Xinjiang: China’s white paper may point to forced labour claims, experts say

- The 1.29 million workers cited as getting ‘vocational training’ each year could be an indication of forced labour, according to researcher Adrian Zenz

- He says the document tacitly acknowledges the coercive nature of the centralised training system and transfer of surplus rural labourers

Released on Thursday by the State Council, China’s cabinet, the white paper said the regional government had organised “employment-oriented training on standard spoken and written Chinese, legal knowledge, general know-how for urban life and labour skills” to improve the structure of the workforce and combat poverty.

Beijing is under increasing international pressure over its policies in the far western region, where it is believed to have detained at least 1 million Uygurs and other ethnic Muslim minorities in internment camps.

Its white paper said the regional government provided vocational training to an average of 1.29 million urban and rural workers every year from 2014 to 2019. Of those workers, about 451,400 were from southern Xinjiang – an area it said had struggled with extreme poverty, poor access to education and a lack of job skills because the residents were influenced by “extremist thoughts”.

00:44

China sanctions US officials and Congress members in response to Xinjiang ban

Adrian Zenz, a researcher focusing on Xinjiang and Tibet, said it was the first time the Chinese government had given a specific response to allegations of forced labour through its coercive vocational training both outside and inside the internment camps.

But he said it was unlikely that many of those 1.29 million workers said to have received “vocational training” each year pertained to training linked to internment camps.

Instead, it could be an indication of forced labour, Zenz said, based on his previous research.

H&M cuts ties with Chinese supplier over Xinjiang forced labour accusations

The white paper also said the size of the workforce in Xinjiang had increased by 17.2 per cent between 2014 and 2019 – going from 11.35 million to 13.3 million.

That labour force figure for 2019 was new information, according to Zenz, who said it was not disclosed in the region’s annual development statistics report for last year.

03:47

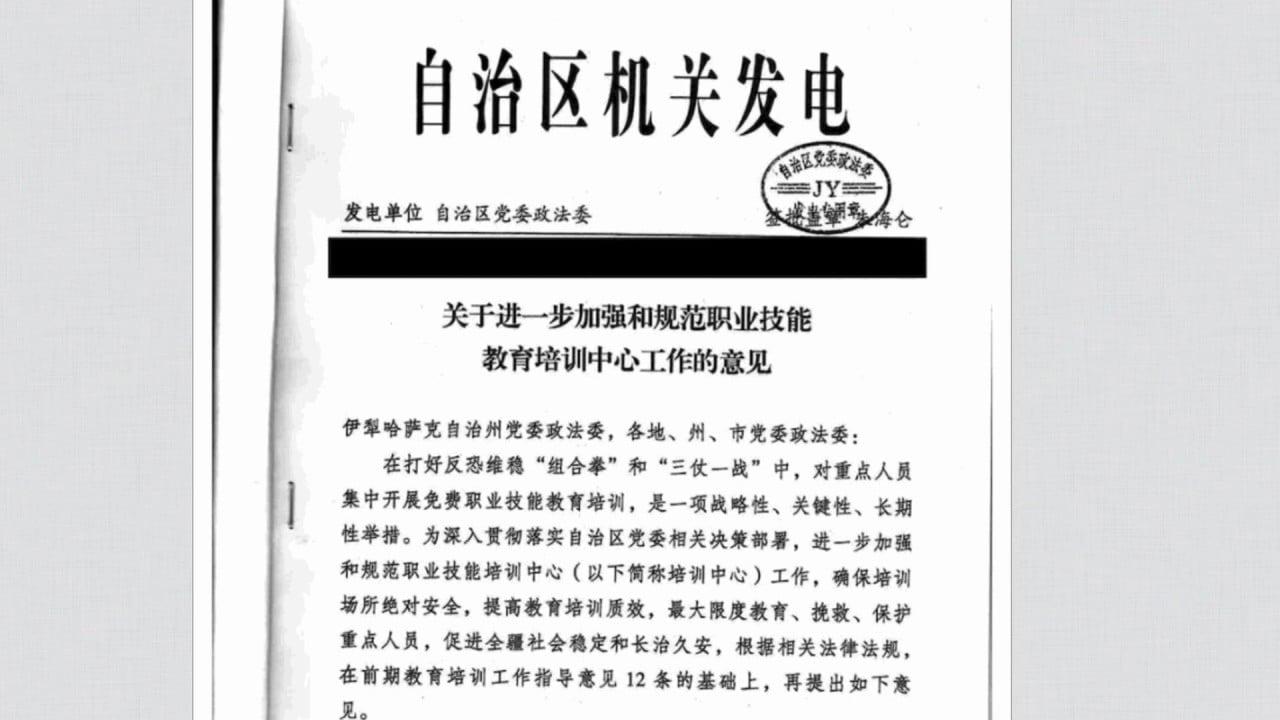

Leaked state documents describe repressive operations at China’s detention camps in Xinjiang

He also said the reporting time frame used throughout the white paper was telling, as labour force growth dropped after 2017, when the crackdown in Xinjiang began to ramp up.

“The reason they cited total labour force increase [from] 2014 to 2019 is that much of this increase took place until 2017. Increases in 2018 and 2019 were only 0.85 per cent,” Zenz said, citing China’s official economic data.

This showed a negative situation for employment overall, as many Han Chinese had left Xinjiang and business had suffered, despite claims about achievements in rural labour transfer, according to Zenz.

China invites EU leaders to ‘see real situation in Xinjiang’ amid claims of Uygur detention and abuse

He also pointed to another two figures in the white paper – the 155,000 people from registered households in southern Xinjiang who found work outside their hometowns from 2018 to 2019, compared to 221,000 for the period between 2018 and June 2020.

Zenz said the those figures would involve a significant amount of internment camp labour, as the people released from the camps were typically from poor households in southern Xinjiang.

“What’s interesting is the high share of labour transfer in 2020 – 66,000 in just six months, which is nearly the same as the average of 77,500 for 2018 and 2019,” he said.

According to Zenz, the white paper tacitly acknowledged the coercive nature of the centralised training and the transfer of surplus rural labourers.

He noted the white paper’s conclusion that, “to solve its problem of employment in the long term, Xinjiang must further optimise the industrial structure, improve the quality of the workforce, and change people’s outdated mindset”.

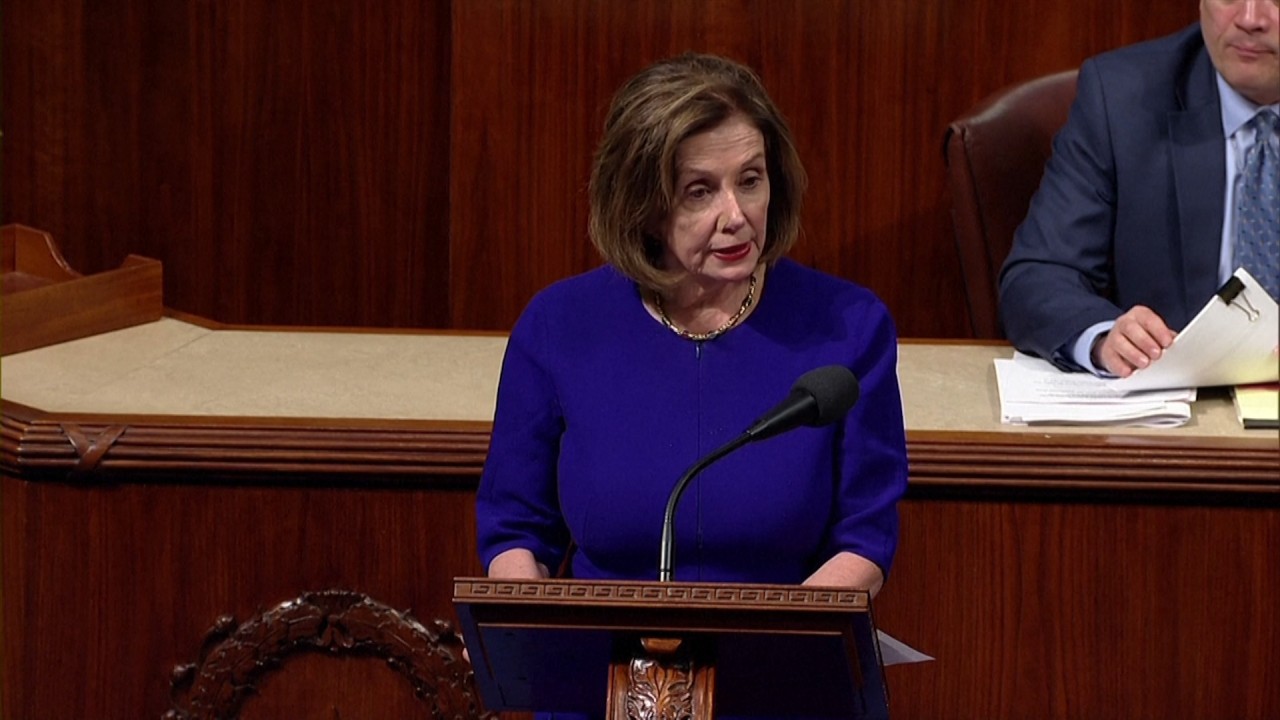

01:57

US House passes Uygur law demanding sanctions on China over human rights abuses in Xinjiang

Michael Clarke, an associate professor in political science at the Australian National University who researches the history and politics of Xinjiang, agreed with Zenz that the 1.29 million figure had a possible connection to forced or coerced labour rather than the size of the internment camps.

“However, I think it is certainly another indication of the size or scope of the efforts undertaken under the broad label of ‘re-education’,” he said.

According to Clarke, the admission that around 451,000 people from poor households in southern Xinjiang were provided with “training” was interesting as it was in line with the Communist Party’s strategy to tackle the causes of extremism in the region – such as poverty and traditional beliefs – through secular education and modernisation.

He also said that while some might see the white paper as a tacit admission of the validity of previous claims or assertions on the nature of the re-education and vocational training system, it was also clearly part of a sustained propaganda strategy to counter international criticism.

Additional reporting by Mimi Lau