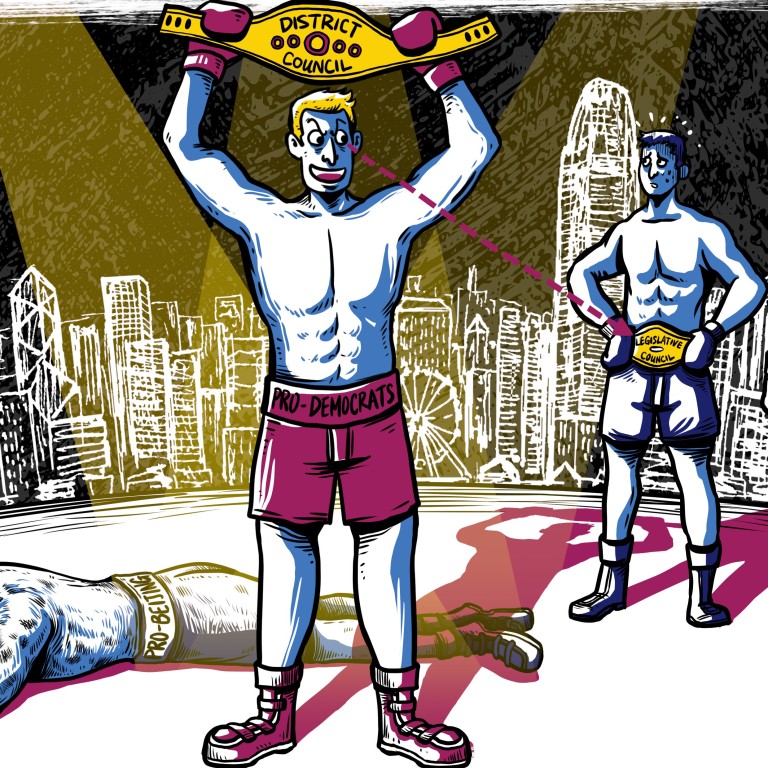

Why Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing camp may have to get used to losing

- Half a year has passed since the city erupted into turmoil, exposing divisions over its future.

- In a new series, the South China Morning Post looks at the road ahead for Hong Kong and the challenges its people can expect to face.

“So [the landslide win] by the opposition has effectively ushered in a political process through which [the opposition] would be able to seize power through elections and that would soon trigger a security crisis for the one country, two systems,” said Tian, who has advised China’s leaders on Hong Kong affairs.

The pro-establishment camp ran hard in the district council elections, but they were badly punished in an unusually high turnout of voters that left them with 42 per cent of the vote, suggesting they would lose support in September, he said at a seminar in China’s capital early this month.

It was clear the pro-Beijing camp would face an uphill battle in the next Legco elections, said another mainland expert on Hong Kong affairs at the same seminar, who spoke on condition his name would not be used. He added that pro-Beijing candidates went into the district council elections with all the advantages in terms of resources and experience, but they failed to turn that into winning votes.

Ip was as a rising star of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), the biggest pro-government political party in the city. He is one of many councillors unseated by a surge in support for pro-democracy candidates that took 392 out of 452 seats in a major restructuring of grass-roots councils across Hong Kong.

“From the moment I submitted the form to run in the election, I knew it would not be an easy race because of the current political atmosphere,” Ip said. “So my mood and emotions have not been too down or fluctuated too much. I knew it would be hard.”

With the loss of the seat, Ip also loses the government-paid monthly subsidy for district councillors, which he said would limit the work he could do for the community. But he said the DAB was regrouping and residents had offered their continued support for him.

For the winners, the process now was to begin solidifying support and expanding political influence, said Wu Chi-wai, 57, leader of the Democratic Party and one of the biggest gainers in the district elections. He said winning was just the first step on a long road to full democracy.

“This district election shows that the central government needs to face the demands of a democratic system,” he told the South China Morning Post soon after the election.

What were voters in Hong Kong district council elections saying?

Clarisse Yeung Suet-ying, 33, was re-elected for the Wan Chai district, but this time around she’s back with five first-time winners from her pro-democracy alliance, Kickstart Wan Chai.

Yeung said she was eager to deliver quick changes to the community and restructure the system.

“We have to figure out ways to fundamentally change the suppressive rule-making process of the district council that was overwhelmingly pro-government in the past,” she said.

However, while the pro-democracy camp won big in the local elections, it still had a lot of work to do to expand its support base beyond the roughly 60 per cent of voters it had now, she said.

“Therefore, this will make grass-roots level work all the more important,” Yeung said.

Though district councillors have limited authority and spend much of their time on issues directly related to their community, political analysts said they could have a profound influence on future elections for Hong Kong’s chief executive.

Hong Kong elects its chief executive through a committee of 1,200 members. Pro-democracy groups look set to take all 117 seats on the committee set aside for district councillors, adding to the 300 or so members of the pro-democrat bloc on the committee.

In terms of sheer numbers, that left the democrats a long way to go, but it also represented a shift in public sentiment that might have a profound bearing on the election of the next chief executive in 2022, said Gu Su, a political scientist at Nanjing University.

He said the landslide victory in the district elections had given pro-democrats the confidence that they had the public’s strong support, so their political aims and ambitions were also higher.

Why was China’s domestic security chief Guo Shengkun at Carrie Lam’s meeting with Xi Jinping?

“The pan-democrats might have less than half of the seats [on the committee], but it’s already a big boost and source of encouragement for them,” Gu said. “If they can influence the pro-Beijing camp and gain 100 more seats, then they will have the deciding votes to nominate the chief executive, which would be a very big problem for Beijing.”

Lau Siu-kai, vice-chairman of the Hong Kong-based Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, does not believe that will happen.

Beijing had the ultimate control of Hong Kong and would not allow Legco to be controlled by politicians who did not toe its line, he said. Such an outcome would turn Hong Kong into a city that might threaten national security, he said, declining to elaborate on what action could be taken.

Meantime, Hong Kong has become a front line in the growing conflict between the United States and China for global influence and control.

Zhu Feng, a professor of international relations at Nanjing University, said Beijing was clearly concerned about the growing influence of the local pro-democracy movement and what it saw as overseas meddling in Hong Kong affairs.

“Western countries have business interests in Hong Kong, and they see Hong Kong’s human rights and freedoms as their responsibilities,” he said. “But for Beijing, stability in Hong Kong is the issue and it won’t make any compromise on that.”

What went right or wrong in district council elections for winners and losers

But observers said the confrontation between China and the US was only likely to increase in the coming years, especially with Washington labelling China a competitor and a potential security threat to the US.

Wei Nanzhi, an associate researcher at the Institute for American Studies of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences based in Beijing, said Hong Kong was being used by Western countries especially the US, to retaliate against China and this situation was not likely to change soon.

Tian at Beihang University echoed the view, seeing Hong Kong as a football in a clash between two global powers.

“Hong Kong will become a place for competition and constant struggle for a long time as the city’s younger generation comes through and new cold war between China and the West deepens,” Tian said.

He said the Communist Party laid out in October a set of clear guiding principles on how to deal with Hong Kong but the challenge would be to implement them.

Lau Siu-kai in Hong Kong said Beijing was now focused on following through with those principles and part of that was strengthening the bonds between the Hong Kong government and the “patriots” or pro-Beijing politicians.

Another piece of the puzzle from Beijing’s view was tighter control of the mechanism to appoint the chief executive and making more use of the constitutional power of the National People’s Congress, China’s legislative body, over Hong Kong, Lau said.

“Beijing won’t allow Hong Kong to become a threat to its national security or a subversive base that foreign powers can use to wrestle with China.”