Why has China’s zero-Covid U-turn sparked so much public resentment?

- Social media posts have complained about a dearth of medications and overwhelmed hospitals

- National Health Commission says fever clinics are open, but admits they are short of medicines

“It was like a nightmare,” Liu Qunzhu said as she recalled accompanying her 75-year-old husband to a hospital in Wuxi, Jiangsu province, two weeks ago.

The hallways were packed with quiet patients and their anxious family members. Liu’s husband, who had surgery to remove lung nodules two months ago, had tested positive for Covid-19 and was feverish for two days, but showed no severe symptoms. Stuck in a long queue at the fever clinic, Liu was about to give up and go home when her husband passed out.

“I was scared to death,” Liu, 68, said in tears. “I yelled for help and knelt down. I begged doctors to admit him to hospital. But they said all the wards were full.”

Such desperation has been shared by hundreds of millions of Chinese people amid the country’s abrupt but seemingly ill-prepared pivot away from its almost three-year-old zero-Covid strategy. Many people have been infected with the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19 in the past few weeks, with some medical experts calling it an “infection tsunami”.

Complaints in social media posts about a dearth of medications, overwhelmed hospitals, ambulance services and funeral parlours, and acute blood shortages are a sign of widespread public resentment.

“It’s ruthless to make us, the vulnerable elderly, pay the price for the government’s haphazardness,” Liu said, adding that all members of her family had received three vaccine jabs and had worn masks when in public spaces.

Cheers, fears and tributes to Wuhan hero Li Wenliang as China marks Covid shift

Her husband was finally given a bed in an intensive care unit after his immediate family, their relatives and friends contacted nearly a dozen hospitals.

“I used to be a faithful follower of all policies of the party,” Liu said. “But this time, I blame whoever is in charge of the policy enforcement. Their irresponsible attitude has thrown us into such deep misery.”

But as disruptions to the economy increased and social discontent with the stringent curbs mounted, sparking widespread protests in November, China announced it would abandon most zero-Covid requirements – from PCR tests to quarantine and health codes – from December 7.

Chinese authorities have not explained why there was no communication with the public before the policy U-turn on whether the two main problems used to justify the zero-Covid strategy – a low vaccination rate among the elderly and a low number of ICU beds – had been resolved.

Unlike many countries, China had focused on vaccinating young and middle-aged members of the workforce, rather than the more vulnerable elderly. According to official figures, only about 40 per cent of people aged 80 and over on the Chinese mainland had received a booster dose by the time the country began to reopen last month.

And the commission said on December 9 that the number of ICU beds on the mainland stood at just 138,100, close to 10 beds for every 100,000 people. That compares to 34.7 beds per 100,000 in the US and 29.2 in Germany.

China shifts Covid focus to critical care with push for more beds

“Apparently they don’t have an exit strategy,” said Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank based in the US.

“A smooth exit should be gradual, lifting curbs step by step and communicating clearly with the public beforehand. As a result, it would not have caught medical workers off guard and terribly overwhelmed the medical system.”

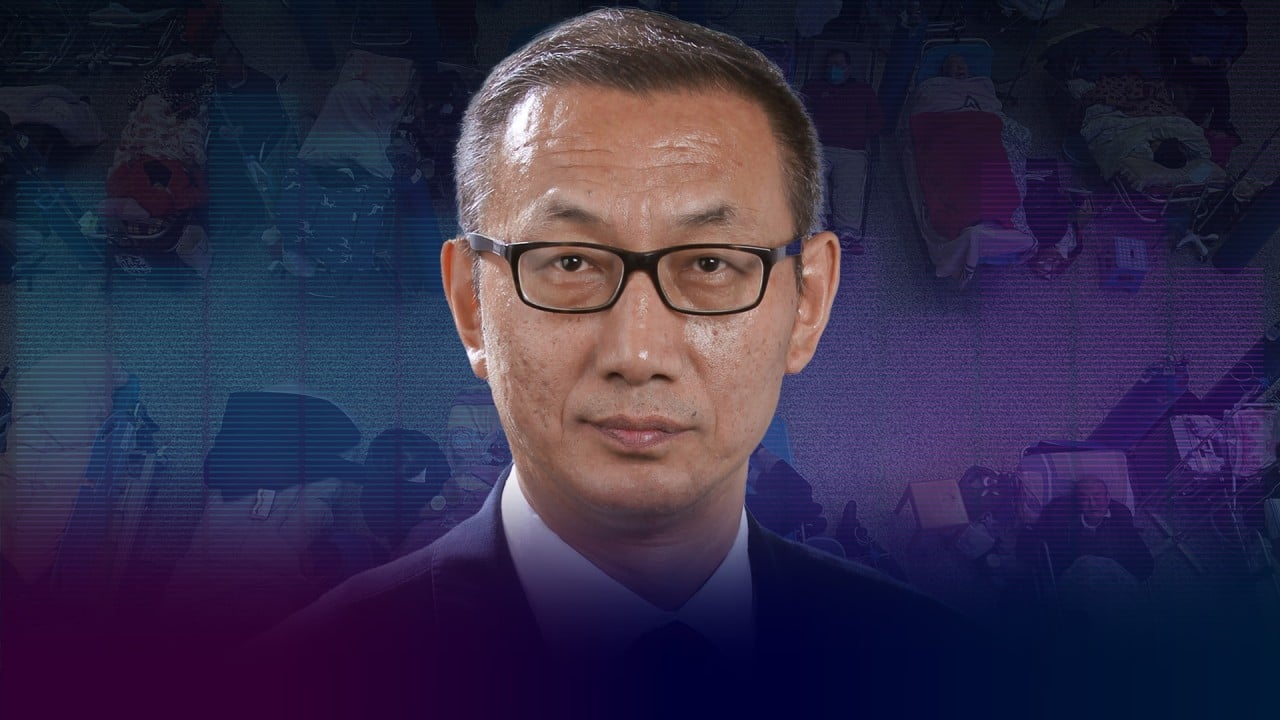

Facing an outpouring of resentment against the hasty exit on social media platforms, Jiao Yahui, a department head at the commission, told state broadcaster China Central Television on January 1 that the commission had issued a guideline early last month telling hospitals to expand fever clinics and increase the number of ICU beds and requiring communities to prepare the necessary paperwork for those most vulnerable to Covid-19 – including the elderly and pregnant – before they went to see a doctor.

The commission also asked hospitals to ensure they had enough medicines, Jiao said.

“However, the reality is the fever clinics are open, but short of medicines,” she said, “I’ve been monitoring public opinions online. I think most of the complaints are about the undersupply of medicines when people are having a fever.”

She attributed the dearth of medications to household hoarding, labour shortages at pharmaceutical factories as employees fell ill, and difficulties adapting to an abrupt surge in demand.

The remarks failed to convince many people, with thousands of negative comments posted on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media platform, criticising the lack of planning.

One said: “It’s been three years since the coronavirus erupted. Why did the preparation start in early December?”

Another asked why it was so difficult for officials to say they were sorry and called on high-ranking officials to accept public responsibility.

China Covid data shows no new variant but under-reports deaths, WHO says

George Magnus, a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre, said people were likely to “bank these experiences in their consciousness and be more wary in future”.

“If the [Communist Party’s] ambition is to order citizens and society to be compliant with and respectful of the party’s authority and wisdom, one would have to conclude that it has a very long way to go, and it may not even arrive,” Magnus said.

“This friction between the government and what seems like a lot of citizens who cannot vote in the traditional way does not bode well for social tolerance of government incompetence or failure in future.”

Jenny Wang, 36, said she was overwhelmed by sadness when she learned that her sister, who was in the third month of pregnancy, had lost her baby this month after being infected with Omicron.

“My sister couldn’t have been more careful,” she said. “She stayed at home almost all the time in the past two months, yet she was still infected.

“She was running a fever for two consecutive days without any medicine in my hometown in Anhui. She wouldn’t have lost the baby if we had not been thrown into such a disarray.”

Wang said the past couple of years had been “disastrous” for her family. She lost her job in a private tutoring company in 2021, and her husband’s pay at an internet technology firm had been cut significantly last year after both industries were subject to government crackdowns.

“But this year is worse. It’s the darkest time in my life,” she said.

Independent political scientist Chen Daoyin, formerly a professor in Shanghai, said Beijing could expect to encounter more public disobedience in future as its haphazard policy shift had stained its reputation and hurt its credibility.

“Public resentment will turn into noncompliance,” he said. “As local officials are less motivated amid financial difficulties caused by PCR testing expenses and the economic slowdown, local governments also have a low willingness to carry out the policies of the central government.

“So, if the economy fails to rebound strongly this year, we’ll probably see a stagnant China.”