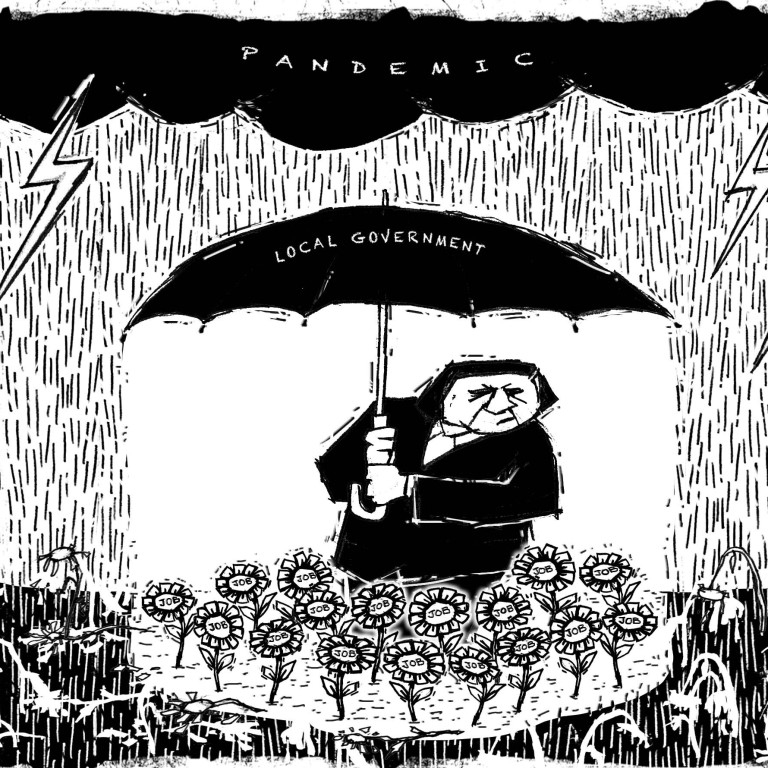

China’s local officials under pressure amid coronavirus pandemic to address rise in unemployment

- Chinese leadership prioritises keeping unemployment numbers down as soaring jobless rate threatens social stability

- Policies include incentives aimed at those most at risk – graduates, migrant workers and the small business sector

This is the third in a series of six stories exploring the causes and consequences of the domestic unemployment crisis China may face following the coronavirus pandemic. This story looks at the switch in focus from growth to keeping the country’s jobless rate under control.

“As members of the Chinese Communist Party, we must seek happiness for the people wholeheartedly … and do everything we can to help poverty-stricken families to move into new homes and provide training for them so they can find jobs and live a happy life,” Xi told a family, in the company of local cadres.

But the challenges outlined by Xi were easier said than done, according to experts. They pointed out that surplus farmhands in China’s vast countryside would have to compete with millions of urban labourers for the limited jobs available.

The slowing economy is putting businesses under pressure to make redundancies while, at the same time, a looming global recession caused by the pandemic has dimmed prospects of a quick recovery as investors and foreign buyers tighten their belts.

In February, China’s urban unemployment rate jumped to 6.2 per cent, the highest on record. In March it dipped slightly to 5.9 per cent as more businesses reopened. But the numbers are highly contested.

An April analysis by UBS estimated that 50 million to 60 million people in the hard-hit services sector may have lost their jobs or are otherwise not working, and a further 20 million people in the industrial and construction sectors may be in the same position.

China’s unemployment rate could reach 10 per cent this year, resulting in at least an additional 22 million urban workers losing their jobs, according to a report by The Economist Intelligence Unit on April 22.

Hu Xingdou, a Beijing-based independent economist, said China’s official unemployment rate did not reflect the real picture.

“It is not possible for an individual to find out the real unemployment rate. But by observing what’s happening around us, with restaurants closing and enterprises laying off staff, we can tell the real figure must be higher,” he said, adding “this is why [this year] the central government has given employment top priority”.

Finding jobs for this year’s fresh crop of graduates has been flagged as a critical task for local officials this year. Six central government departments and Communist Party bodies launched a special campaign last week to push for more jobs for graduates – estimated to number a record 8.47 million this year.

China faces looming crisis as pandemic sends unemployment soaring

Chen Peipei, a 22-year-old student at Shantou University in the southern province of Guangdong, is one of the graduates worried about finding work. She has submitted dozens of applications in the past three months, without success. “I’m still trying my best to look for jobs but there’s a vague sense of failure in my heart,” she said.

The unemployment issue has dominated multiple government meetings over the past two months and was named as the country’s priority at the April 17 meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee, Beijing’s highest decision-making body, headed by Xi.

A notice from the Shanghai government on April 29 directed its state-owned businesses to ensure that at least half their new recruits were recent graduates.

China starts campaign to help new graduates find jobs as economy slumps

Wuhan – the provincial capital of Hubei in central China where the coronavirus first emerged – has announced a target of 250,000 jobs for graduates and is offering companies a 1,000 yuan (US$140) incentive for every graduate they hire.

But some experts have questioned the effectiveness and sustainability of measures introduced by local governments. Subsidies and exemptions for SMEs depend on local government revenues, which will also be under strain, while recruitment levels in state-owned enterprises are determined by their own, independent, accounting practices.

“Start-up companies need financial support, but big banks are reluctant to give them support,” Hu, the economist, said. “There’s little the local government can do.”

To make matters worse, the ongoing economic conflict between China and the US, along with calls in the West for an economic decoupling from China, is likely to lead to further deterioration in China’s import and export industries and the country’s ability to attract foreign investment.

“The future international market, as well as China’s relations with other countries, will have a huge impact on China’s economy,” Hu said.

“Employment is a pressing priority in China. To keep employment stable is to protect people’s livelihoods and to defend the regime,” said Chen Daoyin, an independent political analyst and a former Shanghai-based professor.

China central bank primed for stimulus boost as virus drags on economy

Rising unemployment and job losses would also undermine the Communist Party’s commitment – declared by Xi himself – to satisfy the Chinese people’s pursuit of happiness, according to Chen.

But he added that, if the government’s measures were implemented smoothly, they could be effective in preventing the convergence of new graduates and migrant unemployment that would threaten stability.

“If there were a wave of unemployment, the middle class would slip to the bottom of society while the bottom would collapse, making it impossible to fulfil people’s pursuit of happiness and the party would lose its legitimacy,” he said. “The bottom line is to ensure employment and meet people’s basic needs.”

For more than a decade, China has tried to deal with the influx of university graduates into the job market by resorting to a Mao-era campaign to encourage them to go to the countryside.

Faced with the current grim employment situation, experts predict there will be more incentives this year aimed at transforming rural areas and expanding the government’s anti-poverty programme while keeping unemployment in check.

On April 10, the government of China’s southeastern Fujian province published a plan to guide 600 graduates towards working in rural areas. Successful applicants will receive a living allowance and have their student loans covered by the local government, at up to 2,000 yuan a year.

About a month later, Guangdong province in southern China announced a similar plan, recruiting 2,000 graduates to spend two years in rural areas. It was an extension of a campaign which, by 2019, had attracted about 27,000 graduates.

Another problem for the Chinese government is that its antidote to the 2008 global financial crisis may not work this time. China escaped the great recession with a 4 trillion yuan (US$564 billion) stimulus package which left a heavy debt burden on local governments and state firms, while postponing the country’s economic transition.

Wei said that in hindsight the response to the 2008 trauma had led to chronic problems such as excessive capacity for the economy.

“This time we must focus on economic structural reform and quality of development,” he said, adding that the key point was to boost domestic consumption and improve consumption quality. Although China was facing an economic downturn, he predicted the country’s consumption growth in 2020 could still reach last year’s level of 8 per cent.

China's factory prices hit four-year low as virus pressure continues to mount on manufacturers

Not all economists are as optimistic. Liang Qidong, deputy director of the Liaoning Academy of Social Sciences, said investment was needed in areas like the construction of 5G networks, data centres, and high-speed railway lines.

“The most effective way to offset the economic downturn is investment, but the old ones won’t work, so we have [to concentrate on] so-called ‘new infrastructure’,” he said.

Liang pointed out the country’s biggest headache would be young migrant workers from the countryside, who would not be able to return to farming if they failed to find jobs in the cities. “If they can’t find a job in the city but also can’t go back [to farm] in their villages … It may lead to social unrest,” he said.

China’s small businesses are already feeling the effects of the downturn. Wu Yadi, a 28-year-old jewellery shop owner on Taobao, China’s largest e-commerce platform, said he had cut his staff from more than 40 in previous years down to a dozen, but the downsizing had not spared his business from operating at a loss this year.

There is still optimism, however, that the situation can be turned around. “Many of my friends feel gloomy about the future, but I’m confident with my ability and my team,” he said.

The fourth part of this series will examine the hopes and fears of China’s university graduates. Meanwhile, read about the scope of China’s looming jobless problem, and the delicate relationship between government and business at the heart of the country’s social welfare system.