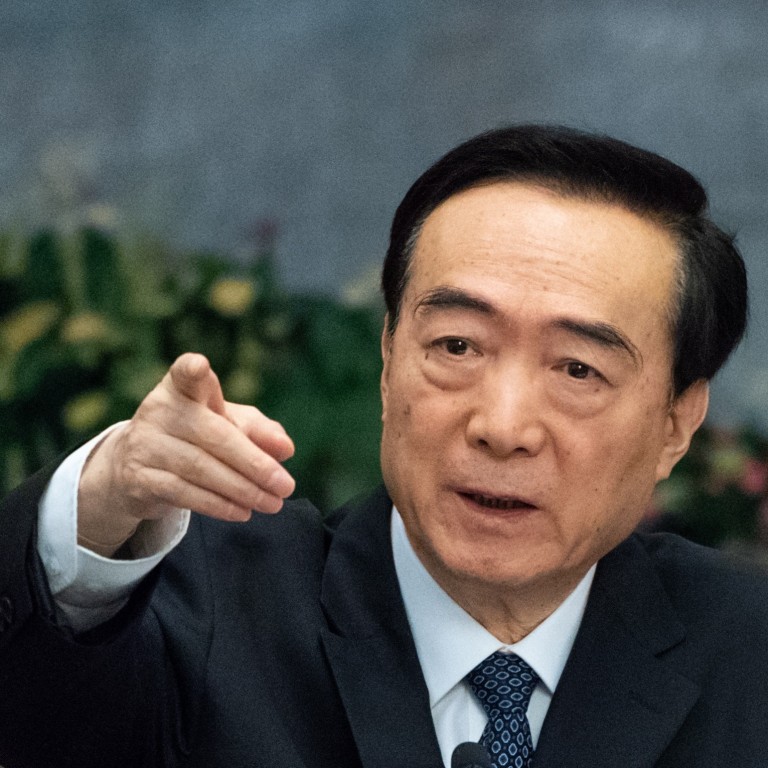

Architect of China’s Muslim camps Chen Quanguo expected to stay on in Xinjiang for now

- Party boss behind clampdown in far western region believed to be in line for promotion, but source says ‘a change in leadership is unlikely’

- Despite international criticism, ‘Beijing sees that Chen is doing a good job in Xinjiang’ where stability is a priority, according to observer

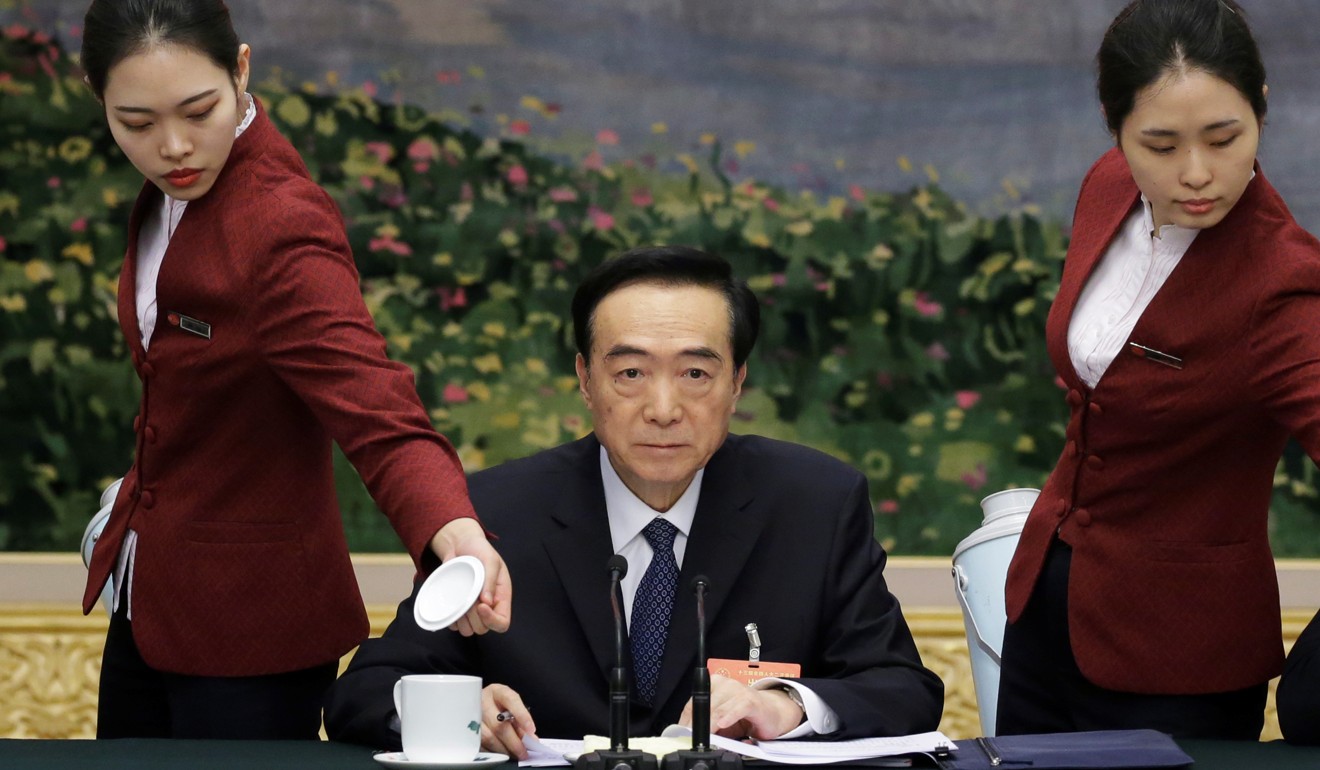

When Xinjiang officials took questions from the media recently about the crackdown in the western border region, it was the chairman, Shohrat Zakir, who did much of the talking.

But for the reporters in the room and the China watchers observing the event via television broadcasts around the world, there was no question of who was in charge.

“The [policy] direction has been set,” one of the sources said. “The overriding priority in Xinjiang now is to maintain stability – a change in leadership is unlikely.”

Beijing has drawn international condemnation for its mass internment camps in Xinjiang, where human rights experts estimate 1 million or more Uygurs and other Muslim minorities have been held for political indoctrination. The government insists they are “vocational training centres” needed to counter “religious extremism” and ensure stability. Chen has driven the campaign, and observers said Beijing was unlikely to make leadership changes in Xinjiang while it is under pressure over the repressive policies.

Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in California, said Chen was not likely to be promoted to the upper echelons in Beijing in the near future because “all the other key positions that would be considered a promotion are occupied with people unlikely to retire soon”.

He added that Chen’s next “upwards move” would probably be to the powerful Politburo Standing Committee, which was unlikely to happen before 2022.

Alfred Wu, an associate professor with the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, agreed that the president was unlikely to make changes to the Xinjiang leadership at the moment. He said Xi would want to keep Chen where he was since he had proven to be effective at keeping the region “under control”.

“Chen understands stability is what the top leadership wants and he is able to deliver results,” Wu said. “Despite criticism by Western governments, Beijing sees that Chen is doing a good job in Xinjiang – although the real question is about stability in the long term.”

Another source familiar with Xinjiang affairs said the clampdown under Chen stemmed from policies set out by Xi at a work conference in 2014.

“The overall direction was set by Beijing and the leadership in Xinjiang was entrusted to turn those policy directives into operational details to be implemented,” the source said.

He added that it was decided at the conference that “maintaining long-term stability” was a priority.

“Stability is the primary focus and developing the economy takes second place,” the source said. “This will continue to be the priority until the top leadership reviews its Xinjiang policies again.”

That focus has seen Chen take a draconian approach to governing the region – setting up grass-roots vigilante cells to stamp out any sign of dissent among Uygurs and other Muslim minorities.

A source with family members working for the Xinjiang government said some of the measures introduced in major cities like Urumqi would soon be rolled out elsewhere in the region.

One of them has involved coordinating small shop owners to keep watch for “destabilising” activities in their neighbourhoods. “About 10 shopkeepers work together under a team leader chosen by the district chief or local police boss, and they’re checked on regularly to make sure they are guarding against ‘terrorists’,” the source said.

“They have to pay for their own anti-riot gear – helmets, protective vests, batons – and they get training two or three times a week,” the source said. “It’s quite a scene seeing young police officers directing a team of elderly shopkeepers in drills pursuing imaginary terrorists.”