Exiled democracy activist Wei Jingsheng says China is going ‘further backwards’ 40 years after his landmark protest

- Harsh criticism for Beijing’s ‘one-party dictatorship’ undimmed after four decades

- Deng Xiaoping gets ‘too much credit’ for reform and opening up, he says

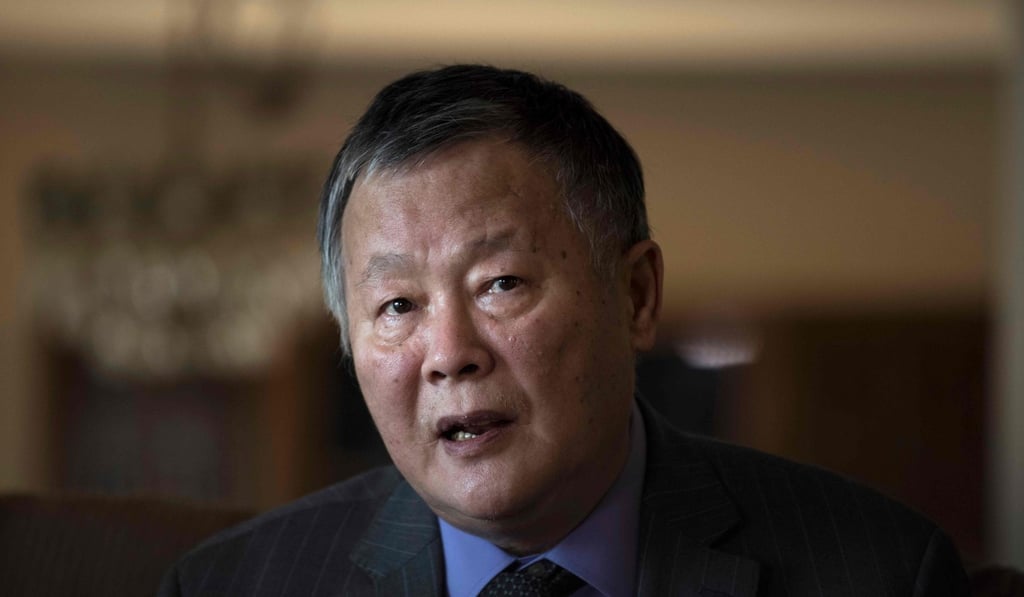

Exiled Chinese dissident Wei Jingsheng has rubbed shoulders with past presidents, including the late George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, during his two decades in the US, but these days prefers not to venture into the capital.

Wei, who is often called the father of China’s modern democracy movement, sat down for a lengthy interview at his home in a Maryland suburb south of Washington, on the eve of a landmark anniversary.

On December 5, 1978 he posted The Fifth Modernisation on a wall in Beijing, an essay in which he said Deng Xiaoping’s reforms did not go far enough, and called for democracy to be a goal for China.

Wei still welcomes visitors the Chinese way – by offering them a cigarette, then lights one for himself before unleashing harsh criticism of the “one-party dictatorship” in power in Beijing.

It’s a familiar battle cry: for four decades, Wei has railed against state oppression of the Chinese people’s democratic aspirations.