Survival of the fittest: sport the new arena for China’s children in tutoring crackdown aftermath

- A government shift towards making physical strength and ability a higher priority is putting pressure on children, parents and newly swamped coaches

- Beijing forecasts the sports sector to be worth 5 trillion yuan by 2025, a 70 per cent increase from 2019 levels

“I’ve cancelled all the off-campus curriculum subject classes for my son and replaced them with sports classes recently,” said Steve’s mother Bai Peipei.

“It’s obvious the Chinese government prioritises the physical ability of children over their academic performance as shown by the recent crackdown [on the after-class tutoring sector],” said Bai, 36, a public school teacher turned housewife in Beijing.

“When the government points in a direction, you have to follow. Otherwise you’ll be left behind in the future cutthroat competition to get into a good university.”

To gain an edge, parents turned to off-campus private tutors, a sector that was booming until July when the central government introduced radical regulations to rein it in, responding to repeated calls by President Xi Jinping to reduce the workload for pupils and the financial burden for their parents.

Under the new rules, the companies are barred from accepting foreign investment and profiting from teaching school curriculum subjects. Teaching subjects such as maths, English and Chinese are prohibited at the weekends, and during public holidays and school holidays.

However, the rules do not apply to those teaching sports and arts, with Beijing picturing a thriving, prosperous and powerful China of people with a “lifelong habit of exercise” and “noble sentiments”.

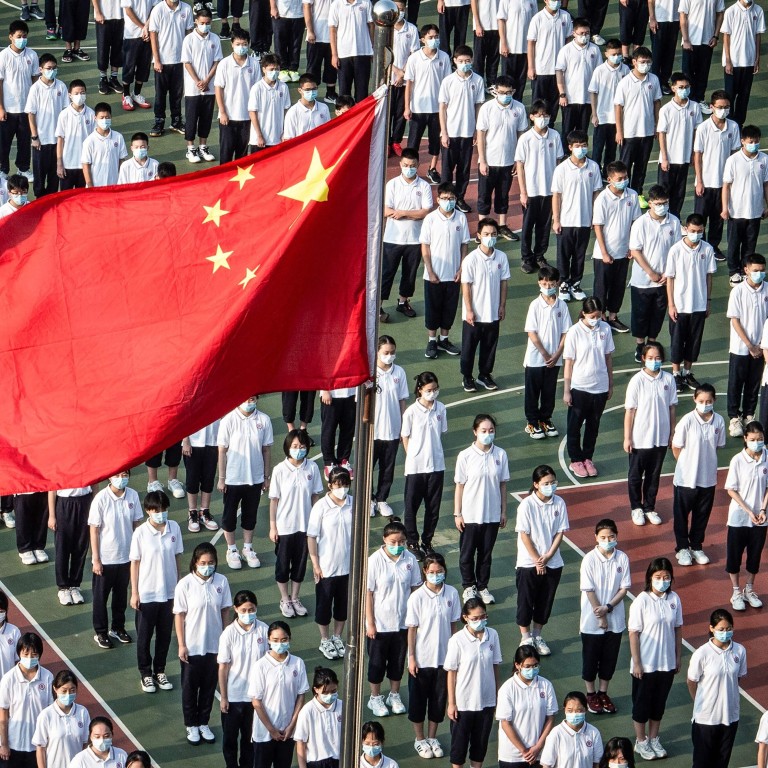

The policy is ushering in new clients for China’s sports industry as parents shift the competition arena for their children to embrace the benefit of exercising – while creating a new source of stress for parents keen for their offspring to succeed and for children striving to meet different expectations.

Eager to distance itself from the humiliating sobriquet “Sick Man of Asia”, the People’s Republic has attached high importance to physical education and athletic performance since it was founded in 1949. After the 2008 Beijing Olympics, China launched a national fitness campaign to encourage people to work out regularly and turn the country into a leading sports power.

What’s the end game for China’s crackdown on private tutoring?

In 2019, China laid out ambitious goals in the Health China Action Plan: for half of all students to score “excellent” or “good” in the annual national physical tests by 2022 and 60 per cent by 2030. It would be a substantial improvement from the 30.3 per cent who met the mark in 2018, according to data provided by the Ministry of Education.

Parents are adapting to the change quickly. Xu Shumei, the mother of a five-year-old girl, said she signed her child up for a rope-skipping class two weeks ago in Beijing at a price of 2,000 yuan (US$309) for 10 40-minute sessions.

“Although Beijing has not changed PE’s weighting in the zhongkao, many people have sensed the trend of the government’s increasing focus on sport,” Xu said.

“Everyone around me is having their children learn rope-skipping. It’s an annual test item in primary schools and middle schools. If you cannot grasp the skill well, you’ll lose your competitive edge.”

Parents in China are giving their children growth hormones to make them taller

China’s physical tests include one minute of skipping, a 50-metre run, a sit-and-reach test, sit-ups, long jump and either a 800-metre or 1,000-metre run. In addition, the students are assessed for their vital capacity and body mass index (BMI) – a measure of body fat based on height and weight – as a measure of their fitness. Students who fail the PE tests are disqualified for the annual honourable title of merit student of the school. Merit students usually have better access to top middle schools.

However, using a skipping rope is not easy for many children. Amy, Xu’s daughter, is “weak and clumsy”, according to her mother. “After making strenuous efforts, she only managed to have a dozen or so passes [over the rope]. So I decided to send her to a training centre to get help from professionals,” Xu said.

China is well positioned to grow its sports industry. Last month, Beijing launched the 2021-25 outline of the nationwide bodybuilding plan, vowing to provide more and better sports facilities and increase the numbers of fitness trainers and people exercising regularly. The government forecasts the sports sector to be worth 5 trillion yuan by 2025, a 70 per cent increase from 2019 levels.

Ma Hui, a badminton trainer and co-owner of a Beijing sports club, said he was made to teach rope skipping this summer to meet skyrocketing demand.

“Our phones kept ringing. We received so many calls from parents inquiring about the training,” Ma said. “Even after we increased the number of trainers from 20 to 30, we still cannot catch up with the demand.”

While parents are more willing to spend on sports training after the clampdown on tutoring classes, they are demanding that their children attain high goals.

“Many clients set quantitative goals – such as one-minute 100 passes in 10 days, or 200 passes in 15 days – as they want their children to score ‘excellent’ in the PE test at school. I’ve been driven crazy!”

Shanghai bans primary English exams, but ‘no one dares to ignore this subject’

Bai, Steve’s mother, said she wanted her son to excel at physical education. “In China, competition is so intense that if you lose one point [in a university entrance exam], you will be behind 1,000 people,” she said.

“While the competition in curriculum subjects may be suffocated by government orders to some extent, parents will be keener for their children to gain some edge in other field, such as sports,” she said. “Anxiety never ends.”