The complex reality of China’s social credit system: hi-tech dystopian plot or low-key incentive scheme?

- A dozen or so cities throughout the country are test beds for carrot-and-stick programmes to encourage businesses and individuals to comply with existing rules

- The efforts have been roundly condemned overseas as Orwellian but for members of the public, the impact of the systems can vary

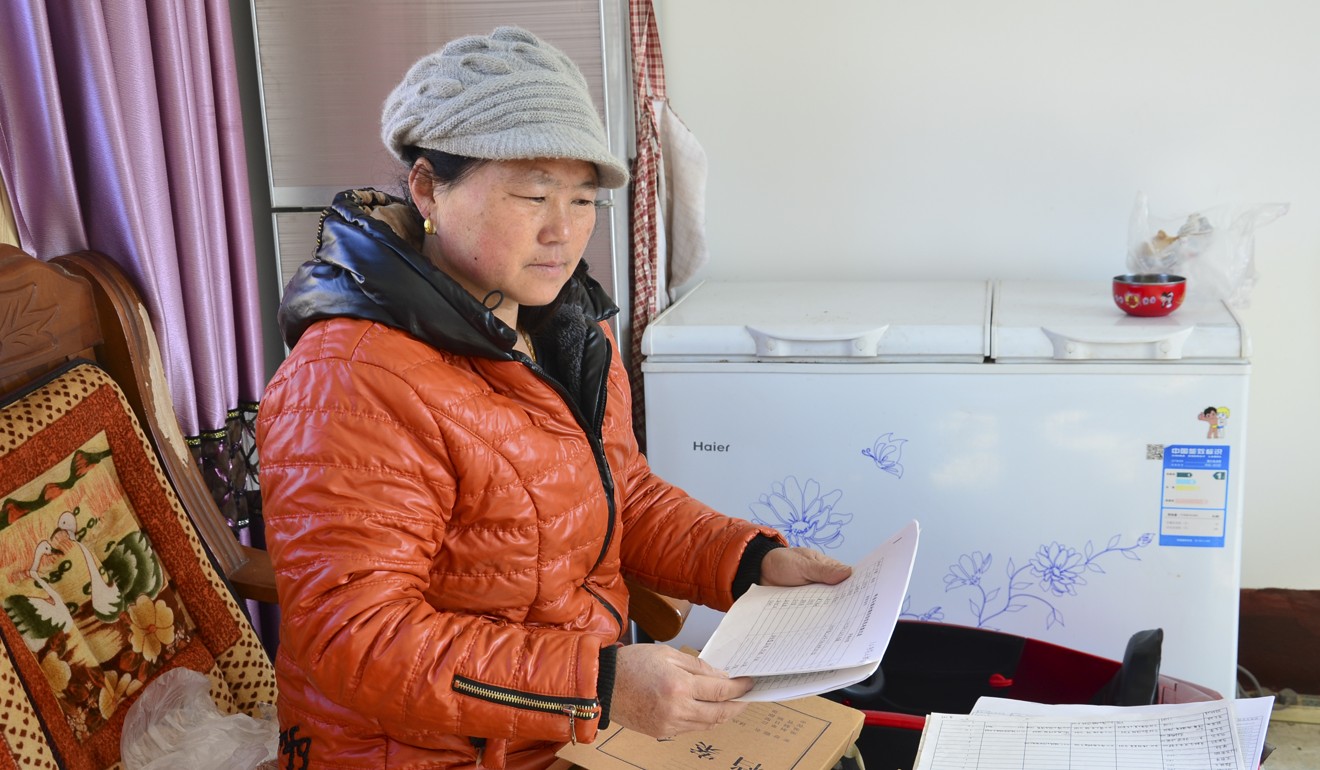

Yang Qiuyun’s home in eastern China heaves under a mountain of paper files. They are scattered on top of cabinets, piled on the water dispenser and stacked up on her bed.

The files are filled with forms completed in her neat handwriting, records of the laborious work she carries out as one of 10 “information gatherers” in a village at the forefront of an experiment in social management: China’s social credit system.

Every day, Yang, 52, roams Jiakuang Majia village with a pen and paper in hand, writing down every instance of free labour or other donations her fellow villagers make to the community – two points for Ma Shaojun for taking eight hours to install a new basketball hoop in the village playground; 30 points for Ma Hongyun for donating a 3,000-yuan (US$445) TV screen for the village meeting room; and 10 points each for Ma Shuting and Ma Qiuling who have a son serving in the army in Tibet.

The points are added to the villagers’ personal “credit scores”, which are tied to community welfare programmes. High scorers get more rice, cooking oil and cash rewards from the village committee and are lauded on village bulletin boards as role models.

At the same time, points are deducted for bad behaviour such as littering or neglecting care of elderly parents.

This is what China’s much talked about social credit system looks like on the ground in the countryside of Rongcheng, a sleepy city on the eastern tip of the Shandong peninsula and one of a dozen “model” centres lauded for their success in piloting the programme.

The system relies on a series of rewards and punishments meant to encourage people and businesses to abide by rules and to promote integrity and trustworthiness in society at large.

According to the official blueprint released in 2014, a national system will be rolling out by 2020 to “allow the trustworthy to benefit wherever they go while making it difficult for the discredited to take a single step”.

But as the Chinese authorities embrace new information technology to monitor, manage and control the public like never before, the prospect of a sweeping social credit system has raised alarm around the world, especially with the ever-tightening grip on civil society, rights activism and religion.

George Soros calls Xi ‘the most dangerous opponent of free societies’ due to social credit plan

The system made headlines just last month when billionaire investor and philanthropist George Soros told an audience at the World Economic Forum in Davos that the social credit scheme was “frightening and abhorrent”, and “would subordinate the fate of the individual to the interests of the one-party state in ways unprecedented in history”.

Soros also called Chinese President Xi Jinping “the most dangerous opponent of open societies”.

A few months earlier, US Vice-President Mike Pence described it as “an Orwellian system premised on controlling virtually every facet of human life”.

Some reports have framed the system as a hi-tech dystopia, where an algorithm dictates the lives of 1.4 billion people through a three-digit score, with points added or deducted in real time under the watchful eyes of AI-powered surveillance devices.

But in reality, only some pilot cities have scores and each does it in their own way. There is also no standardised national social credit score for everyone – instead there is a complex web of systems run by different ministries, levels of governments and regions interconnected by data sharing.

On the ground

Even when there is a scoring system in one area, its effects are felt very differently throughout the community.

It is just part of the government’s usual propaganda. It has nothing to do with our lives

In Jiakuang Majia village, there is no artificial intelligence, algorithm or other cutting-edge technology involved – it all boils down to pieces of paper and tedious manual labour.

“It’s a lot of work,” Yang, the information gatherer, said. “I’ve been kept so busy that I don’t have time to work on the farm any more.”

Every month, she tallies up everyone’s scores on a single sheet using an old calculator. Little red stars and flags are then assigned to villagers’ names on public bulletin boards, with one equalling one star and six stars adding up to a flag.

Fifteen minutes’ drive away in the urban heart of Rongcheng, few people on the streets have even heard of the social credit system or their credit score – even though the government has spent the last seven years establishing and promoting it.

The city ranks residents from AAA to D based on their personal scores. Every adult resident, including migrant workers, starts with 1,000 points, and there are more than 200 ways to gain or lose points.

My face is the best credit. The government’s rating is merely a gesture on paper

Points are added for volunteer work, donating blood, reporting counterfeit products and attracting investment to the city. Points are lost for breaking traffic rules, breaching family planning policies, flouting contracts and evading tax.

“Triple As” are rewarded with small benefits like free medical check-ups, 30 cubic metres of free water a year, a 300-yuan discount on heating bills and concessions on bank loans. “Ds” lose access to government subsidies, are barred from applying for government jobs or bidding for government tenders and face loan restrictions, among other punishments.

This all-encompassing score is supposed to permeate and shape all aspects of lives in Rongcheng – only that it hasn’t, at least not yet.

“It is just part of the government’s usual propaganda. It has nothing to do with our lives,” said Zhou Wen, a taxi driver in his 40s.

Is someone in debt nearby? Chinese court uses app to alert people as part of social credit system

Public notice boards explaining the system or displaying model high scorers are common, but few seem to take any notice.

At First Morning Light, a gated community touted by the government as a social credit success story, a young man running a convenience store opposite one such noticeboard has little interest.

“It’s for those old retirees who have nothing much to do every day,” he said.

At the Rocky Island agricultural products market, Liu Huayang’s cooked meat store is one of five shops awarded a five-star integrity rating in 2017 – the highest possible ranking in the market’s own social credit project.

There was no follow-up from the market’s management office and shop owners quickly moved on.

The general public may not know about it, but we public servants do know. It does have a binding effect on us

“My face is the best credit,” Liu said. “The government’s rating is merely a gesture on paper.”

But elsewhere in the city, some people are taking note, particularly those who work for the government, public institutions and state-owned companies.

In the lobby of Rongcheng People’s Hospital, senior staff member Wang Shuhong said she drove more carefully now because traffic infringements cost not just money but also social credit points.

“Many from the general public may not know about it, but we public servants do know. It does have a binding effect on us,” she said.

According to Wang, applicants must have a ranking of A or above to be hired for permanent positions at public institutions. For contractors, such as security guards, B is a minimum.

Drones, facial recognition and a social credit system: 10 ways China watches its citizens

The system is also evident at Rongcheng’s city hall, where two machines print out credit scores, mostly to people applying for home loans. One man said he needed the score to get government funding for an entrepreneurship programme.

But most did not think much about the system or their score, treating it as just another bureaucratic hurdle.

Even regulations [that] are seemingly apolitical can be made political when the Communist Party of China decides to use them for political purposes

“Banks want to know your ability to repay a loan,” he said. “A unified social credit score would simply not be the right data to help them make the decision they need to make.”

Daum said scores were just propaganda to promote a culture of trustworthiness – whereas blacklists were the real enforcement tool.

Regulatory and oversight bodies covering various industries and areas have drawn up a series of blacklists of serious offenders. Those who don’t comply with laws and regulations can face punishment from multiple agencies in dozens of areas, from food safety and environmental protection to tourism, taxation, e-commerce, finance and real estate.

China to bar people with bad ‘social credit’ from trains, planes

The best known of these blacklists is the Supreme People’s Court’s roster of people who have failed to comply with court judgments.

The defaulters face broad consequences – they can be barred from taking flights and high-speed trains, staying at luxury hotels and enrolling their children in expensive private schools.

By the end of last year, defaulters had been blocked from buying a combined 17 million airline tickets and 5.4 million high-speed rail tickets, according to the National Development and Reform Commission, which leads the work in building the social credit system.

Damage control

The social credit system is designed to solve many real problems in a country still riddled with fraud, counterfeit products, and food safety and public health failures.

But the system could also be used to reinforce political control.

For example, while the blacklists relate to violations of existing laws and legal obligations, it does not mean those legal requirements are justified, Daum said.

“If the underlying offences and laws are unjust, like limitations on speech or religious practice, then their enforcement just doubles down on that,” he wrote in a blog post.

In addition, some serious charges, such as “endangering national security”, are extremely broad and purposefully vague, enabling them to be applied arbitrarily.

Samantha Hoffman, a non-resident fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said this was because there was no genuine rule of law in China.

“Even regulations [that] are seemingly apolitical can be made political when the Communist Party of China decides to use them for political purposes,” Hoffman said.

“How do you know a court judgment is fair in the [party’s] legal system, which priorities the party’s political security? The answer is you don’t.”

For Hoffman, the main function of the social credit system is to make the party’s political control inseparable from the country’s social and economic development.

“If the party were genuinely interested in problem solving, it wouldn’t need social credit to do it, it would simply need a functioning civil society and rule of law,” she said.

Rongcheng’s social credit system has already incorporated elements of political control.

In July, the government released a detailed regulation on credit management for petitioners. Petitioning is a process by which the disenfranchised make a last-ditch appeal to higher authorities for help after their own governments have repeatedly failed them.

Petitioning has a long history in China and is a headache for local governments, which have resorted to brutal measures to prevent petitioners from reaching Beijing. These tensions erupted in Rongcheng in 2012, when a villager who had been stopped from petitioning set off a home-made explosive in a local government building, killing himself and wounding six others.

Under the July regulation, petitioners who do not follow “procedures” can be stripped of points or downgraded.

Petitioners who plead their case near the site of big meetings at the central or local government level will have 50 points deducted, while petitions mounted in “sensitive areas” in Beijing result in an automatic D ranking. The same applies for petitioners who “make trouble” and “get used by the internet and foreign media”.

The new rules have already hit its first victim. Last month, a petitioner surnamed Gao lost 950 credit points and his rating plummeted to a D after sending more than 1,000 online letters appealing for help with his mother’s two-decade-old medical dispute.

According to a rule that deducts 10 points for “using the online petition system to repeatedly complain in spite”, he lost 950 points for doing it 95 times in the three weeks after the rules came into effect.

Back in Jiakuang Majia village, Yang keeps track of the points for her corner of the village.

According to her, nobody has lost any points for bad behaviour since the programme got rolling a year ago. “It’s more about promoting positive energy,” she said.