Chinese academic under fire over ‘historical nihilism’ remarks

- Ge Jianxiong apparently defended the Communist Party’s tight grip on narratives, setting off a rare public discussion

- One historian says it was ‘shameless’ for him to change his stand, but Ge says he pointed out an inconvenient truth

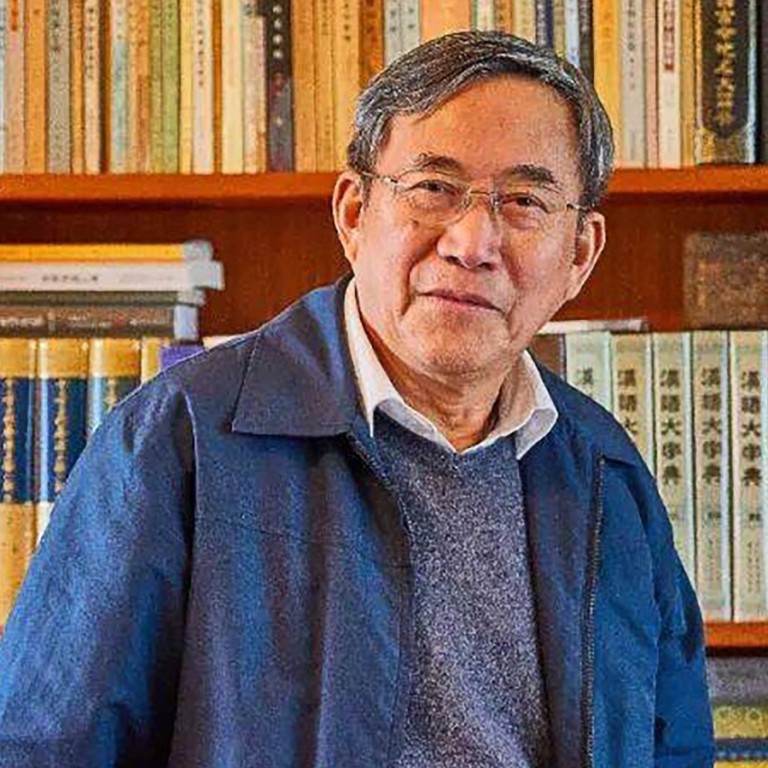

Photos showing key points from a January speech by Shanghai-based historian Ge Jianxiong were circulated on Chinese social media last week, setting off a rare public discussion about the party’s grip on the study of history.

In his speech at Xian Jiaotong University, Ge argued that China’s official version of history had been used as a tool to maintain rulers’ legitimacy for thousands of years, and that the same was true now.

“Oppose historical nihilism, ensure the legitimacy of the Communist Party of China,” read one slide in his presentation, seen in a photo showing Ge at a lectern that has been widely shared on social media.

“Historical nihilism” is a term coined by Beijing that refers to discussion or research that challenges the party’s official version of history.

06:45

SCMP Explains: How does the Chinese Communist Party operate?

According to another photo, Ge also repeated a standard line often seen in state media: “history has chosen the Communist Party and the Chinese people have chosen the Communist Party”.

Another slide stated that research should serve the national interest.

Ge has for decades been an outspoken figure who publicly challenged China’s one-child policy and pushed for laws requiring officials to publicly declare their wealth. His speech apparently reflecting Beijing’s official line has come under fire from within Chinese academia.

Yang Zhengguang, a historian in Shenzhen, said in an article posted on WeChat that it was “shameless” for Ge to change his stand and defend the official line. He also slammed Ge for using the line that “history has chosen the Communist Party”, saying the same could be said of Nazi Germany and former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

It comes as Beijing prepares to mark the party’s centenary on July 1, with officials around the country told to redouble efforts to maintain social stability and tighten ideological control.

Ge took to Weibo to defend himself on Thursday last week, saying he had pointed out an inconvenient truth and denying he was pandering to the government.

“I said that [the study of] modern history is not an academic issue but a political [one] meant to validate the legitimacy of the ruling party,” he wrote. “I was trying to tell young people that they should not naively believe that modern history is an academic subject that everyone can freely discuss.”

He also wrote that he had been stating a fact when he said Chinese dynasties had used history to legitimise their rule.

But his response has only fuelled the debate.

“What he said was terrible,” said Xiao Gongqin, a well-known historian in Shanghai. “Not only did he discourage researchers from studying modern history that the party might disagree with, he was also saying that what party leaders do now is no different from all previous rulers,” he said.

“Any attempt to add to one’s legitimacy to rule by not allowing others to express [opinions] is a delusion from the feudal era.”