China’s Chang’e moon missions and how it achieved its first lunar landing

The latest phase of the country’s ambitious programme, designed to culminate in a manned mission, is set to lift off in December

Later this year China will launch its newest lunar probe, the Chang’e 4, on a mission to the far side of the moon.

The launch in December is the latest phase of the ambitious Lunar Exploration Programme and, if successful, will be the first successful landing on the far side of the moon.

Also known as the Chang’e programme – named after the Chinese goddess who, according to myth, flies to the moon – it is part of a continuing series of missions that started in 2003.

China lifts off in pioneering journey to the far side of the moon

The whole programme is expected to take more than 20 years to complete and the plan is intended to culminate in a manned moon landing by 2036.

Here we look at how the programme has developed so far and what will come next.

Phase I: Orbiting

The programme incorporates three phases: orbiting, soft landing and sample return.

Chang’e 1

Chang’e 1 was an unmanned satellite that was sent into orbit around the moon under the first phase of the programme.

It was first launched on October 24, 2007, aboard a Long March 3A.

It left lunar transfer orbit on October 31 and went into a polar orbit on November 5. It continued in orbit until March 2009 – four months longer than initially planned – during which time it scanned the entire moon in intricate detail.

The mission helped generate a high pixel 3D map that provided a vital resource for future moon landings.

The spacecraft also helped map certain chemical elements on the lunar surface – providing a record of potentially useful resources.

China’s first space station Tiangong-1: the story of its life and death

Chang’e 2

Chang’e 2 was launched on October 1, 2010, aboard a Long March 3C rocket. It became the first lunar probe to have entered an Earth-to-moon transfer orbit without orbiting the Earth first.

It reached the moon in just under five days, compared with the 12 it took Chang’e 1.

Although the spacecraft was similar to its predecessor in terms of design, Chang’e 2 was the first spacecraft to have an advanced on-board camera installed.

After mapping the moon in November 2010, the probe moved into a different position in space to test China’s tracking, telemetry and command network.

It later conducted a fly-by of the near-Earth asteroid 4179 Toutatis in April 2012.

Phase II: Landing

The second phase of the programme saw China become the third country in the world – after America and the Soviet Union – to land spacecraft and lunar rovers on the moon’s surface.

Chang’e 3

Chang’e 3 was launched on December 2, 2013, aboard a Long March 3B rocket and made a successful landing on the moon two weeks later.

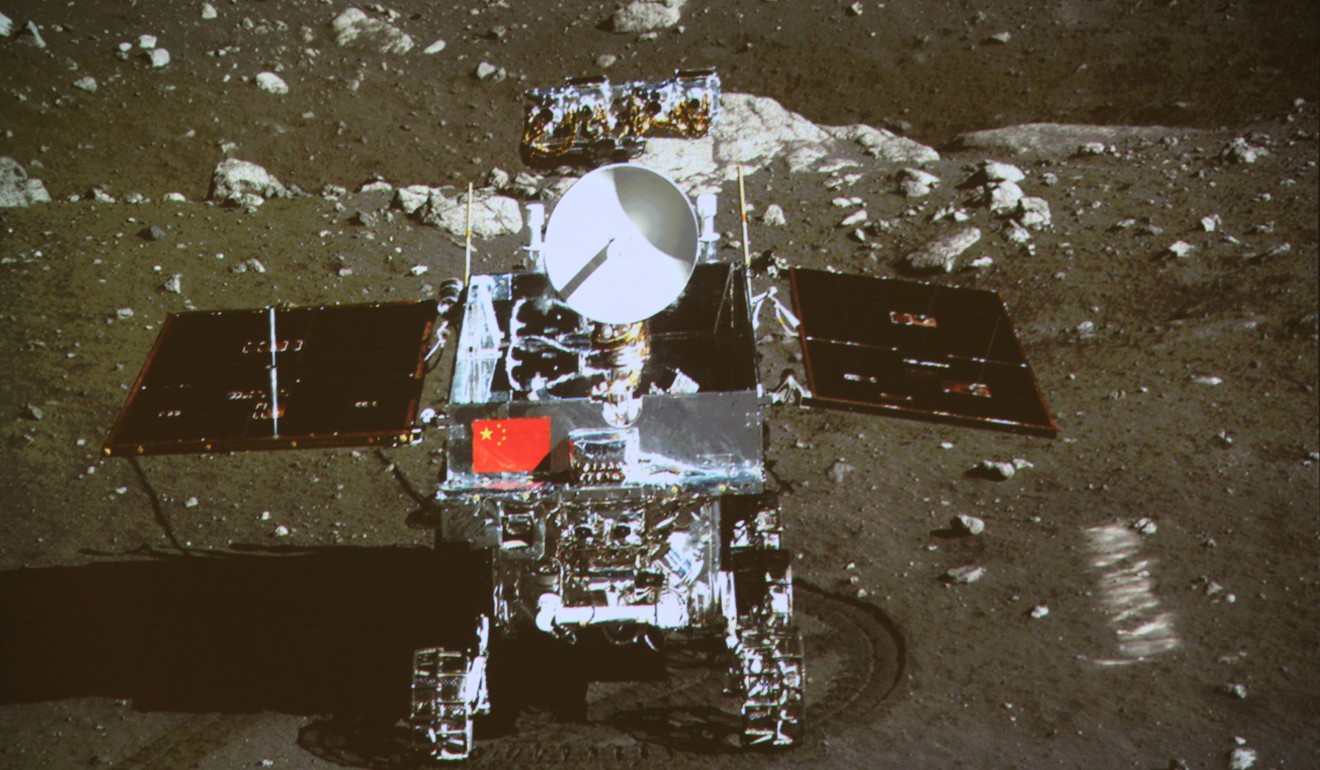

The spacecraft carried the 140kg (310lb) moon rover Yutu, or Jade Rabbit, which was named after the companion of the goddess Chang’e.

Yutu became something of a social media sensation by sending messages back to Earth and garnering over 600,000 fans on the microblogging site Weibo.

The Jade Rabbit was equipped with solar panels to provide energy, 3D stereo cameras for observing the moon surface, antennae and spectrometers on a robot arm which measured the lunar soil.

It had wheels to help it explore a 3-square-kilometre area over a three-month period, as well as carrying out observations of galaxies, stars and the structure and dynamics of the Earth’s plasmasphere.

200 days in China’s ‘moon lab’ pushes students to the lunar limit

It was assumed dead after going silent in February 2014, but later came back to life. When it did, a message was posted on its account saying, “Hi, anybody there?”

Despite mobility problems it remained active for more than two years, making it the longest-lasting rover on the moon.

Chang’e 4

Chang’e 4, which was originally scheduled for launch in 2015, saw its mission pushed back until December this year owing in part to serious problems with the Long March 5 Y2 launch rockets.

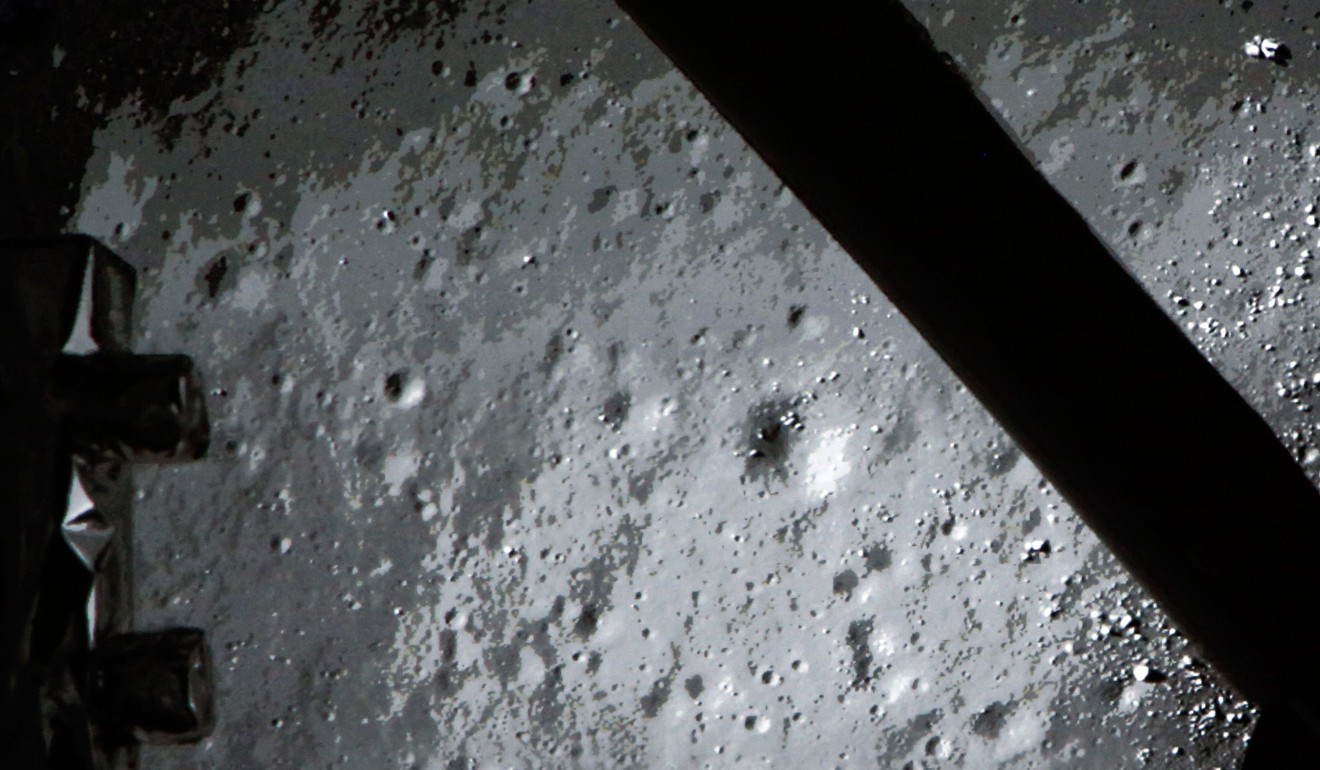

It will be the first mission to land on and explore the far side of the moon because the impossibility of directly communicating with the Earth makes it much harder to land there safely.

A major focus will be the Von Karman crater near the lunar south pole. It is thought to contain rich mineral sources including iron oxide and thorium, which could be used as a substitute for uranium.

From Mao’s vow to Xi’s ‘space dream’, China takes another step on its Long March to the moon

Because the far side of the moon never faces the Earth, scientists hope that the lack of radio interference will let them pick up electromagnetic radiation from the early universe, providing valuable clues as to its origins. Queqiao, meaning magpie bridge, a relay satellite that was launched in May, will play a critical role in Chang’e 4’s mission as it will receive information from the rover and pass it on to control stations on Earth.

Phase III: Sampling

The third phase of the mission involves collecting samples from the moon’s surface and sending them back to Earth for analysis.

Chang’e 5-T1

Chang’e 5-T1 was a precursor mission that carried out atmospheric re-entry tests on the capsule that will be used in the main mission next year.

The experimental probe was launched on October 23, 2015, and landed in Inner Mongolia nine days later.

The capsule carried bacteria and plant samples to test how they reacted when exposed to radiation during a low Earth orbit.

Chang’e 5

China’s first sample return mission will be launched some time next year after being delayed due to the failure of the Long March 5 launcher.

It aims to collect at least 2kg of lunar soil and rock samples before returning to Earth.

Chang’e 5’s moon rover will be equipped with important tools such as a robotic arm, a rotor drill, a scoop for sampling and individual tubes to separate different soil samples.

Chang’e 6

Chang’e 6 is expected to be launched about 2020 aboard a Long March 5 rocket if the previous mission goes according to plan.

It is also intended as a sample return mission and will try to build on the work of its predecessor.