Analysis | ‘Two sessions’ 2021: can China create an ecosystem for tech talent to innovate?

- Beijing seeking to harness China’s finest minds and technological strengths to become a leading innovative country by 2035

- Details in its five-year plan may reveal its intentions regarding research funding and the business environment for tech firms

China’s political elite will gather in Beijing this week for the year’s biggest legislative set piece facing a number of major political challenges, including the aftermath of the coronavirus and the ongoing rivalry with the United States. In this latest article in a series looking at the key items on the agenda, we examine the country’s technology and innovation goals.

“[It] offers a strong platform for multidisciplinary collaborations,” Lee said. “For example, social scientists and neuropsychologists observe behaviour and brain functioning, while neurobiomedical scientists look into the molecular and cellular underpinning.”

Lee’s institute is part of China’s network of more than 500 “state key laboratories”, which serve as the cradle of its basic scientific research specialists.

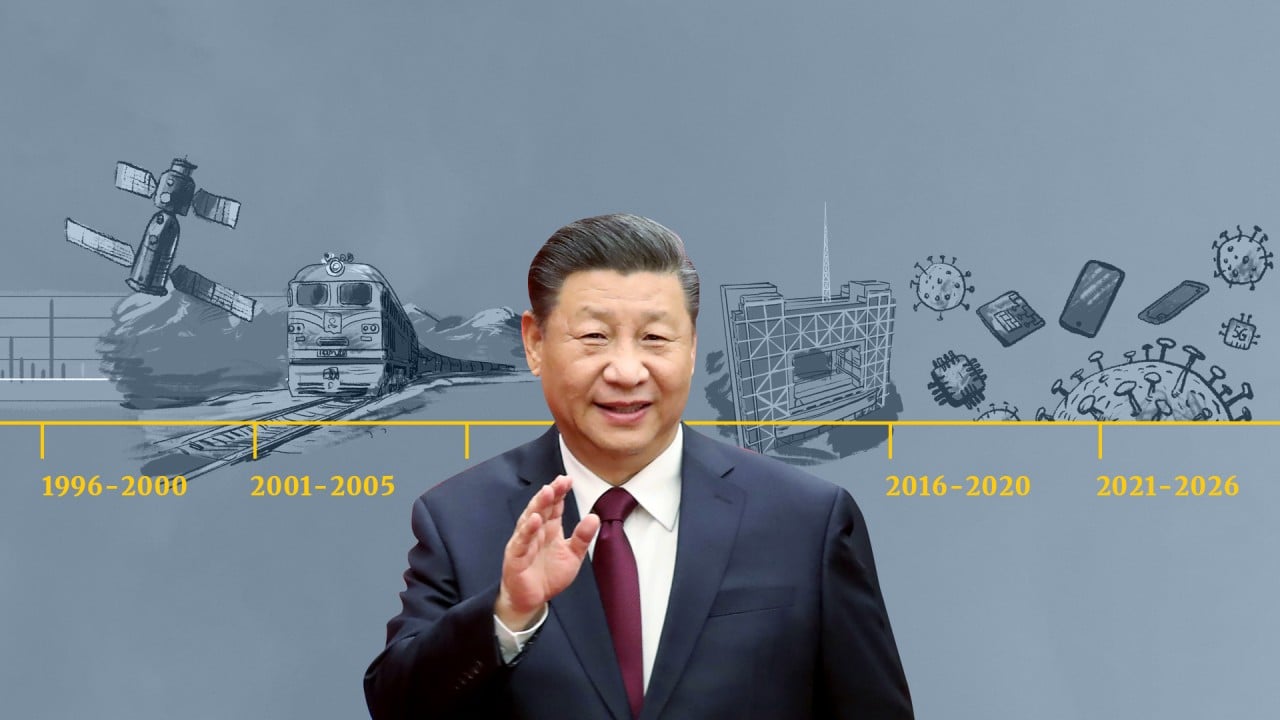

As the annual session of China’s National People’s Congress begins this week, observers are looking for signs of Beijing marshalling its technological resources and policies to pursue its aim of becoming a leading innovative country by 2035.

03:42

SCMP Explains: The ‘two sessions’ – China’s most important political meetings of the year

China’s hi-tech direction for the next five years

Margaret McCuaig-Johnston, a senior fellow at the University of Ottawa’s science, society and policy institute, said the new five-year plan “will need to be more aggressive” if China is to become more competitive in innovation.

MacroPolo, an in-house think tank of the Paulson Institute in the US, has projected that China’s technology ecosystem could reach a level “on par with Silicon Valley in terms of dynamism, innovation and competitiveness” by 2025.

But Cao Cong, a professor of innovation studies with Nottingham University Business School China, said that, even if the five-year plan will offer a glimpse of China’s strategies, a longer-term blueprint to be released later this year must also be taken into account.

According to him, proposals from the outline five-year plan – such as “strengthening the national strategic force in science and technology” and building a new tier of top “national labs” – will need to be understood in the context of the country’s medium and long-term science and technology development plan, covering the 15 years to 2035.

One area worthy of attention, Cao said, was that basic and applied research combined accounted for only 17 per cent of China’s R&D spending in 2019. Government-financed R&D accounted for only about 20 per cent, lagging behind other advanced countries at a comparable stage: when their R&D spending reached 2 per cent of GDP, the United States was financing more than 60 per cent and Germany 42 per cent, according to Cao.

“It will become more difficult for China to gain access to foreign science and technology if a global technology decoupling happens, and then it will have to rely on its own scientists – dependent on how much it has invested in research,” he said.

Efforts by former US president Donald Trump and his administration to cut off China’s access to advanced technologies and know-how spurred Beijing to double down on its commitment to indigenous innovation in science and technology.

A briefing for the US Congress in January on China’s new five-year plan said the US may wish to examine China’s access to American open-source technology and basic research, and assess whether export controls should be tightened.

To maintain their edge in some fields and gain ground in others, Chinese researchers need government support, according to Cao.

“Basic and applied research is largely a responsibility of the government, not corporates,” he said.

Matt Sheehan, a fellow at MacroPolo who wrote its technology assessment report, said the outline five-year plan released last November suggested Beijing was leaning more heavily towards research.

China’s five-year plan to focus on independence as US threat grows

“It puts far greater emphasis on patching up this weakness [on research] than on specific goals for market deployment of technologies,” Sheehan said, citing capital-intensive 5G telecoms infrastructure as an example of the latter.

Zheng Shilin, a researcher at Peking University, has written in a recent research note that although China may overtake other countries by 2035 in total research funding, number of researchers and patent applications, it may be difficult to catch the top tier when it comes to research spending as a share of GDP or total R&D spend – or even to reach the US’ 2000 level.

Despite projecting China would be a world leader in industrial technology application by 2025, the MacroPolo report called Beijing a “fragile tech superpower”, saying it remained vulnerable to interruptions to its supply chain for advanced computer chips. US export controls on semiconductors, introduced during the Trump administration, would apply “a modest brake”, it said, to China’s new infrastructures in areas including 5G, artificial intelligence and the internet of things (IoT).

“If the US can coordinate tighter export controls with countries like Japan and the Netherlands, it would make it a lot harder for China to catch up in critical technologies such as semiconductors,” he said.

05:57

SCMP Explains: China’s five-year plans that map out the government priorities for development

“If the new administration turns down the heat on Chinese students and researchers, makes them feel less threatened [in the US], it would also go a long way towards keeping top tech talent here in the US and out of China,” he said.

However, coordinating several countries’ science and technology policies regarding China “will not be a simple matter”, according to John Lee, a senior analyst with Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies.

“The technological progress being made in many areas by Chinese firms means that they now often present serious competition to US, European, Japanese and Korean players,” Lee said. “Yet this progress is also enhancing the attractiveness of Chinese actors as technological partners, while the development of markets and innovative technological ecosystems in China also creates strong incentives for foreign firms to remain engaged in the Chinese economy.”

Cao estimated that foreign firms operating in China have been contributing 15 to 20 per cent of the country’s R&D spending. Some Chinese industries, such as in advanced manufacturing, continue to rely on foreign equipment – numerical control machine tools from Germany and Japan being one example.

US-China tech war: voices backing US support for chipmaking grow louder

For domestic and foreign firms alike, building and regulating a fairer, more open legal environment is also conducive to innovation.

The outline five-year plan includes policy directions to improve enforcement of intellectual property rights protection and strengthen anti-competition investigations. A more level playing field would be vital for shielding science and technology start-ups from tech giants, Cao said.

The MacroPolo assessment predicted that start-ups would “take the lead” in the next phase of China’s digital economy, with new growth coming from industrial internet applications such as IoT, after the past decade brought a rise of internet giants providing consumer-focused online services.

“The legal environment is the most important ‘software’ powering the innovation ecosystem,” Cao said. “If [China can] get it right in the next five to 15 years, that would greatly accelerate its quest to be an innovative country.”

China has had anti-monopoly laws for more than a decade, but until recent months, the cases brought in the technology sector involved mostly foreign firms such as Microsoft, Broadcom and Nokia, and seldom domestic tech firms.

03:29

US and EU must prepare for ‘long-term strategic competition with China’, says Biden

That tide has been turning, with government regulators taking on domestic tech giants in anti-competition probes and introducing new competition rules.

Analysts said Beijing was unlikely to fundamentally change policy towards tech firms or alter China’s tech trajectory, if it refrains from direct control over tech companies’ daily business decisions.

Lee said recent regulatory moves had shown an intention to allow big internet businesses to keep flourishing, within defined boundaries.

“The Chinese authorities still want to reap the benefits from the development of the internet-based economy and the technical capabilities of China’s technologically innovative firms,” he said.

Wang Zhigang, the science and technology minister, reaffirmed last Friday at a press conference in Beijing that China would push for a model that would place enterprises as the leading driving force for innovation.

“Our innovation ecosystem is not effective enough,” Wang said.

“Building a complete system involving universities, research institutes and businesses, and tackling the shortage of top talent and research teams … will require us to continue our efforts to improve and upgrade.”