Still taboo in mainland China: the Cultural Revolution as seen through the lens of Li Zhensheng

- Award-winning photographer still hopes that his countrymen will one day be able to see the images taken at the height of the turmoil

- Pictures that had to be hidden away for decades are still deemed too sensitive to be shown to the Chinese people

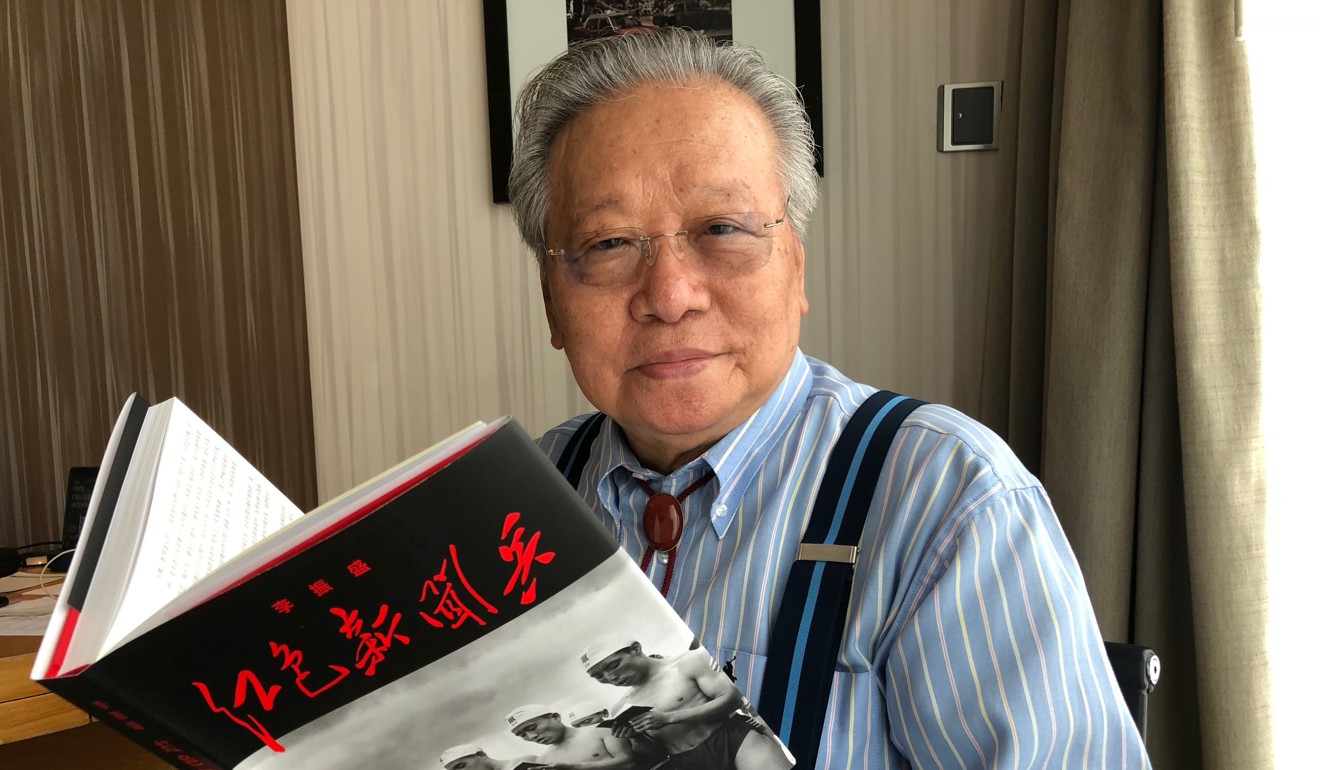

Photographs taken at the height of the Cultural Revolution and subsequently hidden away for decades brought Li Zhengsheng international acclaim when he was finally able to publish them.

But the award-winning photographer will almost certainly never see his album Red-Colour News Soldier: Li Zhensheng on sale in his homeland.

It was only in July this year that the first Chinese-language edition of the award-winning collection, which has already been printed in six languages was published in Hong Kong.

The 78-year-old still hopes his work will reach more Chinese people, but for now it has to be smuggled onto the mainland.

“It is impossible … Any book about the Cultural Revolution and important historical incidents has to be submitted [to the authorities] for approval. You can submit it, but they will not approve it,” he told the South China Morning Post during a recent visit to Hong Kong.

Li occasionally receives messages from readers who tried to take the Chinese edition they bought in Hong Kong through customs, but said: “I have personally received messages from two to three readers that the book had been confiscated during random searches at customs.”

Cultural Revolution through the lens of a Chinese photographer

But Li still hopes that one day most his readers will be Chinese.

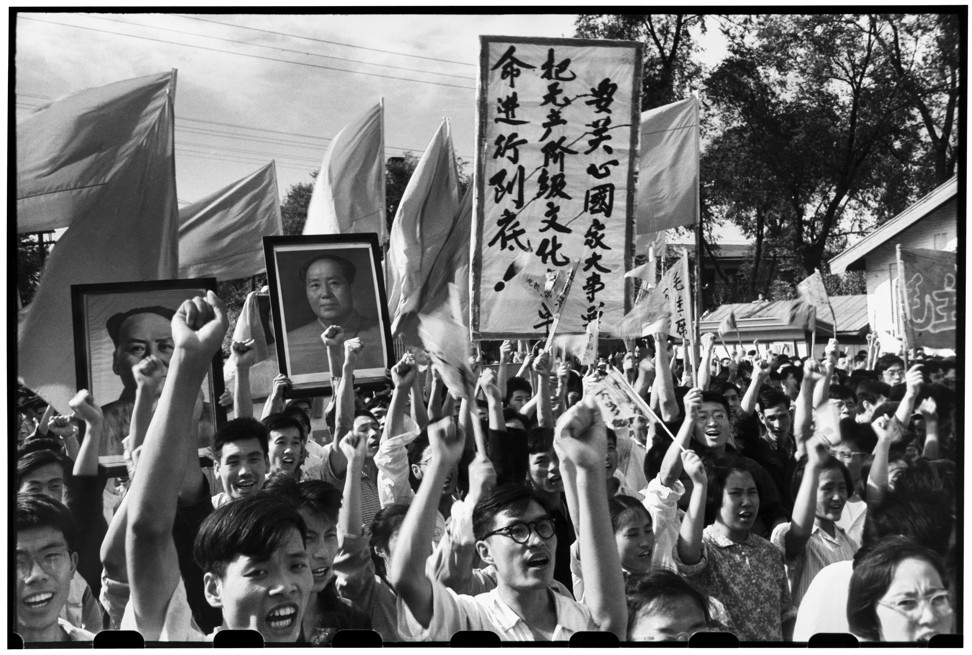

“The Cultural Revolution took place in China, but research into the Cultural Revolution flourishes in other countries and it has little impact on China. I really cannot accept this.

“My photos were taken in China and most of my readers should be in mainland China, whether or not they have experienced the Cultural Revolution.”

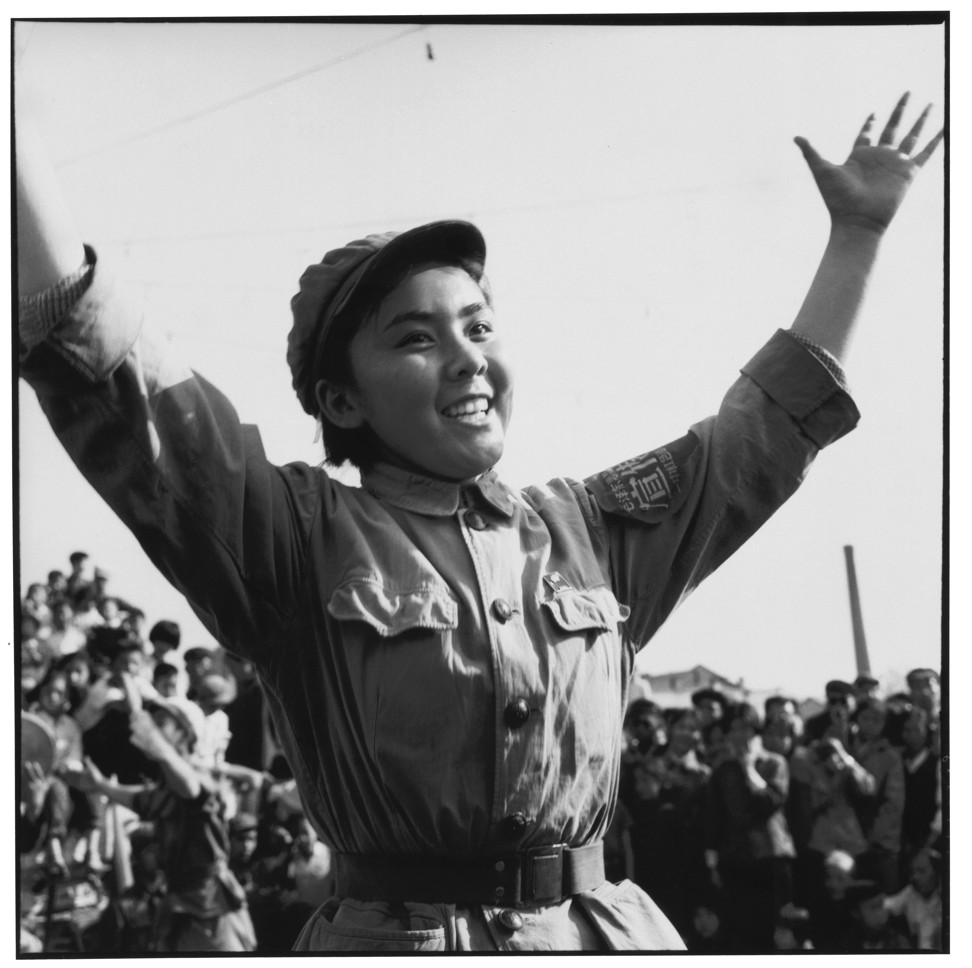

He said the pictures would resonate with those who experienced the Cultural Revolution first-hand, while the younger generations should know about the journey their grandparents or parents had taken.

“Many people who have seen the photos would say could this be possible? How could there be such photos?

“Only when people feel the resonance can there be contemplation, and only deep contemplation can lead to reflection. Only with that reflection can there be changes in people’s ethics.”

He warned that the “soil of the Cultural Revolution still exists” although it would take a different form if it manifested itself.

He highlighted the so-called red song campaign launched by the now disgraced Chongqing party boss Bo Xilai and the Maoist website Utopia, recently closed by the authorities, as examples.

Book review: The Killing Wind is not for the faint-hearted as it charts Cultural Revolution horror

Li said he found it strange that Chinese high schools only dedicated one lesson to the history of the Cultural Revolution, while some American universities such as Harvard offered specialised three-year courses on the subject.

“Now they [the Chinese authorities] have even changed the topic of the lesson from what is called ‘10 years of disasters’ to ‘a difficult exploration’,” he said.

“Ten years of disaster means it is a mistake. But difficult exploration means [the Cultural Revolution] was like touching the stones to cross the river. Who would use the livelihood of hundreds of millions people for this kind of exploration?”

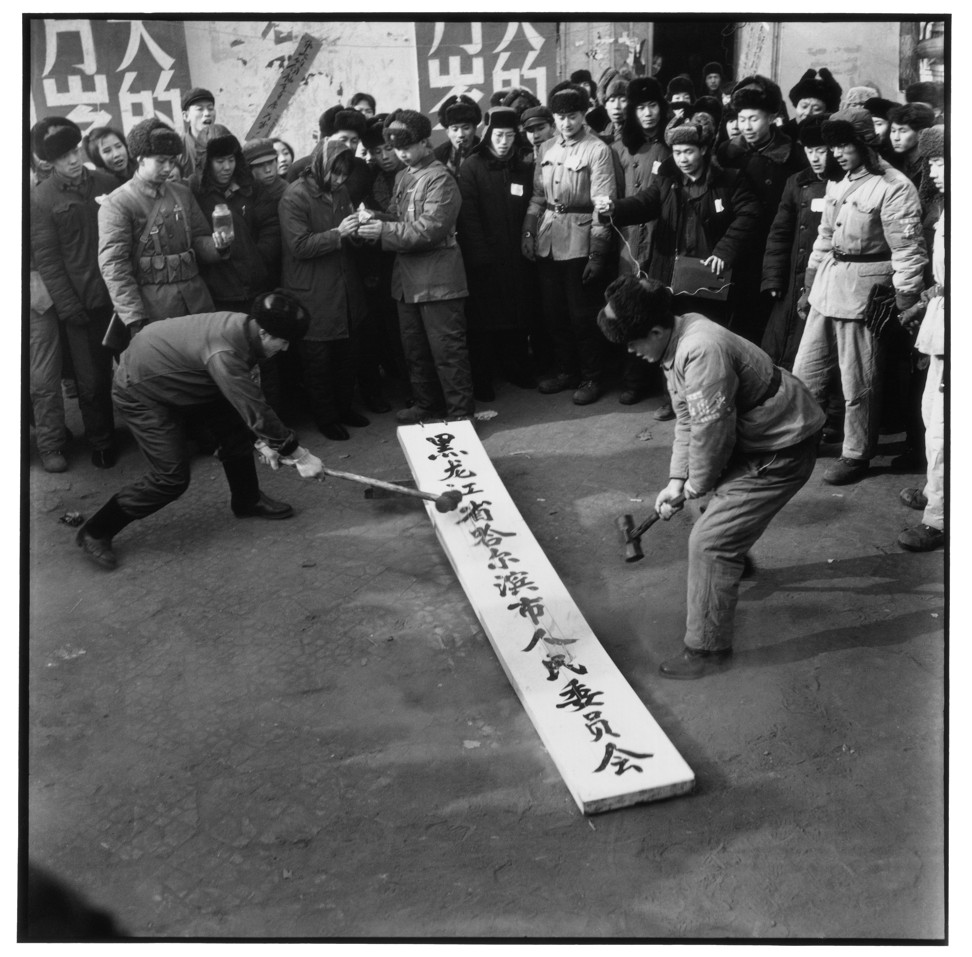

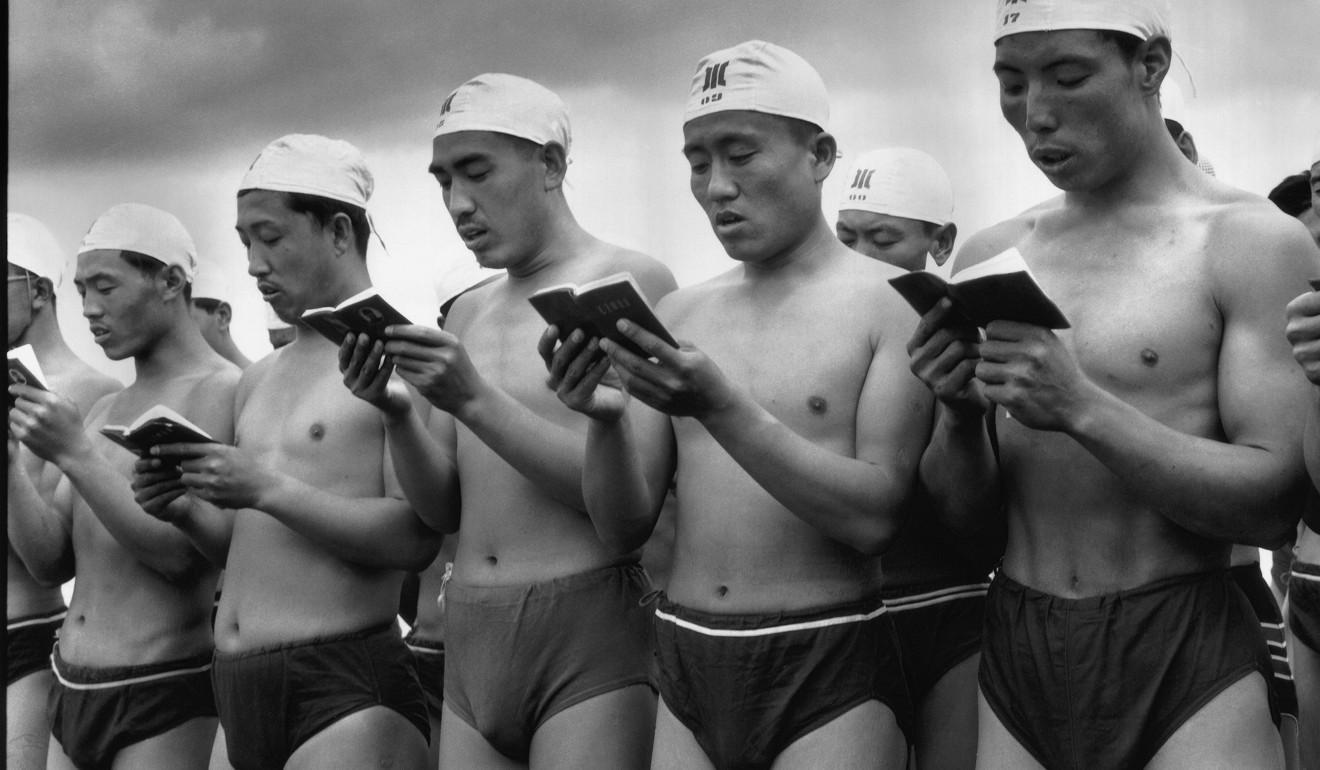

Li was working as a photojournalist for Heilongjiang Daily in the northeast of the country at the start of the Cultural Revolution and the title Red-Colour News Soldier refers to the writing on the armband he wore at the time.

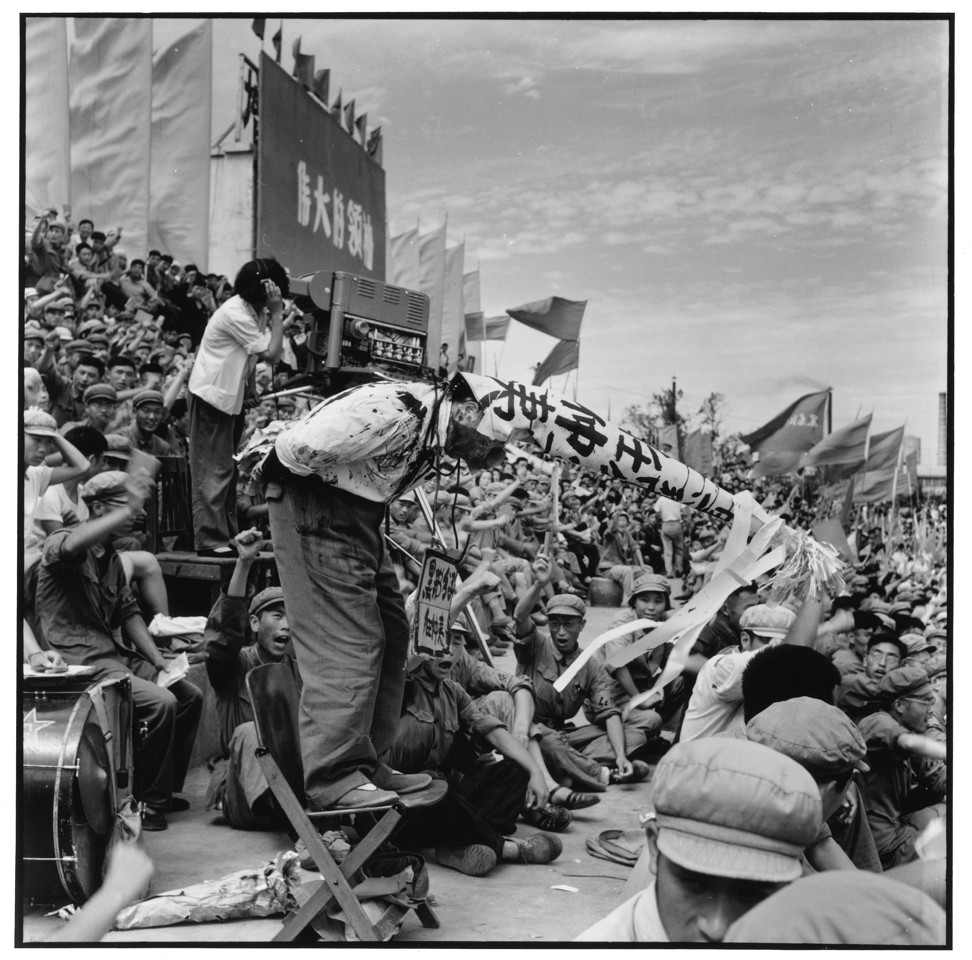

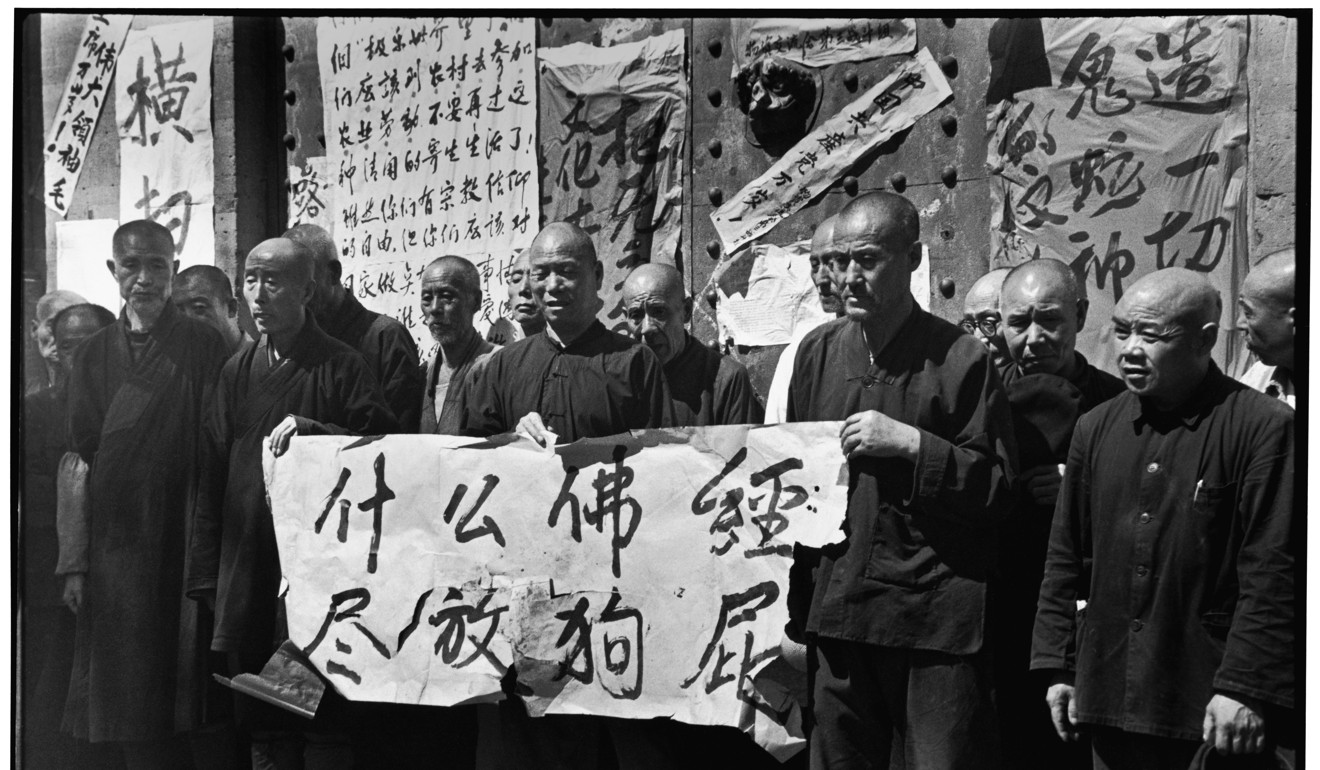

He secretly took tens of thousands of photographs presenting the dark side of the Cultural Revolution, developed them in the office at night, hid them in secret compartments in his desk, before moving them back home and storing them under the wooden floor of his home.

He ended up hiding 20,000 negatives taken between 1966 and 1968 when the public humiliations, attacks and denunciations were at their most ruthless.

At the time the propaganda machine would only allow “useful” photos that showed the happy lives of the proletariat and the greatness of Chairman Mao Zedong to be published.

Top Chinese cadre criticises Cultural Revolution for harm to tradition

The photos were first made known to the world in 1988 when Li entered 20 of them into a national photography exhibition and won the grand prize.

He said it was only possible to show them because of the “loose” political climate at the time, referring to the freest period in Chinese politics when reformist Premier Zhao Ziyang was in power.

Zhao was ousted the following year amid the Tiananmen Square protests.

The national award did little to help Li’s photos get published in mainland China.

It was only when Li was invited to Harvard University as a visiting scholar in 1996 that he was finally able to show them to the wider world.

From then on he brought the negatives, already hidden for over four decades, bit by bit to the United States during numerous trips before emigrating to America for good.

With the help of Robert Pledge, co-founder of Contact Press Images, about 300 photos from his collection were published in 2003. His photos have won him many international awards, including a Lucie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Documentary Photography in 2013.

The album contains both banned photos and those accepted by the authorities.

“Those photos showing struggle sessions when people were shaved, wearing tall hats [of humiliation], have their homes searched, and executed [as shown in the album] were banned by the authorities,” he said.

The only exception was the picture showing Ren Zhongyi, the former party chief in Harbin city, wearing a dunce’s hat and being publicly humiliated.

Ren, who later became a reformist party secretary in Guangdong, gave his permission for the image to be shown, even adding his signature to it.

Since Li’s rise to fame, there have been attempts to publish some of the photos in the mainland. However, the images were only allowed to be published in an autobiography, where the Cultural Revolution formed only one of the sections.

He has also been interviewed by the state broadcaster CCTV several times, but said, “only photos acceptable to the authorities are shown”.