang Shangkun became president, Ulanhu was succeeded as vice-president by party elder Wang Zhen, known for his ironhanded rule of restive Xinjiang.

Ulanhu was 77 when he assumed office and Wang Zhen 80. After decades of service in the military and the state administration, their vice-presidencies involved little work beyond receiving foreign guests at welcoming ceremonies, and neither led a delegation to a foreign country as vice-president. More important diplomatic events were left to paramount leader Deng Xiaoping or younger cadres.

Wang Zhen’s voice did matter in China’s elite politics, but only because he was one of the party’s “Eight Immortals”, elders who in the 1980s met as the Central Advisory Commission and pulled all the strings behind the scenes.

Wang Zhen visited the US in 1985, three years before he became vice-president, and met then US vice-president Bush, but his formal title at the time was president of the Central Party School.

After the West turned its back on China following the military crackdown on pro-democracy protests in 1989, China picked Rong Yiren, a prominent businessman dubbed the “Red Capitalist”, as its vice-president in 1993. Rong was only revealed to have been a party member after his death in 2005.

When Dick Cheney, sworn in as US vice-president in 2001, rose to become the most powerful holder of that office, he was able to meet two Chinese counterparts representing two other types of Chinese vice-president.

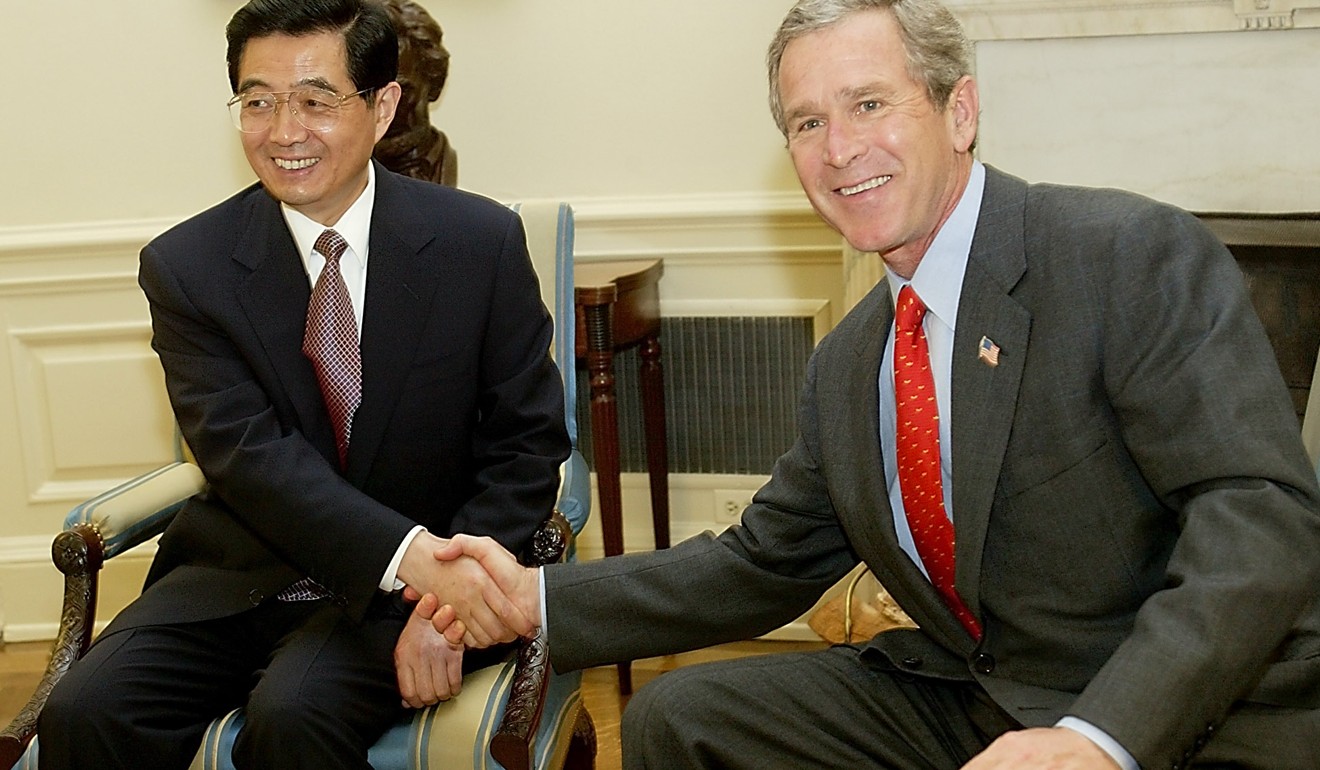

Cheney met then vice-president Hu Jintao in Washington in 2002, when Hu had already been designated China’s next top leader by Deng. Hu’s five-year vice-presidency was intended to prepare him to succeed president Jiang Zemin and increase his exposure to foreign leaders.

After Hu became president in 2003, vice-president Zeng Qinghong became Cheney’s Chinese counterpart. Zeng’s background as the son of a renowned revolutionary and his close ties with Jiang diluted Hu’s power, even though Zeng was too old to challenge for the top position himself.

When Zeng proposed retiring as the party’s ideology chief and state vice-president in 2007, he was powerful enough to broker a deal that traded his retirement for a Politburo Standing Committee seat for Xi, giving the younger man the platform from which to aim higher.

Xi’s vice-presidency followed a similar path to Hu’s. During a visit to the US in February 2012, nine months before he became party leader, Xi was accompanied by US vice-president Joe Biden throughout the trip and also met celebrities such as basketball player Earvin “Magic” Johnson and soccer player David Beckham.

Though Xi was a powerful figure in the party, he never sought to challenge Hu’s polices or stand out from his Politburo Standing Committee colleagues during his five-year vice-presidency, which ended when he succeed Hu as president in 2013.

China’s vice-presidency was then reduced to a ceremonial role once again, with Li Yuanchao, a Hu ally, filling in the post. Li Yuanchao became the first vice-president in 15 years not to be a member of the party’s innermost Politburo Standing Committee, which kept him out of the loop on top-level decisions.

Li, who turned 67 in November, stepped down from the 25-member Politburo after the party’s national congress in October even though he had not yet reached the party’s unofficial retirement age.

If as expected, Wang Qishan succeeds Li Yuanchao as vice-president next month, it will be a break with a pattern dating back two decades. Hu, a presidential heir apparent, was succeeded by Zeng, a close ally of the previous president. Heir apparent Xi and Li Yuanchao, a weaker Hu ally, repeated that pattern, but Wang Qishan’s appointment would appear to have more in common with the earlier preference for vice-presidents who were trusted party elders. It would also mean there would be no heir apparent identified for Xi as he begins his second five-year term as president.