China wants to be carbon neutral by 2060, but can its provinces manage it?

- Ensuring carbon emissions peak before 2030, as is promised, may prove difficult for some provinces, not least where the economy relies on coal

- Some provincial-level authorities have taken steps towards the government’s goals, while others’ actions have been slow or vague

Some eastern provinces have laid out clear climate and energy targets and included specific projects, but less developed provinces – where emissions look set to increase – were far less forthcoming.

“There is an urgent need for [the less developed] provinces to have at least milestones for diversifying their economies,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Helsinki-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

02:06

Chinese cash funds African coal plants despite environmental concerns

“It might seem now that peaking emissions later will be much easier, but if those provinces keep adding fossil fuel infrastructure and pursuing a carbon-intensive growth model until late in the decade, that will only make the eventual emission reductions harder and lead to a lot of wasted investment.”

One of China’s richest provinces, Zhejiang in the east, has been more transparent about its energy plans. It has said it aims to increase the share of its electricity generated from clean energy from 37 per cent in 2020 to 57 per cent in 2025, by accelerating development of renewables, nuclear power, distributed natural gas generation, pumped-storage hydropower, and offshore wind, energy storage and hydrogen.

Its provincial five-year plan, published on the Zhejiang government’s website this month, pledged to complete by 2025 construction of at least five offshore wind farms and the first phase of a nuclear power plant as well as planning to expand two nuclear plants to boost installed nuclear power capacity by 22 per cent. Zhejiang also aims to double its installed capacity of solar and wind power.

The neighbouring city of Shanghai has vowed to peak carbon emissions before 2025, five years ahead of the national target, but its decision to limit coal consumption to 43 million tonnes by 2025 and lower coal’s share of the energy mix to 30 per cent have been viewed by some as modest.

03:05

China vows carbon neutrality by 2060 during one-day UN biodiversity summit

Shanghai’s coal consumption had already fallen to 43 million tonnes in 2019, from 47 million tonnes in 2015, and coal’s share of the energy mix last year stood at 31 per cent.

The municipal government says it will increase the share of natural gas – a greener source of fossil fuel than coal – in its energy mix by four percentage points to 17 per cent.

“If Shanghai aims at peaking carbon emissions by 2025, we think it’s too late because they could make it earlier and set a higher bar,” Li Shuo, senior global policy adviser at Greenpeace East Asia, said.

The southern island province of Hainan has also pledged to peak carbon emissions before 2025, add to its installed renewable energy capacity and increase the share of clean energy in its energy mix to 50 per cent.

However, some of the less developed provinces, including in the coal-rich region, have lagged behind or set vague targets.

Shanxi has said only that it will speed up upgrading of coal, electricity, coking and steel industries and promote “clean and efficient utilisation of coal”.

How climate change will affect Asia

Inner Mongolia has said it will increase the importance of green development in assessing local officials’ performance, and promote energy-saving technologies and green technology innovation. It has not set a cap on coal, but said it would strictly control the pace of coal development and promote “clean coal production and efficient mining”.

Some provinces in north and central China, including Hebei, Hubei, Hunan and Jiangxi, have also failed to offer a clear climate target, despite some of them saying they would promote green energy in key industries.

“We worry that some provinces might add more petrochemical or steel projects in the early 2020s and that will delay their peaking until 2030,” said Yang Fuqiang, a senior adviser in Beijing for US environmental group the Natural Resources Defence Council.

“They will then have to work harder and eventually invest more to reduce emissions later,” he said.

03:31

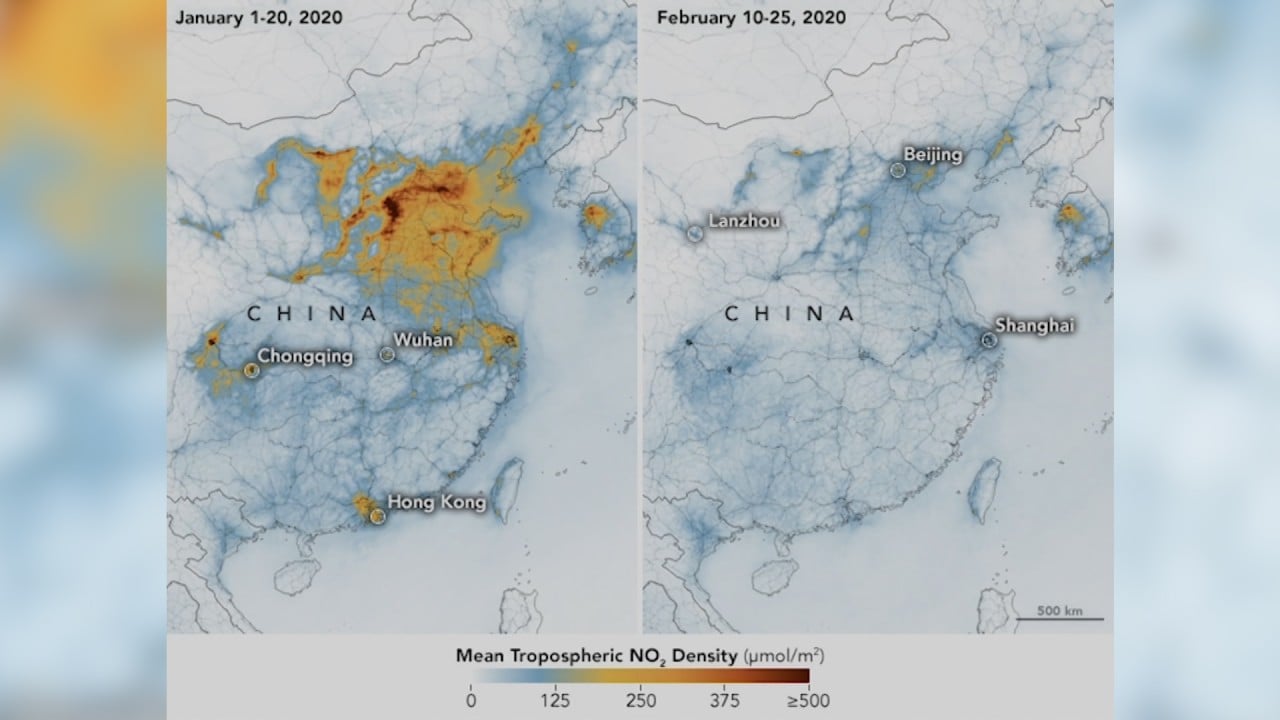

Coronavirus: blue skies over Chinese cities as Covid-19 lockdown temporarily cuts air pollution

“The cap has been set,” Aiqun Yu, China researcher with the San Francisco-based Global Energy Monitor, said. “The carbon debts will roll into the next five-year plan and will accumulate by the year. There is no way to avoid it.

“The low-carbon economic transition will happen a lot sooner than many had thought. The earlier [reforms are introduced], the less pain and more gain economically in the future.”

Myllyvirta said relying less on government spending and more on private consumption and services as drivers of growth would make the low-carbon transition easier.

Yang suggested that the central government could nonetheless balance energy transition requirements with energy demands in the coal-rich provinces.

“Provinces like Shanxi, Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia have been exporting about 70 per cent of the coal they produce, which has increased the difficulty of energy transition,” he said.

“The central government needs comprehensive consideration of the energy transition and the burden of coal and power demands in these places.”