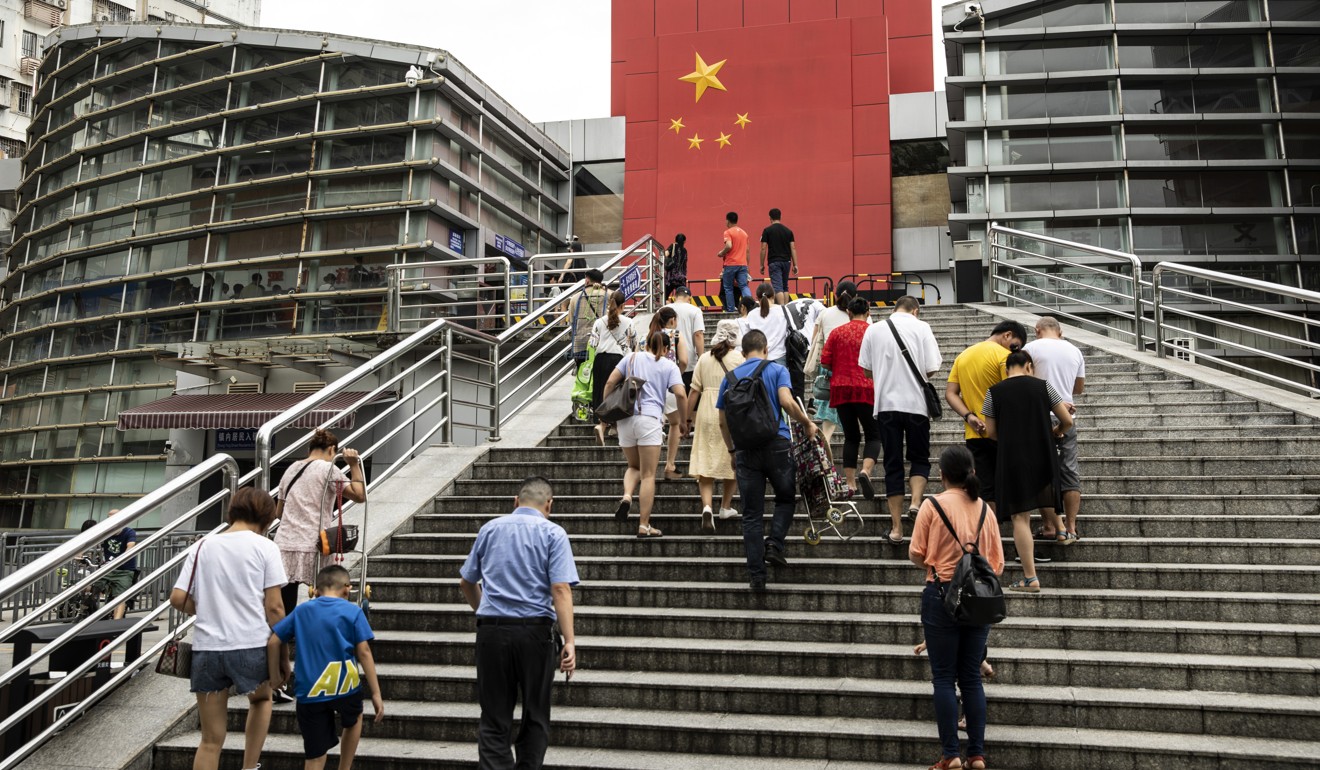

Hong Kong unwelcome mat means city’s loss as mainland Chinese look elsewhere

- Half a year has passed since the city erupted into turmoil, exposing divisions over its future

- In the fifth part in a series on the road ahead, the Post looks at how life has changed for mainland Chinese living, studying and working in Hong Kong.

Inevitably, the mainland Chinese that live, study and work in Hong Kong got the message that they are less than welcome. Many of them say they have been getting that message for many years.

Mainland drifters

A more recent wave of arrivals from the mainland are educated young professionals, referred to as gangpiao in Mandarin, which translates roughly as “drifters” to show they don’t have roots in Hong Kong.

There is no official data on the number of gangpiao, but a Hong Kong census in mid-2016 indicated about 77,000 China nationals fit the demographic – they had lived for several years in the city, around 80 per cent were aged between 18 and 30, and more than 60 per cent held postgraduate qualifications. In other words, just the sort of fresh talent Hong Kong needs to attract as its own population ages, but is now in danger of losing.

Many of the gangpiao – such as David Feng, a PhD student at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) – came to the city seeking opportunity; also drawn by shared culture and a social tolerance. Those attractions faded fast in the anger and tear gas that characterised Hong Kong in the second half of last year.

“My heart aches and I am really disappointed to see the city descend into a place that’s highly politicised and not suitable for study and research any more,” said Feng, who started his doctoral studies from September in computer science. Hong Kong was once a place where people got along regardless of place of origin, he said.

Feng explained that he completed a master’s degree at Loughborough University in Britain in 2017 and carried a Chinese national flag during his graduation ceremony and nobody cared. In November, at a graduation ceremony at HKUST, he said he tried to distribute some small Chinese flags to other mainland students, but was advised by a campus guard that it was dangerous. Feng said some local students threatened him.

“I never imagined that I would encounter this in China’s own territory,” said Feng, who added he doesn’t see much of a future in the city post-graduation, which isn’t good news for the economy.

Another marker is jobs. China’s government claims to have created about 13 million new jobs in urban areas each year on average over the last five years and kept unemployment largely under control at around 5 per cent, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

In the first 10 months of 2019, China created 11.93 million new urban jobs across the country, while the unemployment rate in urban areas dropped 0.1 percentage points to 5.1 per cent in October, mainly due to the improving employment for graduates.

‘Feeling unsafe’

For drifters feeling fearful on Hong Kong’s streets, expanded opportunities at home and abroad are creating a trend where some are giving up on the city, said Zhu Jie, a Hong Kong affairs expert at Wuhan University in central Hubei province.

Without enough communication and exchange, misunderstandings are bound to arise

“The loss of those people is like a bridge broken between China’s mainland and Hong Kong,” Zhu said. “It has damaged relations as the anti-Chinese acts in the past months have severely eroded trust between the two sides,” he said. “Without enough communication and exchange, misunderstandings are bound to arise, which will fuel nationalist sentiments in both the mainland and Hong Kong and make it more difficult to solve problems.”

Hongkongers living in mainland China say safety and friendships are on the line

Other professionals from mainland China in Hong Kong don’t see going back home as the only option.

Zhang Ning, 35, lived in the city for eight years, working in the civil aviation industry, as did her husband. That was until November, when her husband took a job in Toulouse in southern France.

“However, the relations between mainlanders and Hongkongers are now so hostile. It’s like a wound, even after it heals, it will leave a scar,” said Zhang, who added that the move to Toulouse meant she gave up her own job and now looks after her family.

The violence at HKUST coupled with already rising anti-Chinese sentiment on the campus led to scores of mainland Chinese students fleeing the city along with Feng. His plan now was to graduate and then look for work in his hometown in northern China or Beijing, where opportunities had significantly expanded, he said.

Zhang Jian, a Hong Kong affairs expert with the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, said the clashes in the city and the backlash had left mainlanders feeling like the walls were closing in.

“It narrowed the space where mainlanders in the city can manoeuvre as they might be reluctant to do anything that might promote closer relations between the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong,” Zhang said.

City University professor James Sung Lap-kung agreed, saying it was a shock for mainlanders to realise the scale of the sweeping negative views towards China among the city’s younger generations.

However, people could get over shock and Hong Kong remained competitive in finance, trade and business – and that attracted talent from all over the world, including the mainland, Sung said. On that point he’s backed up by the “Global Competitiveness Report 2019” from the World Economic Forum. It ranked Hong Kong third after Singapore and the United States from among 141 economies surveyed.

Meet the mainland Chinese who are living in fear in Hong Kong

However, the survey closed in March 2019, or before universities in the city were hit by protests that effectively shut down many of them for months.

Broader horizons

Interviews with others in the gangpiao grouping about a future in Hong Kong point to a mixed outlook.

Eric He, 31, a mainlander and a salesman in a Chinese-owned securities company, has lived in Hong Kong for more than nine years and hopes to stay. “A lot of friends say drifters like me have to leave and return to the mainland as soon as possible due to the crisis here, but I still think Hong Kong is a place I love, a place that has good public order, future prospects and valuable wilderness to explore. I don’t want to waste the nine years I’ve spent here,” He said.

Jing Fang, a master’s student at Baptist University, said she hoped to find a job in Hong Kong next year to gain work experience outside the mainland. “My relatives back in the mainland are really concerned for my safety here, but I don’t think the situation in Hong Kong has become that unbearable,” Fang said. “And I respect Hongkongers’ insistence to make their voices heard.”

Hong Kong-based newspaper columnist Johnny Lau Yui-Siu said blaming the unrest for why some mainlanders were leaving missed the bigger picture.

“There are always people coming to Hong Kong and leaving Hong Kong, and these choices are made considering a series of factors including career opportunities, educational background and family needs,” Lau said. If mainlanders develop skills in Hong Kong that open up opportunities elsewhere then they may leave, he added.

Geng Chunya, president of the Hong Kong Association of Mainland Graduates and a permanent resident since 2001, said he had noted a shift in attitude among the city’s mainland residents in recent years and it fitted right into the gangpiao mould – footloose and with broader horizons.

More students now graduated from universities in Hong Kong and went straight back to the mainland because they had a much more mobile mindset when looking at opportunities, Geng said. The 2019 protests were more of a catalyst, he said.

In that respect, “Hong Kong’s relative decline in quality of life, cost of living and employment choices are the main factors for them leaving”, Geng said. “The unrest in the past year, in my eyes, is not the fundamental reason.”

Read the first part in the series, on the implications of the pro-democrats’ landslide win in the district council polls, here, the second part, on the city’s role as a gateway to mainland China, here, the third part, on the risks and rewards for foreign professionals in Hong Kong, here, and the fourth part, on the youths whose lives have taken a dramatic turn, here. The next part in the series looks at the road ahead for the city’s civil servants.