China’s extradition requests must be based in law, not on persuasion

- Beijing’s pursuit of fugitives overseas is rooted in President Xi Jinping’s call to end ‘avoidance paradise’, but bringing them home is not straightforward

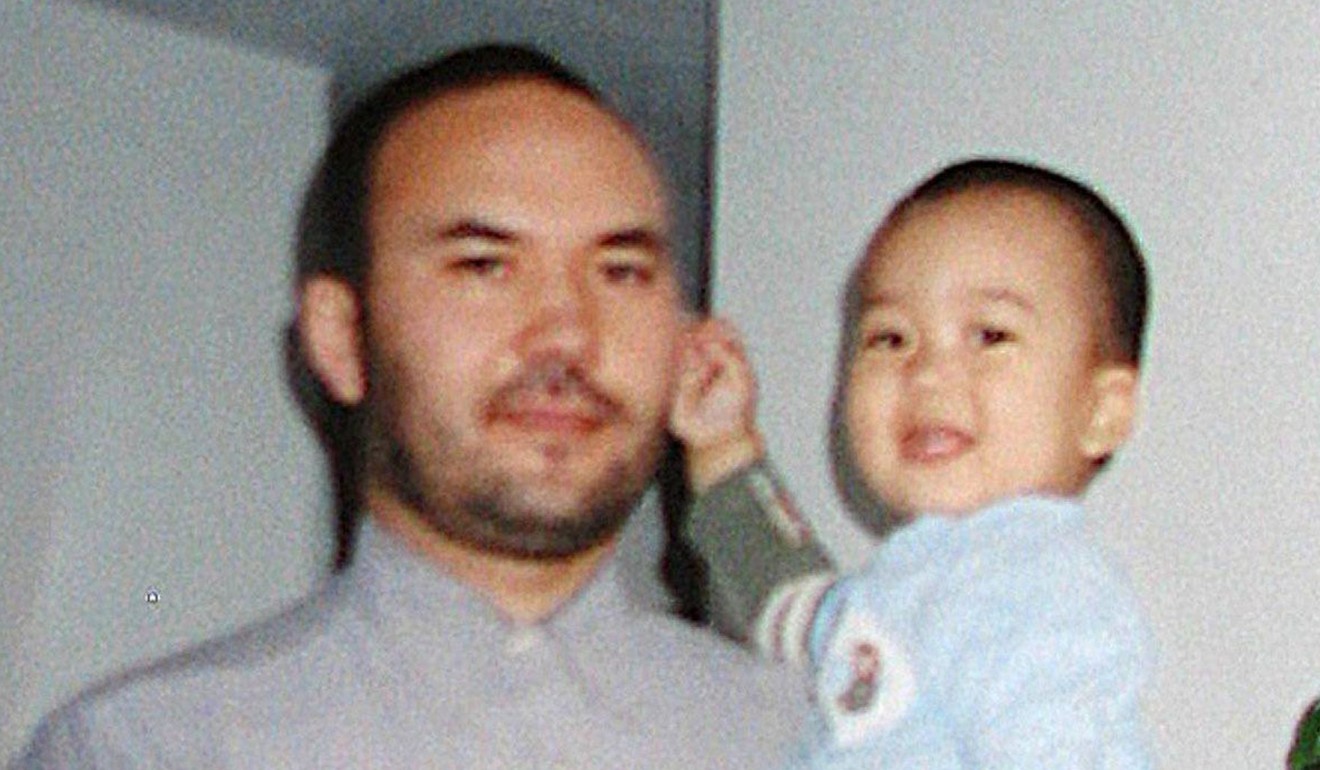

In March 2006, Huseyin Celil, a Canadian citizen who was visiting Uzbekistan, was arrested by Uzbek police. The Canadian government requested Celil’s release and return to Canada, but the Uzbek government deported him to China. In November 2006, he was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment for terrorism.

The case did not attract a great deal of attention outside Canada, perhaps because Celil was born in China, and China claimed, unconvincingly, that he was a Chinese citizen. It served as an example of what may be a growing trend: the extradition of non-Chinese citizens to China.

China’s aggressive pursuit of fugitives overseas goes back to early 2014, when President Xi Jinping said: “You can’t let foreign countries become the ‘avoidance paradise’ for corrupt elements.”

Communist Party Central then set up the Central Pursuit Office, which is supported by staff from several ministries, including the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the police, the Ministry of State Security, and the People’s Bank of China.

The office gave catchy names to its operations, such as “Fox Hunt” and “Sky Net”. It stated that it used four methods to get hold of suspects overseas: extradition, the forced repatriation of illegal immigrants, overseas litigation, and “persuasion”.

Extradition is the gold standard, from China’s point of view. China initially was able to sign extradition treaties only with less developed countries such as Uzbekistan, but as its status improved, so did the number of treaties, and recently it has concluded treaties with Italy, France and Spain.

These treaties have been in operation for only two years or so, and there is little case law. Yet in nearly all cases, the debate surrounding such treaties focused on whether it was right to send fugitive Chinese citizens back to China.

Little or no attention was paid to the possibility that third country fugitives might also need to be deported.

Similarly, a fierce debate in Australia on the morality of an extradition treaty with China concluded that it was not possible to safeguard the human rights of those sent to China, and therefore it was better to rely on case-by-case reviews to see whether deportation without treaty would be possible.

The UK, the US and India have no extradition treaties with China. Westminster is even doubtful about those it has signed with other countries, and the House of Lords set up a commission in 2015 to look into how they were used.

The chairman of that committee, Lord Inglewood, said: “We recognise many of the concerns about the US justice system, particularly lengthy periods of pre-trial detention and difficulties in obtaining bail.”

Given this attitude to the procedures of an ally, it is extremely unlikely that any such treaty could be reached with China. Yet this does not let British citizens off the hook.

Vivienne Bath, a professor at the University of Sydney, commented that “the host country is able to deport non-nationals in accordance with its own laws, even in the absence of an extradition treaty, but more importantly, China can bully people into returning.”

This last point referred to what China called “persuasion”, a tactic called “quan fan”. It is controversial as it involves Chinese judicial personnel travelling overseas – having located the fugitives – and convincing them without coordination with police or government in that overseas country to return to China for trial.

It was illustrated in surprising detail in the 2017 TV show In The Name of the People. The character Ding Yizhen, a corrupt official, escaped to the US where he lived the life of a lowly caretaker, and one episode featured investigators sent to take him back.

In real life, the investigators do not always get their way. An individual who had obtained US citizenship and lived in Chicago was targeted in this way by investigators who attempted to persuade her to return to China.

The information they used was incorrect and therefore ineffective on her. She eventually complained to local police, citing harassment, and the “persuasion” ceased.

The job is easier in countries where there is an extradition treaty, but even then, the offence in question must be an offence in the country where extradition is sought.

Extraditions are part of a three-piece suit for anti-crime cooperation across borders. The other two components are mutual legal assistance treaties and prisoner exchange.

Hong Kong plans to make it possible to extradite criminals to mainland China. This, too, brings with it the risk that people passing through Hong Kong could thus be detained for political or commercial reasons.

Nicolle Liu, of the Financial Times, pointed out that the suggested changes would allow Hong Kong’s chief executive, who is appointed directly by Beijing, to issue arrest certificates.

In the popular imagination, this would mean legitimised re-runs of the 2015 case in which five Hong Kong vendors who sold politically sensitive publications vanished. All of them reappeared in China, claiming that they went voluntarily to assist with an investigation.

Chinese media has reported all successful extradition cases. For example, the case of Yao Jinqi, described by the China Daily as “the first former civil servant extradited to China from a European Union member state” – in this case, Bulgaria. He moved to Bulgaria in 2005 and was extradited in November last year on charges of corruption.

How likely is it, then, that a non-Chinese citizen could be extradited to China? Unlikely, at present. All extradition treaties give each signatory nation the right to protect its own citizens.

China would not extradite its own citizens overseas, and foreign countries would not extradite their citizens to China. This leaves third country citizens that happen to be in the treaty counterparty – like the Canadian who happened to be in Uzbekistan.

There are safeguards: the principle of speciality stipulates that an extradited individual can be tried only for the offence, or offences, specified in the extradition request, unless the surrendering country or the extradited individual has given consent.

An offence warranting extradition must be proscribed in both China and the other country. So, for example, you should not be extradited from Spain to China unless the crime you are accused of is a crime in Spain.

And there are various other protections, against accusations of political crimes and against discrimination with respect to race, religion or nationality.

Sabrina Choo, of the Singapore Attorney-General’s Chambers, author of one of the most detailed overviews of China-related extraditions, has argued that the use of deportation, in lieu of extradition, to return fugitives “may disincentivise China from providing safeguards or reassurances on the treatment of fugitives upon their return,” because the process can and has been used to circumvent an otherwise accepted ground for denying the return of a fugitive to a requesting state.

In practice, however, we do not yet know how extradition requests from China will be handled, as they are so rare.

Perhaps it is political and economic power that will set the standard for extradition of foreign nationals to China, rather than the force of law, and we will soon see a British, Indian, or American citizen being extradited from France or Spain for trial in China.