Chinese researchers say Xinjiang forced labour claims can’t be true because of increased mechanisation and earning potential from picking cotton

- The global fashion industry is wrestling with the question whether to use Xinjiang cotton over human rights concerns

- The study says ‘Western accusations have no factual basis’ and says Uygurs are being lured into the fields by financial incentives

China sanctions Belgian lawmaker for motion warning of genocide risk against Xinjiang Uygurs

The Better Cotton Initiative, the world’s largest cotton sustainability programme, said it had ceased all field-level activities in Xinjiang in October due to human rights concerns and suspended all licensing for the region in March.

However, the statement was removed from its website when foreign clothing retailers, many of them BCI members such as H&M and Nike, faced calls for a boycott in mainland China for avoiding cotton produced in Xinjiang.

China produces 22 per cent of the world’s cotton, 84 per cent of which comes from Xinjiang, according to a report by the US-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

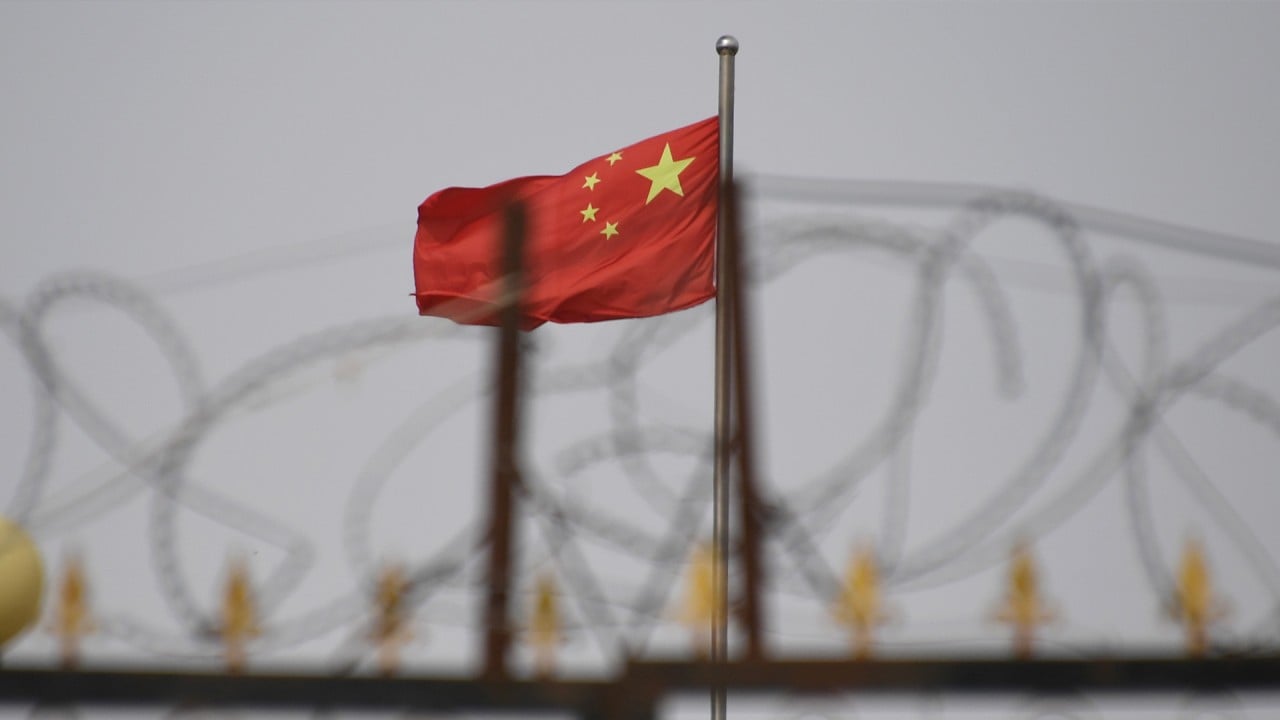

The new research paper provides a rare glimpse into current trends in mainland Chinese scholarship on Xinjiang, which has been subject to strict censorship since 2017, when a mass crackdown designed to “eradicate terrorism” started targeting Uygurs.

Dozens of Uygur scholars have been detained in re-education camps or handed long prison sentences, according to the Xinjiang Victims Database.

Meanwhile, Han Chinese scholars in Xinjiang and other provinces have recently produced a stream of papers to challenge the Western narrative about human rights abuses.

Zenz’s paper cited a news report from China’s Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs that said cotton-picking in southern Xinjiang had only been 20 per cent mechanised by the end of 2018.

What is going on in Xinjiang and who are the Uygur Muslims?

He argued that the need for manual labour was being used as a policy tool to subject Uygurs to “coercive labour conditions involving ‘military-style management’ and political indoctrination, such as singing ‘red songs’”.

But the Chinese research paper said that interviews conducted in the southern prefectures of Hotan, Kashgar, and Aksu showed mechanisation was rapidly increasing in the cotton industry.

It said mechanised cotton-picking accounted for over 70 per cent of all cotton sown in Xinjiang, although they did not give a source for their claim.

But they did cite a list published by Xinjiang’s agriculture department that showed the local authorities were subsidising the mechanisation process.

The paper also cited interviews in several counties of southern Xinjiang to show that mechanisation levels were over 50 per cent, and in some cases drones and other advanced technologies were being used.

“In today’s southern Xinjiang, through measures such as high-standard farmland construction, land transfer and national agricultural machinery subsidies, cotton production has achieved large-scale mechanisation, and the demand for labour has been greatly reduced compared with the past,” the paper said.

In December, an analysis of Chinese government documents by the Washington-based Centre for Global Policy found that in 2018 “at least 570,000” people had been forcibly mobilised to pick cotton there.

UK ‘Uygur Tribunal’ begins as China and West clash over Xinjiang genocide allegations

An earlier report from 2019 by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies think tank said members of ethnic minorities from Xinjiang were being coerced to work in local factories under a poverty-alleviation scheme, sometimes at less than minimum wage, where they were also taught Mandarin and subjected to strict surveillance.

The Chinese research paper did not address claims that labour transfers or poverty-alleviation schemes were being used as a means of repression, but it emphasised that financial incentives, not coercion, were why Uygurs in the underdeveloped southern part of Xinjiang chose to pick cotton.

The paper took pictures showing the amounts of cotton picked by some of the Uygur farmers, from there calculating that they could earn upwards of 20,000 yuan (US$3,125) in 50 days of harvesting.

These earnings surpass the average disposable income of Xinjiang’s rural residents of 13,122 yuan, said the paper, citing local government statistics.

Xinjiang government criticises US, says forced labour claim is ‘card played by anti-China forces’

“From the current point of view, compared with other occupations, the high income from cotton picking makes it an extremely attractive position for the people of southern Xinjiang,” said the paper.

No authors were listed on the paper but a footnote gave the email address of Shang Haiming, associate professor at the Southwest University of Political Science and Law’s Centre for Human Rights.

Shang did not respond to an emailed request for comment.