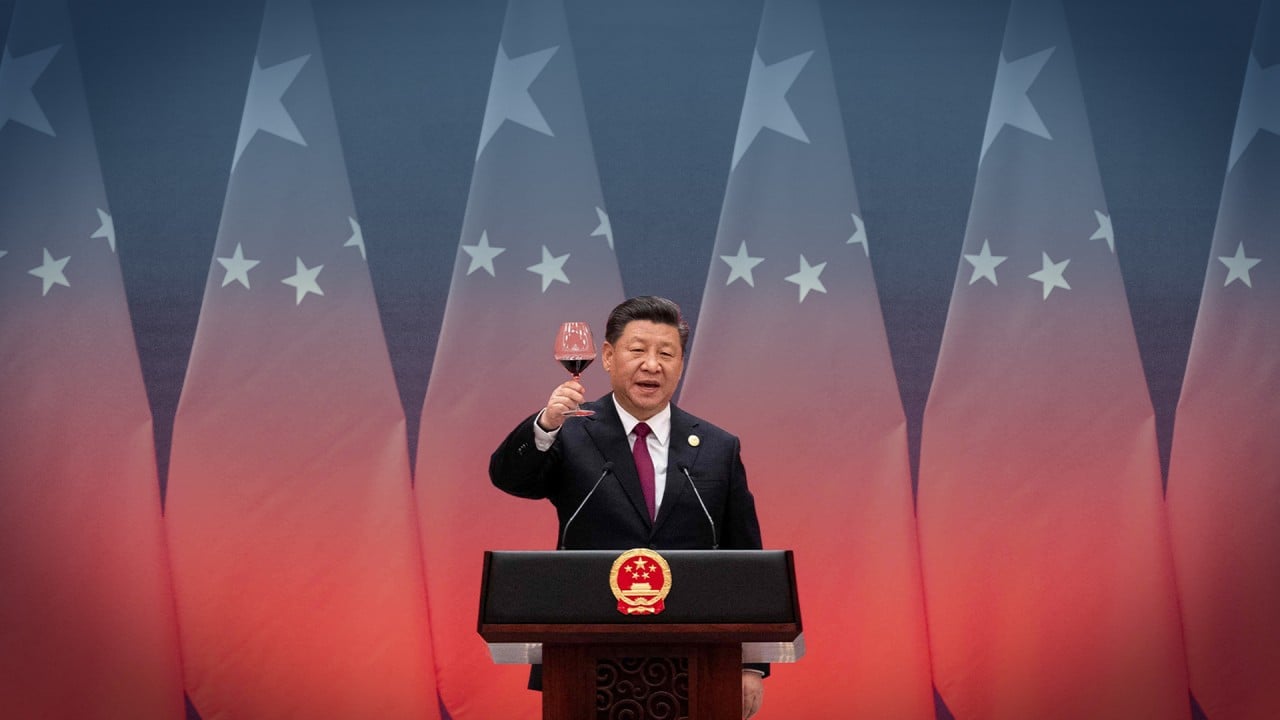

How Xi Jinping’s end to China’s collective leadership model was years in the making

- Political shift made possible by Communist Party consensus to turn away from a system blamed for corruption and discontent, experts said

- The 20th party congress has swept aside mechanisms established after Mao Zedong’s death and concentrated power in Xi

Xi’s changes to the top echelons of the party’s decision-making bodies were bigger than expected, but they also chiselled away at party retirement norms and promotion trajectories, while stepping up the centralisation of power.

In a break with decades of precedent, Xi skipped consultations with party elders over the Politburo line-up, according to state news agency Xinhua. The size of the decision-making body was also cut from 25 to 24, greatly increasing the chance of a tied vote.

Experts believe the tremendous political shift was made possible – at least in large part – because of a consensus to put an end to the fragmentation of authority and intraparty democracy, seen as responsible for decades of corruption, factionalism and associated public discontent.

Xi seized on concerns in the party and the country to present the concentration of power as a solution to the acute political and economic problems faced by China, they said.

“He has made it clear that the compromises that existed in the first 30 or so years of the reform era would no longer apply: factions and divisions in the party would not be tolerated,” said Rana Mitter, professor of the history and politics of modern China at the University of Oxford.

“Xi’s calculation is likely to be that the Chinese economy is large enough that it can cope with a significant period of retrenchment, including relative isolation from global networks, zero-Covid restrictions and, above all, a strong political treatment of sensitive sectors such as technology.

“However, to implement this, it is necessary to sideline leaders who have more traditional views on economics and markets since they would be unlikely to support these policies.”

The new Politburo and its seven-member Standing Committee – where China’s most important decisions are made – were unveiled the day after the party congress ended.

The outcome was a Standing Committee filled with Xi’s core confidants, where candidates considered of a different background – including Premier Li Keqiang and head of political advisory body the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Wang Yang – failed to secure a seat at the Politburo, despite not reaching their unofficial retirement age.

Hu Chunhua – nine years shy of his level’s retirement age and with no proof of wrongdoing – was demoted as well as squeezed out of the Politburo. Hu retains a seat on the 205-strong Central Committee but is set to lose his position as vice-premier because he is no longer high enough in the party ranking for the job.

The trio are all experienced in driving the economy on the national level and lack any obvious connection to Xi’s earlier career.

Retirement awaits China’s Li Keqiang and Wang Yang as Xi builds third term

Two days after the congress closed, a long report by Xinhua said Xi was firmly in charge of the selection process for the party’s new leadership. The number of people he personally consulted on the line-up was down to 30, from 57 five years ago, and did not include party elders, it said.

Zhang Dong, a political scientist with Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said the party under Xi’s leadership had seen its collective leadership mechanism weaken in the past 10 years, along with the power base of his competitors.

“Collective leadership is not an institution but the result of a balance of power or a fragmentation of authority,” he said. “Once the underlying power configuration is no longer balanced, collective leadership will certainly fall apart.”

Zhang said he expected Xi to maintain a balance of power on the State Council – China’s cabinet – which includes long-term allies Li Qiang, from Xi’s Zhejiang days, He Lifeng from Fujian, and Ding Xuexiang, who has risen to power from Shanghai.

“His followers may not agree on every policy issue and might have some internal debates but Xi is likely to be the ultimate arbiter,” Zhang said.

Collective leadership was designed by Deng Xiaoping when he took power as China’s de facto paramount leader after Mao’s death in 1976, to guard against the excesses of a future political strongman causing another turmoil like the Cultural Revolution.

Deng explained his political logic in a 1980 speech on party and state leadership reform in which he criticised “overconcentration of power” for hindering socialist democracy and the party’s democratic centralism.

“It impedes the progress of socialist construction and prevents us from taking full advantage of collective wisdom” and could give rise to “arbitrary rule by individuals at the expense of collective leadership”, he said.

Deng’s solution was to share power among the party elders, in a structure termed “twin peaks politics” by Chinese political scholar Yang Jisheng, with then vice-premier Chen Yun as the other peak. Both camps were in a constant tug of war, but expected to reach consensus on key issues.

While Deng promoted collective leadership, he did not institutionalise the mechanism – which had some flaws, most notably under former president Hu Jintao – within Chinese elite politics, said Xiaoyu Pu, associate professor of political science at the University of Nevada in Reno.

“The collective leadership model has its problems as well, including fragmentation and gridlock, and these became especially salient during the Hu era,” he said.

“Maybe Xi claims that he should concentrate power to overcome the fragmentation problem in the collective leadership model, and that urgent challenges at home and abroad justify the emergence of a more coherent leadership model.”

That rationale was spelled out by Xi last month, in his work report to the party congress. In a long paragraph, he detailed the party’s structural shortcomings inherited in 2012 when he took power.

“Then, years ago, in a series of long-accumulated and new arising conflicts that begged to be resolved, the party saw numerous issues in weakening leadership … formalism, bureaucracy, hedonism, unstoppable extravagance and privileges, and shocking corruption problems,” Xi said.

“At that time, many in the party and in the public sphere were worried and concerned about the future of the party and the country.”

According to Beijing’s narrative, factionalism went so far in the Hu era that there was serious vote rigging during a selection process for the party’s leadership, prompting a change to the system.

Explaining the changes in 2017, Xinhua said the party had learned the lessons of the 17th and 18th party congresses in 2007 and 2012 respectively, which saw hundreds of senior officials casting ballots for leadership candidates at a large meeting, before the results were discussed by the Politburo.

“Some comrades arbitrarily voted or voted based on factions. Zhou Yongkang, Sun Zhengcai and Ling Jihua, which the party central investigated and penalised, vote rigged during conferences,” the article said. All three were former top leaders who were later jailed for corruption.

Three disgraced Chinese officials accused of rigging party votes

The system was abandoned by the 2017 congress in favour of small, face-to-face meetings to determine the leadership. The practice continued this year, when Xi’s power was concentrated to a level unseen since Mao’s death.

In his report to last month’s congress, Xi said Beijing had “fundamentally turned around” the lax management of the party. But his complete victory has many worried, with Pu and other analysts noting the common downside to a concentration of power.

“Some might worry that Xi won’t be able to receive diverse and honest feedback in key decision-making. Any course correction might be even more difficult,” Pu said.

These concerns cast uncertainty on the future for China’s economy – already isolated from global networks and dealing with zero-Covid restrictions, youth unemployment and a fragile property market. Investors responded with a frantic sell-off.

But analysts cautioned against premature judgment. The real test for Xi’s executive team, which took over the State Council in March, is whether it can boost China’s lukewarm growth.

“Xi is undertaking a political experiment that involves a different calculus – that politics can be refashioned to overcome the need either for the divergence of views or conventional views of economics,” Mitter said.

Henry Gao, a professor of Chinese law at Singapore Management University, said he expected Xi to focus more on military and hi-tech development, placing security ahead of economic development.

“However, that unbalanced development with too much focus on the military and hi-tech development will lead to the same problems as the USSR, which ultimately resulted in its collapse,” Gao said.