Coronavirus: Chinese writer hit by nationalist backlash over diary about Wuhan lockdown

- Award-winning novelist and poet Fang Fang accused of fuelling Western criticisms of China’s handling of the Covid-19 outbreak

- Her Wuhan Diary, first published online, is now set to be released in both English and German

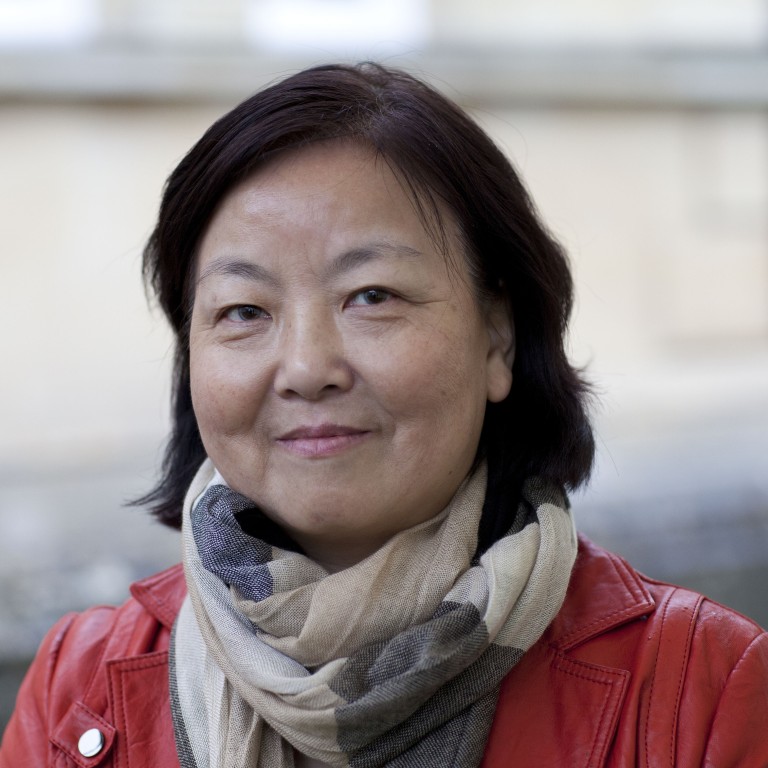

Fang Fang, an award-winning poet and novelist, was called a traitor after it emerged that her book, simply titled Wuhan Diary, would be published in English and German. Observers said the controversy reflected the rising nationalism in mainland China, especially among the younger generations.

Fang began writing her diary on January 25, just two days after the central China city in which the coronavirus outbreak was first identified, was put under lockdown.

In it she describes the difficulties of life in quarantine, as well as the spread of the disease and how it wreaked havoc, taking lives and breaking up families and homes.

Her work quickly attracted a large following but she also came under heavy fire, with people accusing her of betraying her country and trying to stir up trouble by giving China’s critics ammunition with which to attack it.

He Weiheng, a 19-year-old university student in Beijing, though critical, was more concerned about the authenticity of the translations than Fang’s writing.

“If the content of the diary is real, it is reasonable to write it and publish it,” he said. “But if the diaries have been translated without guaranteeing the authenticity, some people in China are concerned the book will have a detrimental impact on our national image and national interests.”

Another social media user composed a rap, containing some of Fang’s own words, which accuses her of trying to be a spokeswoman for the truth and influence public opinion.

“What kind of person keeps a diary on the internet,” it said. “She puts every word into the national scars.”

It goes on to say that China’s young people will shoulder the responsibility of developing a strong nation.

Despite the online criticism, Fang has also received plenty of support, from at home and abroad.

Yue Zhongyi, a 63-year-old resident of Wuhan, said a lot of the criticism represented nationalist sentiment rather than the views of the city’s people.

“I asked all of my neighbours and friends and all of them said they support Fang Fang,” he said. “Her diaries represent our experiences and our feelings.”

The writer’s critics misunderstood the notion of patriotism, he said.

“Everyone loves his country, but the country and the government are two concepts. If someone criticises the government, you can’t say that person is a traitor.”

US publisher Harper Collins said an English-language version of Fang’s diary would be available for sale online in June, while Hoffmann and Campe will publish a German-language version.

While some have been quick to criticise Wuhan Diary, the Chinese government and Communist Party have been more restrained, with only a handful of state media commentators expressing an opinion.

Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of the nationalistic tabloid Global Times, urged people to respect the sentiments documented in the diary.

“[We] should not exaggerate their meaning, nor should we amplify the significance of the diary as well as the resonance it draws [from the public],” he said last month on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like platform.

Wu Qiang, an independent political analyst based in Beijing, said the coronavirus pandemic had created a schism, with nationalism at its core. Despite the country now being the world’s second-largest economy, some people were still haunted by China’s past humiliations at the hands of foreign forces and felt they must rise up to defend their country, he said.

“These young people are still sharing the thinking and ideas of conservatism, xenophobia, and being easily offended,” Wu said.

But the attack on Fang’s work might also be an attempt by China’s authorities to divert the public’s attention away from an in-depth reflection on the outbreak, he said.

“Channelling people’s attention into nationalistic sentiment can effectively offset people questioning what is the real social justice after such a severe disaster.”

Also, despite the backlash she had faced, Fang – who is a former president of the officially affiliated Hubei Writers’ Association – was still considered a “politically trustworthy figure”, Wu said, and her work was still available on China’s internet.

“Many voices from Wuhan have been silenced. The fact that her work was allowed to survive is the art of censorship: to let out a relatively moderate voice to avoid the embarrassment of a completely blank canvass,” he said.

In an interview with the Chinese social media account Scholar, Fang said it was childish to describe publishing the book overseas as an act of treason, and called for greater tolerance.

“There is no tension between me and the country,” she said.