Uneasy times for Hongkongers making their home in mainland China

- Rising Chinese nationalism and distrust after the city’s social unrest have left some Hong Kong people with an identity crisis

- But despite uncertainties over Hong Kong’s future direction, there are opportunities to be found across the border

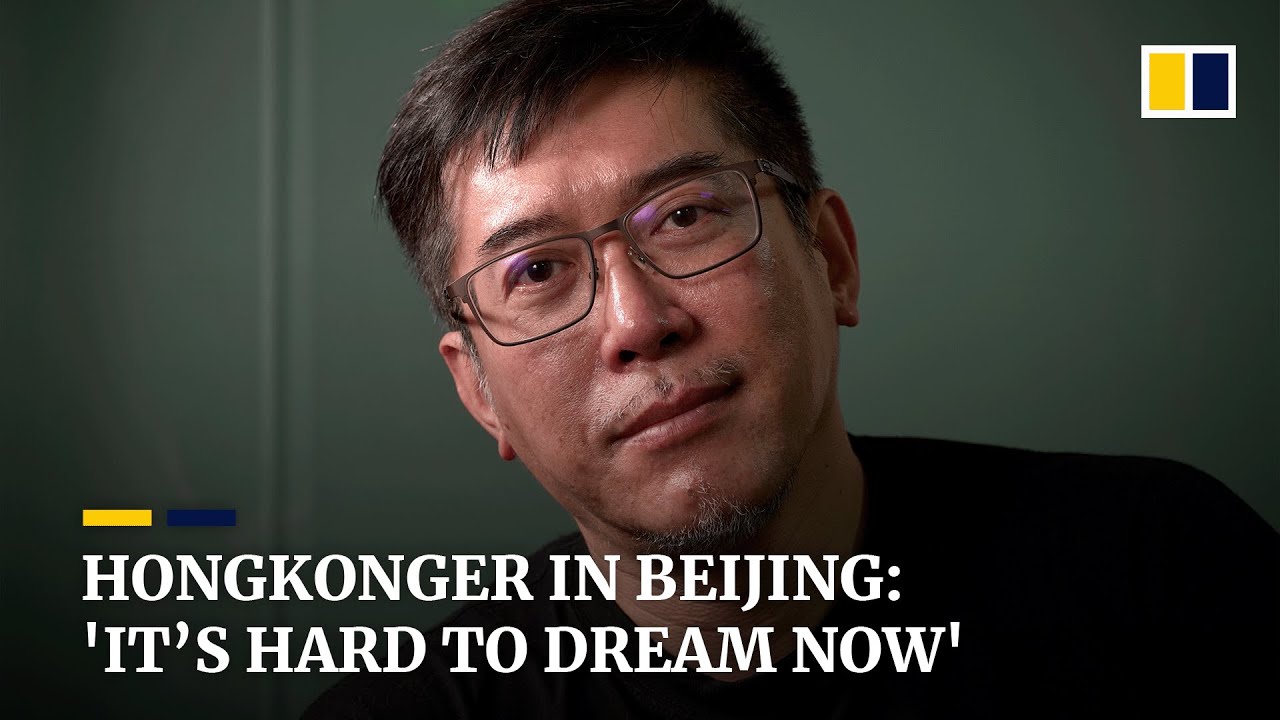

Among them is 56-year-old Bing Chiu, who moved to Shanghai as a creative director in 1998, just a year after Hong Kong’s handover. While his advertising career in Hong Kong had hit a bottleneck, he was soon taking on clients like Motorola and Intel.

World-class production studios were practically non-existent in mainland China, but Chiu pushed through to build a multi-track career as a musician, restaurant owner, radio host and cultural events promoter.

His decision to make his permanent home on the mainland gave Chiu – now a long-term Beijing resident – a front-row seat to China’s miraculous growth, while keeping an eye on Hong Kong from afar. But, after more than two decades of reunification anniversaries, Chiu has never felt more uncertain about the city’s future.

“I held three concerts in the Oriental Plaza [in Beijing] marking the 10th handover anniversary in 2007. It was really an exciting time as we were also anticipating the Beijing Olympics Games in 2008. People were charged with an optimism that a better and brighter future was to come soon,” he said.

“When it came to 2017, I remember feeling lethargic as the relationship between China and Hong Kong had already changed. But there were still great things that we could celebrate.”

But for Chiu, the 25th anniversary feels like just a number. “When the Hong Kong way of life is still being filled with so many unknowns, it begs the question of do we need to celebrate?” he said.

“This is an awkward time for China and Hong Kong. At its 25th juncture, silence seems to run better than thousands of words.”