China’s Communist Party turns 100: how each generation justifies its rule

- Every generation of leadership must define what constitutes ‘good governance’ – whether it’s economic or geopolitical victories or beating Covid-19

- Except for the reunification of Taiwan, Xi Jinping has offered few clues to what ‘rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation’ means for his leadership

As China marks a century since the founding of the Communist Party, this series looks at the past, present and future of the country’s political system. Here, Jun Mai looks at the foundations on which each generation of the party leadership has sought to build its legitimacy.

One can take the kingdom by force but should never govern it by force, Emperor Gaozu of Han was told by his aide Lu Jia some 2,200 years ago.

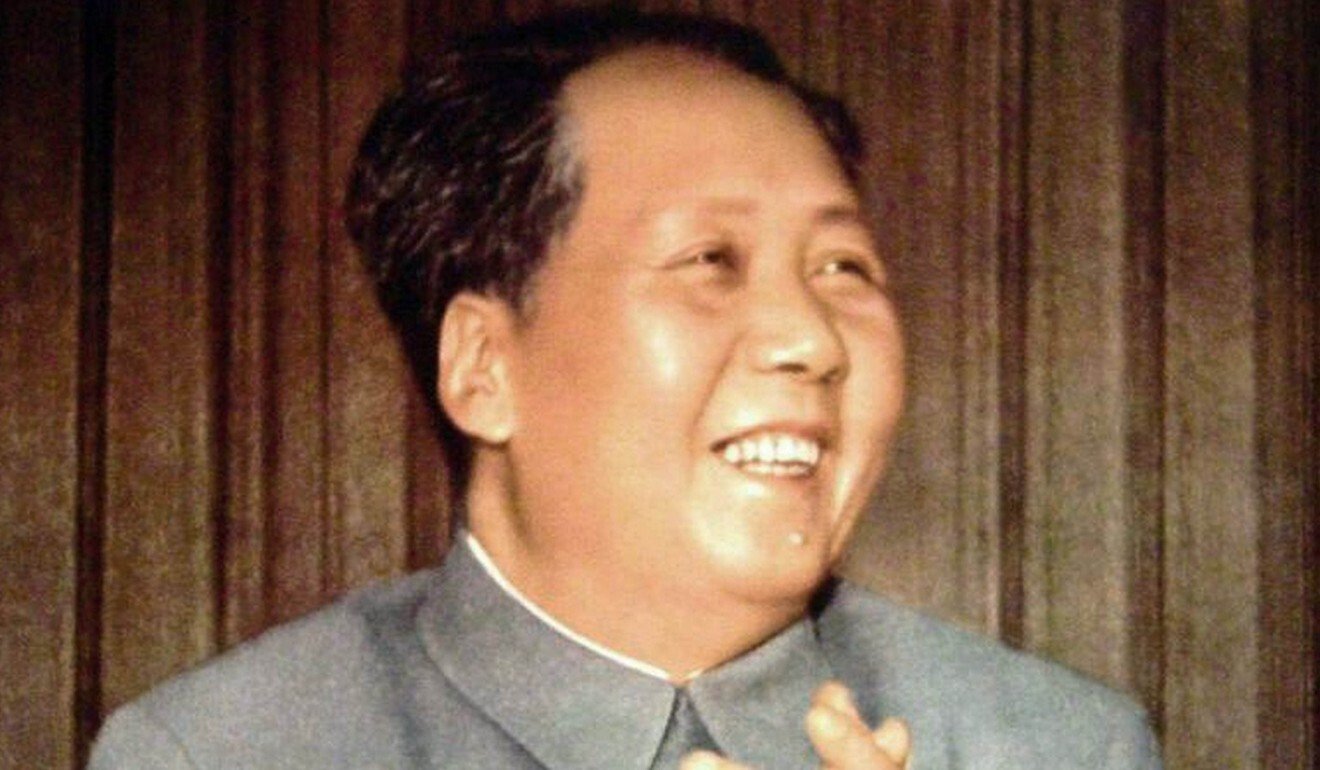

Gaozu of Han, a commoner upstart who eventually built the first centralised dynasty of China, is often compared with Mao Zedong. The great helmsman himself was well versed in the success story of Han Gaozu and liked to lecture it to others.

Mao famously said that political power grew out of the barrel of a gun. But like the Han emperor, he also understood the best way of hanging on to it was by gaining popular support. The use of force should only be kept as the last resort.

Under the one-party dictatorship, Chinese people are not given the chance to vote for an alternative government. But the party, still priding itself that it “serves the people”, has tried to deliver its mandate by other means.

Every generation of the party’s leadership must define what constitutes “good governance” and come up with a matrix to measure it.

Mao, whose portrait still hangs in Tiananmen Square, built his mandate as a founding father of a truly independent China that aspired to represent the lower class and thus the absolute majority of Chinese in the late 1940s. Beijing became a nuclear power under Mao, as well as the sole representative of China in the United Nations.

Deng Xiaoping put an end to the endless ideological struggle that came under Mao, resulting in one of the most spectacular wealth creation stories in history.

These mandates, coupled with a merciless control of political expression, have helped the party‘s rulers survive major crises such as the Cultural Revolution, a decade of nationwide turmoil ordered by Mao in 1966, and the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown ordered by Deng.

The party has prided itself on defying the predictions of naysayers. It has managed to hold on to power and thrive despite disasters, internal strife, incessant power struggles, the allure of foreign culture and lifestyle and pressure from Western countries.

Quite the opposite, the party has publicly laid down ever more ambitious goals that would have seemed distant just years ago, such as being self-reliant on high technology, fighting income inequality and reunification with Taiwan, which Beijing considers a breakaway province.

“China is obviously not another Communist Party of the Soviet Union,” deputy minister of foreign affairs Xie Feng proudly told dozens of diplomats in Beijing, just two weeks before the party’s centenary.

While the sources of the party’s legitimacy have changed over time, they have remained “tangible” for most Chinese, according to Deng Yuwen, a former deputy editor of Study Times , a Communist Party publication.

“The source of legitimacy under Mao was the ongoing revolution, and sometimes Mao himself,” he said. “In the reform and opening-up era [1978 until now], it shifts to economic development and letting the people get rich … there is always something tangible for the Chinese people.”

A survey by the Harvard Kennedy School published in July last year suggested that the party’s legitimacy based on economic development continued to pay off well into Xi’s presidency, concluding that the attitudes of Chinese citizens towards the government appear to respond, both positively and negatively, to real changes in their material well-being.

It concluded that support for the government had grown between 2003 and 2016 but could be undermined by the twin challenges of declining economic growth and a deteriorating natural environment.

On top of economic performance, the party under Xi had also sought legitimacy in areas such as its response to the Covid-19 pandemic and ideological factors, said Rana Mitter, director of the University of Oxford’s China Centre.

“There are several sources of legitimacy. Economic performance and dealing with Covid have been part of the mixture, but ideological factors are also key,” he said.

“Key factors are drawing on modern history, including China’s history as a victim during the opium wars and as a victor during World War II, appealing to aspects of premodern Chinese philosophy and ethics, and a revival of Marxist-Leninist norms.”

As the Communist Party turns 100, Xi has a problem: who will take over?

As public opinion towards China plunged elsewhere, especially in developed countries, after the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, Chinese officials capitalised on Beijing’s swift and forceful response to the crisis.

They played up “the orderly governance of China and the chaos in the West”, as China emerged as the first major economy to achieve positive growth after the coronavirus outbreak.

In June, state-backed propaganda argued loudly that “China has not disappointed socialism”. The party’s ideology gurus have argued since 2017 that Xi’s political thoughts are “Marxism in the 21st century”.

But Deng Yuwen, the former state media editor, said Xi and the party were still undergoing a process to refine a new mix for legitimacy.

“The party feels it needs new sources of legitimacy as economic growth slows down, and they call it the rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation,” Deng said.

The term “rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation” has gone through ups and downs in the party’s propaganda but no past leader has used it as often as Xi. Only months after he assumed the party’s top job in 2012, Xi set a deadline for hitting the finish line of rejuvenation in 2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic of China.

So far, Xi has offered few clues to what that goal means, except for the conquest of Taiwan, more than 70 years after Kuomintang forces retreated to the island during the civil war.

“[Rejuvenation] is not something easy to measure, if we are talking about raising the living standards of the Chinese people, that’s something both Mao and Deng could claim,” he said. “But the reunification of Taiwan is something tangible.”

In an open letter addressed to compatriots in Taiwan in 2019, he referred to the ongoing 70-year-old stand-off between Beijing and Taipei as result of the civil war, as well as “foreign interference”.

“[The party] sees the separation of Taiwan from 1895 to the present day, with the exception of 1945-9, as being the product of imperialist pressures, which is why it associates reunification with the end of its humiliation by other powers,” Mitter said.

“In more recent years, the desire for reunification has been driven by a growing realisation in Beijing that fewer people in Taiwan share their vision of reunification, combined with a growing top-down version of nationalism that is unsympathetic to diverse identities on China’s borders.”

Ties between Beijing and Taipei have plunged to their lowest point in decades. On top of the island’s souring feelings towards Beijing’s authoritarian turn, the tensions were further complicated by US-China rivalry, which saw US allies in the region, such as Japan and South Korea, voicing rare concern over cross-strait peace.

The gesture was met with fury from Beijing, which a week later dispatched 28 fighter jets to the island’s air defence identification zone, in what Taipei called the largest air approach in history.

The unification of Taiwan was especially important not only for the legitimacy of the party but for Xi personally, said Zhang Musheng, a well-connected economist and former official.

“Deng [Xiaoping] put an end to the life tenure of state leaders and pushed for separation of party and state,” Zhang said. “But once Xi is in power, he changed all those and the country is becoming more authoritarian.”

In 2018, China’s legislature passed an amendment to the constitution, lifting the two-term presidential limit that has been in place since 1982.

Who are China’s eight political parties, aside from the Communist Party?

That term limit was imposed amid a consensus among the top party leaders, including Deng, to avoid the recurrence of tragedy under Mao, which they diagnosed as the result of an overconcentration of personal power.

“If he bases his legitimacy on solving the issue of unification, and the concentration of power as a necessary tool for that goal, it’s not a big deal if he stays in power for a few more years,” said Zhang, who is known for his outspokenness and his connection with the party’s ruling elite.

When Zhang, son of a communist revolutionary leader himself, published a book in 2011 on Chinese history, Liu Yuan, then political commissar of the logistic department of People’s Liberation Army, wrote its preamble. Liu’s father, Liu Shaoqi, was president of the People’s Republic and the party’s second most powerful man after Mao before he was purged in the 1960s.

Confident of China’s growing military naval capacity and Washington’s lack of willingness for overseas warfare, Zhang argued that a financial crisis in the United States would provide a good opportunity for Beijing to retake Taiwan.

“If there’s a financial crisis in the United States, then our apologies, we might need to do our stuff,” he said. “The US can’t even deal with Cuba under its nose. Trillions of dollars were spent in Afghanistan and the Taliban is taking over the suburbs and key ports once the US pulls out.”

China ‘unlikely’ to try taking Taiwan in next two years: US general

But Deng Yuwen pointed out that Beijing still needed to weigh the potential risks if it went down the path of taking Taiwan by force.

“Once achieved, it would bring a huge boost to the party’s domestic legitimacy in the short term, something that can be compared with the founding of the People’s Republic of China,” he said.

“But if it takes a war, then it could take resources rebuilding Taiwan,” he said. “The domestic excitement of unification will feel much different after a few years if Western sanctions sink in and affect the daily life of ordinary Chinese.”