China’s disciplinary enforcers shift focus from corruption to poor performance

- Targeting officials who do not fulfil their duties is an increasingly important task for the Communist Party’s top watchdog, according to a new study

- Anti-corruption drive is still a key part of its role, but the focus has shifted towards low-level ‘flies’ rather than the high-ranking ‘tigers’

It said the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) had shifted from being a “fear-inducing machine” primarily focused on corruption to becoming a “behaviour modification machine”.

The report, by MacroPolo, an in-house think tank at the Paulson Institute, also predicted it would be used to “decouple” the relationship between politics and business in the third phase of its operations.

The Chicago-based think tank said the fear factor was “effective but unsustainable”, because it meant too many officials were frightened to show any initiative in case they are punished for making mistakes.

Beijing’s top leadership is aware of the problem. On Saturday at the opening of the National People’s Congress annual meeting, Premier Li Keqiang hit out at officials who neglect their duties and are “out of touch with reality and go against the will of the masses”, warning them they must “live up to the expectations of the people”.

The report said the commission’s figures showed that between 2019 and 2021 performance-related cases made up more than half – 54 per cent – of the cases it tackled, compared with 46 per cent for financial corruption – a sign the ruling party is “attempting to modify cadre behaviour to ensure that they perform”.

It continued that the CCDI’s National Supervisory Commission “is more institutionalised within the CCDI [and is] attempting to modify cadre behaviour to ensure that they perform. To do so in the Chinese system means focusing on cadre performance evaluations, or key performance indicators (KPIs) in consultant speak”.

In the past six months, the CCDI has issued two instructions stressing the importance of tackling bureaucratic inefficiency. It began incorporating data on performance-related cases in December 2019 and since then has publicised cases where officials were punished for failings such as not implementing directives, losing touch with the people and even holding too many meetings.

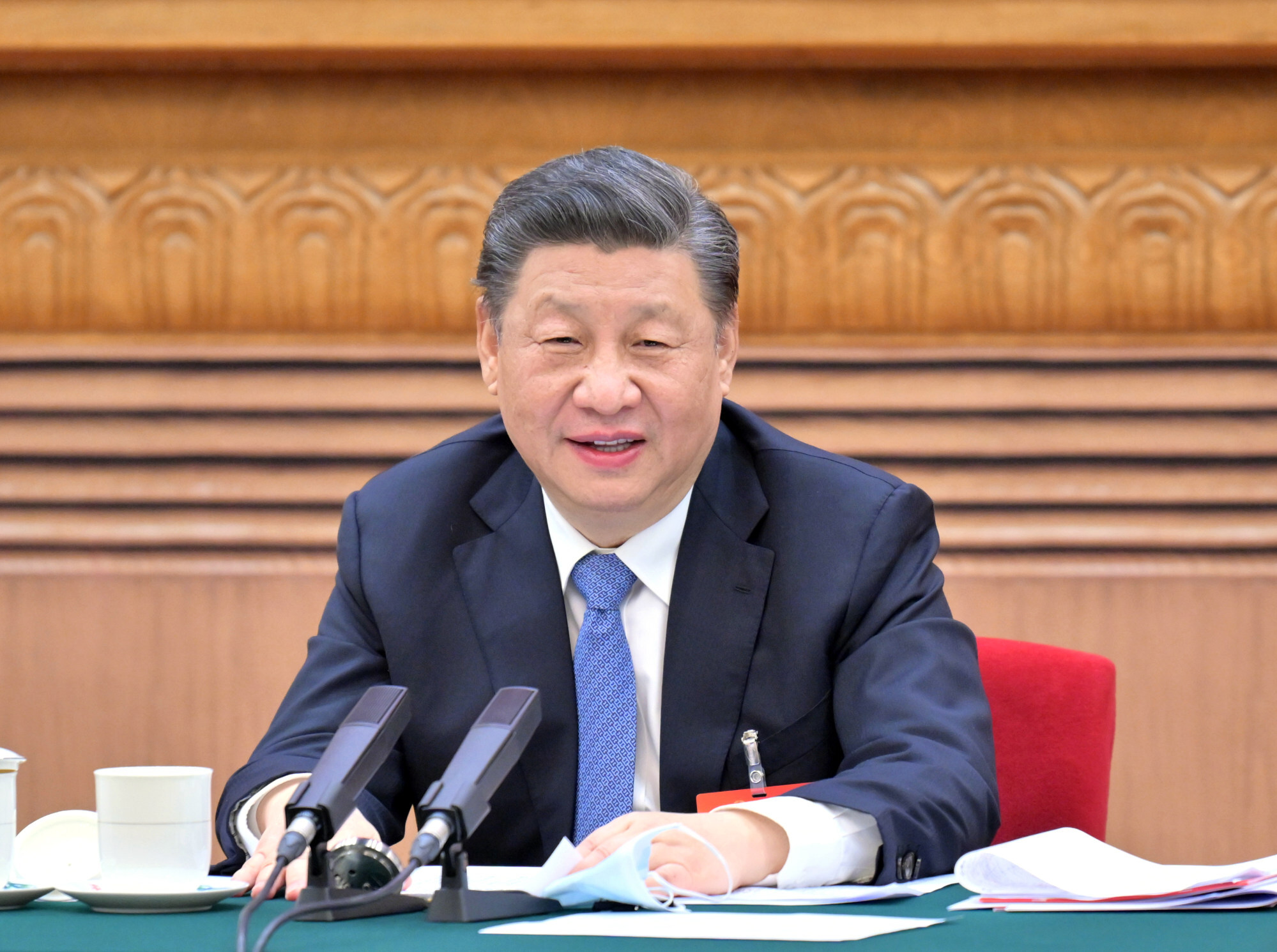

Xi Jinping asks: why do Chinese officials wait for orders from the top?

The report also said the targets of the corruption campaign have shifted from “tigers”, or senior officials, to lower ranking “flies”.

Between 2017 and 2021, the number of county-level cases targeted has risen by nearly 20 per cent, from 523,000 to 624,000.

In the same period only 84 senior officials, just three of whom were members of the policymaking Central Committee, have been jailed for corruption.

By contrast, 145 “tigers” were jailed between 2012 and 2017, including 42 Central Committee members.

“It’s no coincidence that since 2018, Xi has urged the CCDI to shift its focus down to the local level because he considers grass-roots corruption a threat to ‘social stability and the party’s legitimacy’,” the report said.

It also said the CCDI’s next phase appears to be focusing on the “decoupling” of government and business by targeting collusion between officials and business leaders.

The report cited a recent CCDI gathering, where the watchdog aligned itself to recent antitrust and tech crackdowns.

The CCDI recently accused China’s financial regulators of having a “revolving door” arrangement with business.

It also said it would pass on details of the case of former Hangzhou party secretary Zhou Jiangyong, whom it accused of profiting from supporting the “disorderly expansion of local private capital”, to prosecutors and extend the investigation to his family members.

Chinese province sees third police chief in a row accused of corruption

“The empowering of the CCDI in this regard appears to be part of a larger strategy to use both carrots and sticks to shift the private sector’s focus from leveraging political connections to gain competitive advantages to investing resources into creating better products and market strategies,” the report said.

Anti-corruption campaigns have taken down hundreds of “tigers” and the reshuffles that followed allowed Xi to “more or less” fix the national and provincial-level leaderships, said Xie Maosong, a senior researcher with Tsinghua University’s National Strategy Institute.

Xie said it was “natural progress” to move on to the grass-roots level, adding: “No matter which country, the crux of politics is always to win over the people. Among the ordinary Chinese people, national leaders are just too remote.

“To them, grass-roots officials are the face of the party and government. Corruption at grass-roots level, which may be smaller in scale, can inflict direct harm to people’s lives and create injustice. That can cause public anger and damage stability.”

“The lack of transparency within the CCDI’s decision-making will heighten the risk of politically charged investigations, particularly for Chinese businesses with ties to certain CCP factions. Any public announcements of active investigations will likely have a knock-on impact for Chinese stocks as well,” he said.

Breen also said the watchdog had been given a new role controlling local government debts, adding that Beijing is increasingly concerned about local authorities making unwise investments following Evergrande’s default.

He said the focus on financial discipline should be about improving the transparency of debts issued through local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), adding that corruption was not usually the main factor in play.

Former Chinese anti-graft inspector gets suspended death sentence for corruption

“LGFVs enable local authorities to borrow and fundraise through backdoor financing that has circumvented central government regulations,” he said.

“However, it is likely that tackling local government debt will require institutional reforms that could come at a political cost for the Communist Party as it would threaten local initiatives that have been central to China’s economic growth.”