Explainer | Tiananmen Square crackdown: what the ‘June Fourth incident’ in 1989 was about

- The reported death toll varies, from the Chinese State Council’s official count of around 300 to a student union estimate of 4,000

- Today, after the global backlash has faded, there are few signs of the tragedy in Beijing and most people in China have learned to forget

Here’s what you need to know about the Tiananmen Square crackdown, which is sometimes also referred to as the “June Fourth incident”.

What were the protests about?

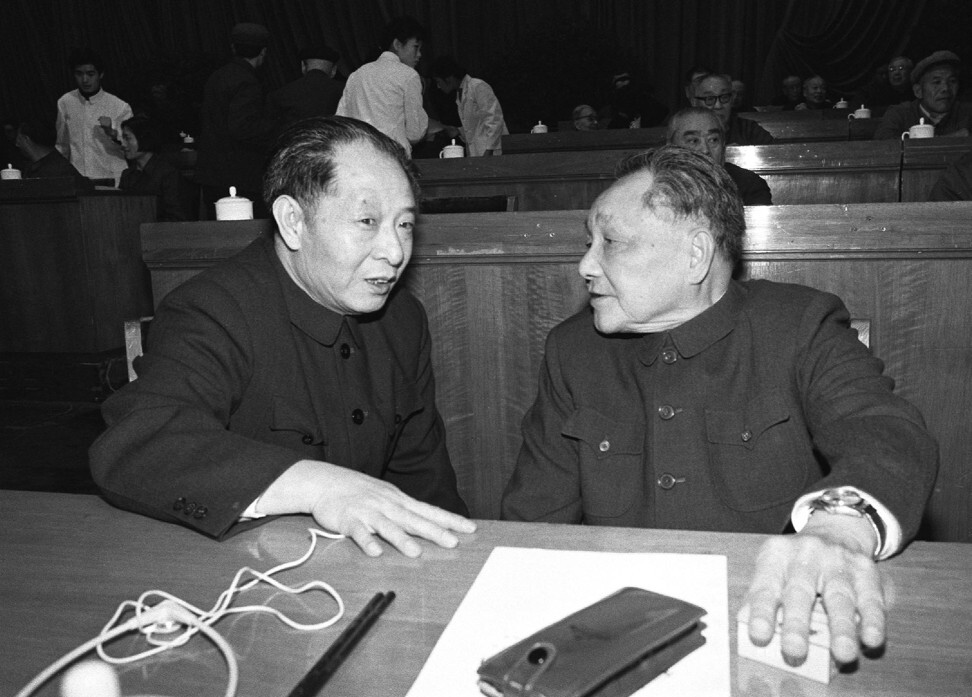

The party at this point was in a constantly shifting balance of power between the liberal camp – more tolerant of relaxing political and economic control – and the conservative camp that was highly suspicious of those experiments.

Despite enjoying popularity among the people, Hu lost the trust of party elders after sympathising with student movements that called for political liberation.

What is the most powerful position in China’s Communist Party?

Public anger about inflation and corruption gained traction in the 1980s under Zhao’s “dual-track system”, which was expected to serve as a transition to the further “marketisation” of China’s economy.

The system involved two sets of pricing systems – goods below a state-set quota were sold at the existing, subsidised prices under China’s planned economy, while goods produced above the quota could be sold at market-determined prices.

This generated huge wealth for those who were able to obtain products at state-subsidised prices and sell them at higher market prices. Unfortunately, many of those who benefited most were those who enjoyed proximity to power: the sons and daughters of party leaders.

Guandao, or official profiteering, became a common target across the political spectrum, and social discontent over the rising inflation rate and corruption after a decade of political liberalisation and economic privatisation reached a peak in 1989.

Against this backdrop, Hu’s death in April 1989 became a political flashpoint and about 100,000 protesters – mostly students but also intellectuals, musicians, artists, workers, small business owners and even some government officials – marched on Tiananmen Square, one of Beijing’s most iconic landmarks, in a display of anger, sadness and sympathy for the former party leader.

They put up large portraits of Hu surrounded by wreaths and banners, and called for a more transparent system and an end to corruption – two causes he had championed.

At a time when the party’s control over the media was at its lowest level in decades, news about the protests travelled fast in the country, creating a snowball of domestic support. Demonstrations broke out across the country over the next few weeks.

In May, some students started a hunger strike and sit-in at Tiananmen Square less than two weeks before then-president of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev was expected in Beijing.

The protesters succeeded in capturing international attention when foreign reporters in Beijing, there to report on Gorbachev’s visit, started covering the students’ hunger strike live.

How did the military get involved?

Party leaders were initially divided over how to respond to the protests. Some, such as Zhao, favoured dialogue with the students, while others pushed for stricter action. Eventually, senior leaders led by Deng decided to impose martial law on May 20, 1989.

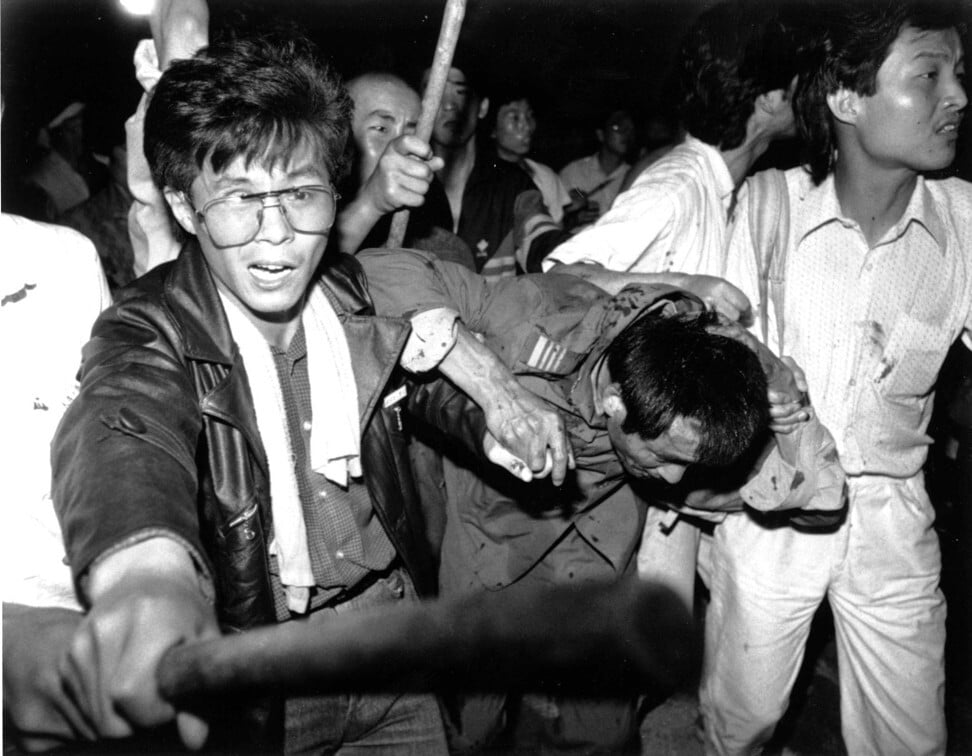

The movement of troops into the city was slowed at first by overwhelming crowds of demonstrators, some of whom lay on the streets to stop the troops from advancing.

But on the night of June 3, the military opened fire.

In a bloody crackdown that lasted well into the next day, troops used tear gas, machine guns and even expanding bullets – a type of bullet that expands inside a victim’s body to inflict as much damage as possible – against the demonstrators.

The reported death toll varies, from the Chinese State Council’s official count of around 300 to that of the Beijing Independent Student Union – one of the first groups involved in the protests – at 4,000.

What happened in the aftermath of the crackdown?

The backlash from the international community was swift. Sweden and the Netherlands froze diplomatic relations with China, while the United States and a forerunner of the European Union announced a plethora of sanctions. Protests against the Chinese government erupted in the US, Canada, Taiwan and Macau.

In Hong Kong, still a British colony at the time, more than a million people took to the streets in support of the student movement and to protest against the Beijing military’s actions.

After the crackdown, the party moved to sideline key players in its liberal wing. Then-general secretary Zhao, who had been supportive of free-market reforms and sympathetic to the student protesters, was purged politically and placed under house arrest for the rest of his life.

A nationwide manhunt also ensued, after then-premier Li Peng called for those who supported or took part in the demonstrations to be imprisoned.

How is the crackdown remembered in Hong Kong and Beijing?

Over time, the Chinese government has largely swept the tragedy under the carpet. The effects of the global backlash have faded over the years, with only the EU’s arms embargo and sporadic statements by Western leaders on the June 4 anniversary remaining as reminders.

In Hong Kong, which was returned to China in 1997, a candlelight vigil for the victims has been held every year on June 4 since 1990 in Victoria Park.

Today in Beijing, there remains little sign of the tragedy. With the media and internet inside China under tight government control, most of the public have learned to forget about the episode.

But almost every year, a brief and little-noticed announcement is made, a day or two before the anniversary, about the temporary closure of some exits of the subway station at Muxidi, some 5km (3 miles) west of Tiananmen Square.

It was in that area that the military fired shots at students who had set up barricades, killing dozens of protesters and bystanders in one of the bloodiest scenes of the crackdown.