Why protests by China’s truck drivers could put the brakes on the economy

Truckers keep the vital e-commerce industry moving but they’re in an uphill battle against rising costs and a lack of labour protections

Truck owner Du Yun and his co-driver have just a completed a 1,600km (1,000 mile) trip to a freight hub in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou but they are anxious to get back on the road.

The clock is ticking and they waste no time loading the cargo of face masks and shampoo onto Du’s new 49-tonne vehicle for the return leg to Chengdu in Sichuan province.

The non-stop trip will take a little over a day but they need to get moving to outrace the pack of expenses threatening their basic financial survival.

Du’s monthly repayments on his truck – which he bought two months ago to meet new vehicle emissions standards and aims to pay off in two or three years – come to 20,000 yuan (US$3,100) alone and he struggles to cover in an increasingly cutthroat transport sector.

“We generally made about six trips per month last year. But business has been bad this year. We are already halfway through June and we have only made two trips so far,” he said.

The long trips, the stress and the uncertainty are taking their toll not only on Du but on the roughly 30 million truck drivers around the country, who are the lifeblood of a delivery system that keeps China’s 24 trillion yuan e-commerce industry moving.

E-commerce is central to the Chinese government’s efforts to shift the economy away from export-led growth towards consumer spending, and on any given day more than 84 million tonnes of freight are transported across the nation’s massive highway network, roughly 80 per cent of the national total, according to a widely cited 2017 study by Chinese logistics technology company G7.

But the truck drivers who move those goods are running into a brick wall of skyrocketing fuel costs, tolls, truck loans, falling rates, arbitrary fines and declining orders, posing a new labour challenge for the authorities.

STRIKING BACK

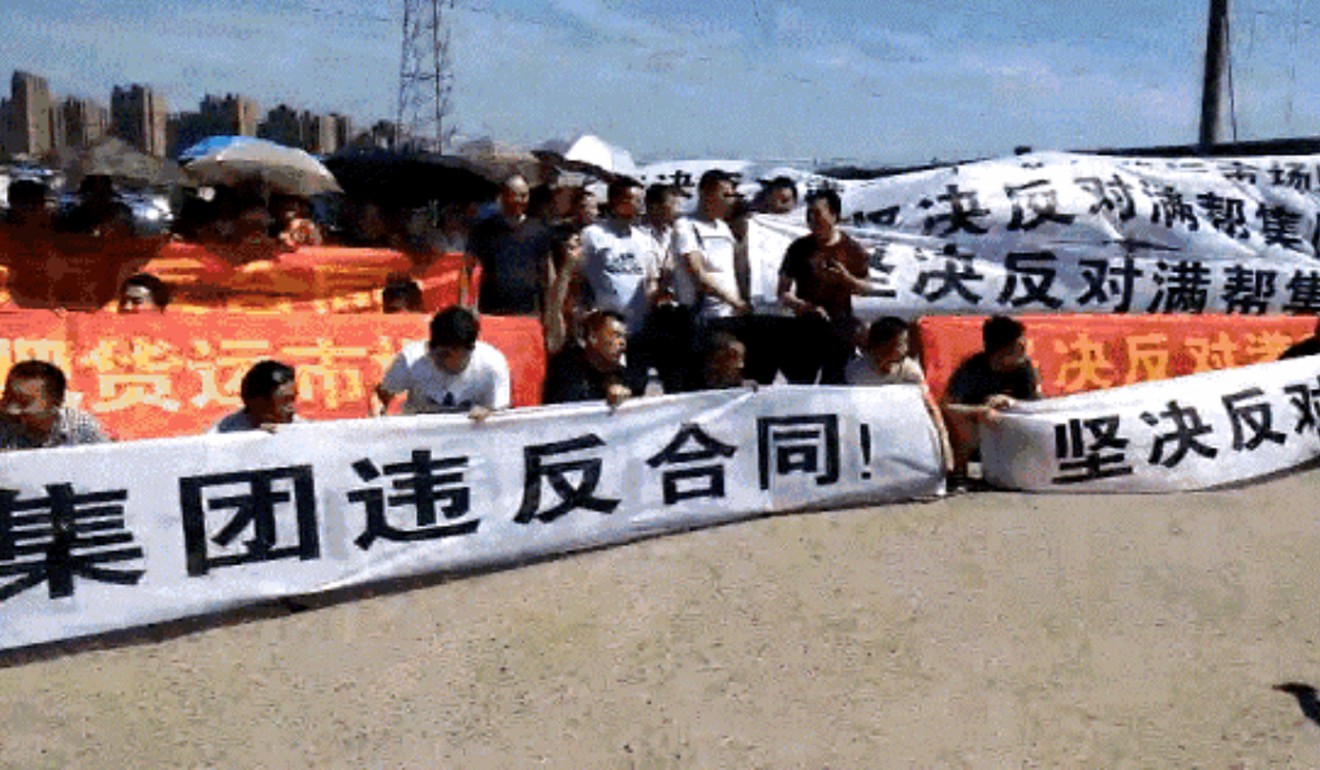

Those frustrations spilled over into protests earlier this month when drivers mounted strikes in at least a dozen places across the nation, including the megacities of Shanghai and Chongqing as well as Anhui, Hunan, Henan, Shandong and Shaanxi provinces.

Hong Kong workers’ rights group China Labour Bulletin said thousands of drivers took part in the protests but news of their actions was censored in China.

According to photos and videos of the protests on social media, the truckers drove slowly on motorways, honking horns, chanting slogans and holding up banners saying how hard it was for them to make a living.

“We must survive, we must feed our families,” the drivers chanted in one of the videos.

Observers said that if the truckers’ grievances were not addressed, the action could spread and paralyse the logistics and e-commerce industries in the next two to three years.

“The drivers have successfully launched a nationwide strike erupting in multiple regions without external intervention, this is a breakthrough,” Chris Chan King-chi, a labour expert from City University of Hong Kong, said. “I think the government is required and will respond to their appeals soon.”

In the meantime, the authorities have resorted to traditional methods to manage the dispute.

Du, who trucked vegetables from Chengdu instead of joining the strike, said many of those who did demonstrate were taken away by police.

And one unidentified driver from Yantai, Shandong province, was summoned overnight and interrogated by the city’s public security department after speaking to the South China Morning Post.

THE LONG ROAD

Even when the orders come in, the conditions are gruelling. According to a Social Sciences Academic Press study released in April, most Chinese truck drivers work up to 12 hours a day and more than 70 per cent who own their own trucks cannot afford to employ a relief driver.

Wang Xianping, a 45-year-old driver from Hubei, said a driver could earn about 17,000 yuan for a 2,500km round trip between Wuhan in central China and Shenzhen. That left about 5,000 yuan per trip after fuel and tolls, but most of that would go to paying off truck loans.

“After the truck payment, it’s really not enough to support my family,” he said.

On top of that, Wang said he lived away from his family and would get just four hours of sleep on a 24-hour trip.

“Throughout the year, I live in a small flat with several other truckers away from my wife. But what I earn is still not enough to pay loans and living costs. That’s what drove the drivers to take to the street,” said Wang, who did not take part in the protests.

The strikes were scattered but they were organised and different from the industrial action workers have staged over the last few decades. China’s truck drivers are a sizeable network of highly mobile people connected via supportive, tight-knit internet communities. They move and communicate on the road across the country, unlike like workers in traditional factories.

Professor Pun Ngai, a leading Chinese labour studies expert at the University of Hong Kong, said the drivers were better organised and had more bargaining power.

“Most are self-employed contractors so they … tend to fight harder for themselves compared to traditional workers,” Pun said. “The government needs to be worried but not for political threats but for the economic impact their industrial action can have on the entire supply chain.”

She said the strikes were harder to ignore because the impact was not confined to an individual plant or corporation.

LABOUR PAINS

The precarious situation of truck drivers – and their self-employed brethren in the delivery and courier business – is in part because they are not covered by the country’s labour law.

China introduced the Labour Contract Law in 2008, improving worker protections through compulsory formal employment contracts. But the percentage of workers covered by formal contracts has dropped from 42.8 per cent in 2009 to just 35.1 per cent in 2016 as the country’s economy has moved from away manufacturing to services.

“It took China’s manufacturing industry a long time to secure stable employment protection for workers but all that changed in just a few years with an influx of technology companies,” Chan said.

“Technology is not only replacing human labour but is changing the employment model to cut costs.”

Chan said China was a latecomer to capitalism and so had weak regulatory foundations. Its economy was also changing at head-spinning rate, adding up to the intense competition felt by the truck drivers.

And there is more change on the horizon. Last month, e-commerce giant JD.com unveiled its autonomous truck technology designed to replace manned-trucks one day.

“There isn’t much value if our technology can only cut three drivers down to two or even one. We hope the truck is unmanned,” Xiao Jun, president of JD’s X business division, said.

Pun said the labour contract law should be strictly implemented across all industries to protect workers, including the self-employed.

“Disputes are erupting non-stop. Without labour contracts, many self-employed people are working long hours, suffering from occupational hazards and accidents without any crash barrier,” she said.

Industry-based unions should also come up with more innovative ways to help workers.

“Strikes will always be on the rise in China as long as it continues to lack labour protections … Over years of field studies, I have seen that conflicts continue to accumulate,” Pun said.

For Du, the future is bleak in a high-risk occupation that requires him to put in long hours and sleep and eat on the road while juggling hefty truck loans, fines and surging fuel costs.

“I want to be a courier in Shenzhen or Beijing. Not many young people are entering this profession any more. It doesn’t have a future,” he said.