Predicting Beijing’s thinking with the help of artificial intelligence and People’s Daily

- US economist’s program foretells China’s policy moves by analysing party mouthpiece’s front pages

- Algorithm shows ‘surprise’ when Beijing shifts strategic priorities

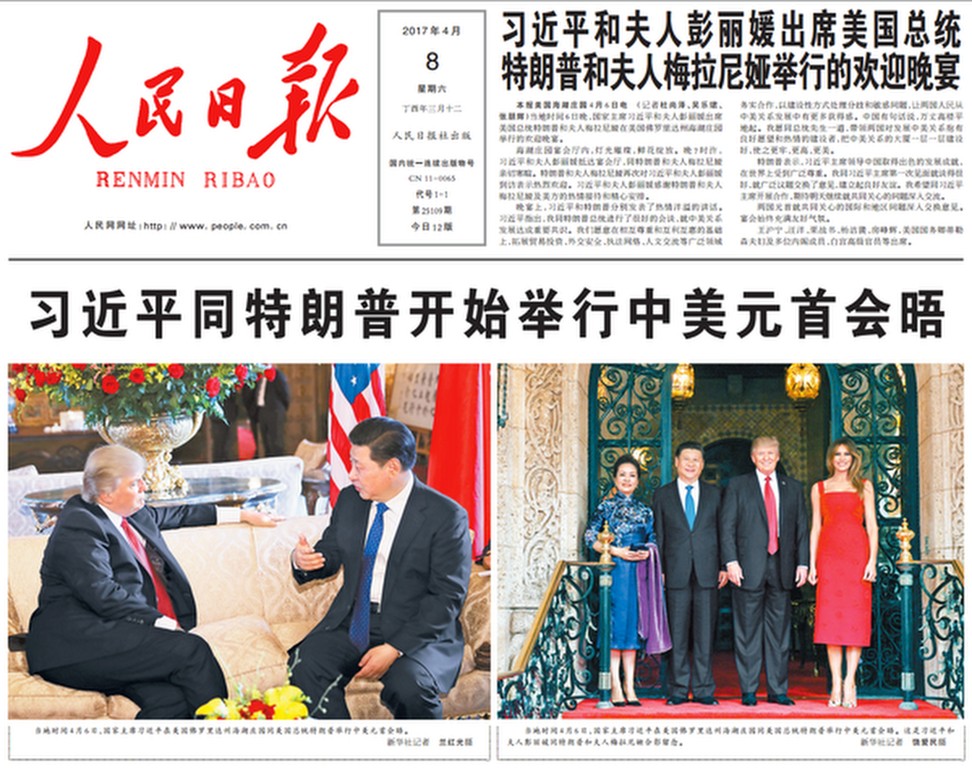

For decades, People’s Daily, an official newspaper of the Communist Party, has been a must-read for China watchers – a window on the policies, people and perspectives the party wants to be the focus of attention.

Now, an artificial intelligence program designed by an economist with an influential US think tank is analysing the party’s mouthpiece – and its propaganda – to provide those who report on the politics of China with a clearer idea of what Beijing is thinking and planning.

An AI programme developed in 2016 by Weifeng Zhong, a research fellow with the American Enterprise Institute, with Julian Tszkin Chan of the Washington-based Bates White Economic Consulting firm, assesses the policy priorities of the Chinese government by observing what policies appear on the newspaper’s front pages and how often.

An algorithm in the newly launched program has read and memorised all the articles in People’s Daily, which was established in 1948, and in a predecessor publication which existed for two years before the newspaper’s official founding.

If the algorithm is constantly “surprised” by the policies that appear on the journal’s front page over a certain period, the conclusion is that the government is changing a policy – or adjusting the priorities underlying one.

Zhong explained what the algorithm aimed to accomplish, in a paper that was recently published on the website of the American Enterprise Institute.

“Imagine an avid reader of People’s Daily, whose mind our algorithm will try to mimic,” he wrote. “If the reader had read, remembered and thought through all the articles published in recent times, it would have acquired a fairly good sense of what kind of articles ‘should’ or ‘should not’ appear on the front page.”

The program already has reached a preliminary conclusion about the new administration of President Xi Jinping.

Despite Xi's declaration that China has been in a “new era” since 2012, when Xi first took power, the programme has found “no change” in policy priorities compared with the previous administration.

“The status quo of policies in China had been the coexistence of maintaining the economic reform programme – though at a slower pace – and tackling social issues with populist policies,” Zhong argued in his paper.

The impetus for market reform began to ebb around 2004 during the administration of Hu Jintao under the slogan of Socialist Harmonious Society, coinciding with an increase in official wealth redistribution policies, Zhong wrote.

That said, the algorithm finds policy priorities under Xi the most difficult to comprehend, even more so than under the Chinese leaders of the 1980s, when intensive debates and factional struggles dragged on for almost an entire decade, Zhong said in an interview.

Zhong said the algorithm’s struggles “underlined the intense contradictions of Xi's policies. While he got tougher in reviving communist teachings and battling Western ideology, he also went further on market reform slogans”.

Xi's devotion to orthodox Marxism was most evident last year when he led the entire Politburo Standing Committee – the top echelon of the party – to Shanghai, where they paid homage to the party’s birthplace and founding fathers, and retook the party's admission oath.

The move was seen as a reinstatement of the commitment of the party to stick to the original values of the founding fathers – and no taking up of Western values.

Yet, rhetoric on market reform – long demanded by the West – remains high.

Beijing called for “letting the market play the decisive role in resource allocation” in a top-level policy blueprint in 2013, before enshrining the phrase in the constitution of the Communist Party in 2017.

The algorithm could be applied “to other communist regimes who used similar propaganda, including North Korea and Cuba”, the economist said.

Its Policy Change Index has picked up major shifts in policy during the beginning of the Great Leap Forward in 1958 – Mao Zedong’s attempt to modernise China’s economy.

The catastrophic policy resulted in the deaths of 20 million to 30 million people in what became known as the Great Famine.

The algorithm registered surprise at front page stories in People's Daily during the three years after Mao’s death in 1976. It grew “calm” again in 1978, as Beijing nailed down its “reform and opening up” policy.

The program is designed to benefit researchers by identifying the articles that have surprised it, and it

“predicted” significant policy change before progress on market reform accelerated in 1993 and before its slowing in 2004.

In both cases, the program detected a significant change in the discourse on the front pages of People's Daily.

The algorithm, however, failed to foretell the coming of the Cultural Revolution, a decade of social and political upheaval ordered by Mao in 1966, or the violent crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing in 1989.

In his paper, Zhong suggested the program failed to foresee the coming of the chaos because Mao hid his intentions.

The 1989 crackdown on the protests, Zhong argued, went unperceived because it was deliberately played down, being considered too sensitive by Beijing.