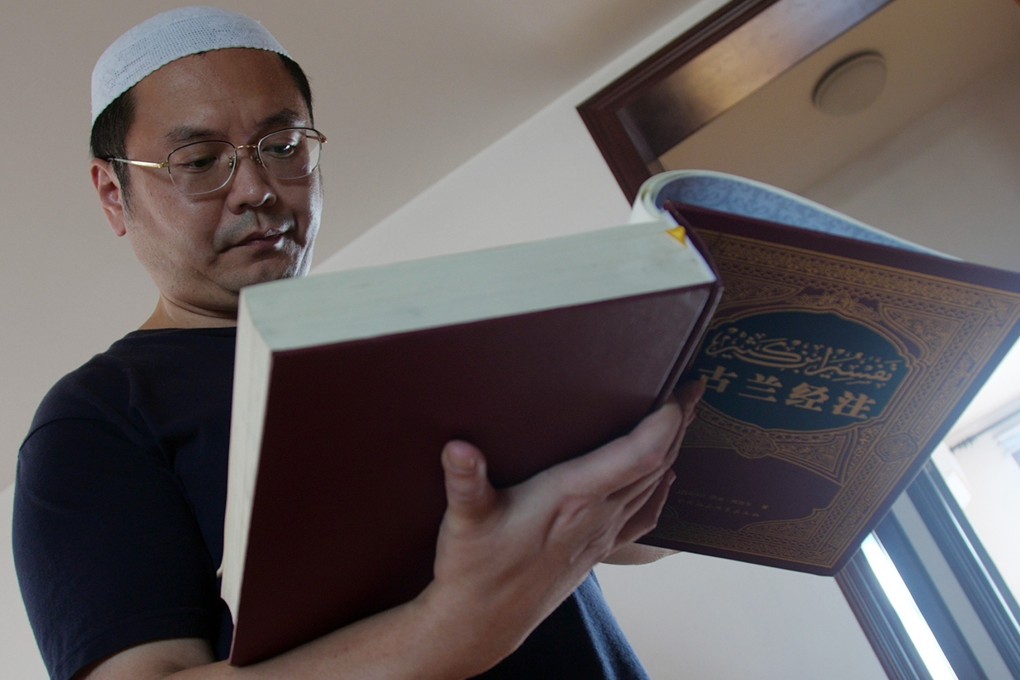

Chinese Muslim poet Cui Haoxin fears his people will suffer as history repeats itself in wave of religious repression

- Hui Cui Haoxin fears there will be violence if Beijing’s clampdown on Islam goes on

- Efforts to ‘Sinicise’ religion have led to arrests and closures at places of worship

Poet and religious rights campaigner Cui Haoxin is too young to remember the days of his people’s oppression under Mao Zedong.

The 39-year-old was born after the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, when the Hui – China’s second-largest Muslim ethnic group – were tormented by the Red Guard.

Since then, the Hui generally have been supportive of the government and mostly spared the kind of persecution endured by China’s largest Muslim group, the Uygurs.

But there are signs that that is changing, and Cui fears both that history may be repeating itself and for his own safety as he tries to hold the Communist Party accountable.

In August, town officials in the Hui region of Ningxia issued a demolition order for the newly built Grand Mosque in Weizhou, although they backed off in the face of protests.

More recently, authorities in nearby Gansu province ordered the closure of a school that taught Arabic, the language of the Koran and other Islamic texts.

The school had employed and served mainly Hui since 1984. A Communist Party official from Ningxia visited Xinjiang, the centre of Uygur oppression, to “study and investigate how Xinjiang fights terrorism and legally manages religious affairs”.