Gene-editing scandal: CRISPR Cas9 method does not cause mutations in monkeys, study finds

- But technique still not fit for use on humans, Chinese researcher says

- Medical world hopes gene editing may one day provide a cure for diseases like cancer

Professor Su Bing and colleagues at the Kunming Institute of Zoology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences examined rhesus monkeys born from embryos modified by the gene-editing tool CRISPR Cas9 and found no unexpected mutations.

The experiment produced four living monkeys with a gene important for the development of the central nervous system missing.

The big gene editing mystery: where is He Jiankui?

The test was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the institute in Kunming, which runs the world’s largest facility for breeding monkeys for scientific research.

Su’s team checked the monkeys’ genes with various methods, including whole genome sequencing. Mutations were detected but “there is no evidence that these mutations were caused by gene editing”, Su said.

“And the monkey is a close relative to humans.”

Their findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications on December 4.

Gene editing has raised hopes for solving a wide range of problems, from cancer to ageing.

In recent years, numerous clinical trials have been approved by countries including the United States and China. In some trials, blood cells were taken from a patient, modified and injected back into the body to see if they could help fight cancerous cells.

But He stirred controversy in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen last year when he revealed he had used the CRISPR technology on twin baby girls to make them immune to HIV.

Scientist He Jiankui ‘may have created unintended mutations’

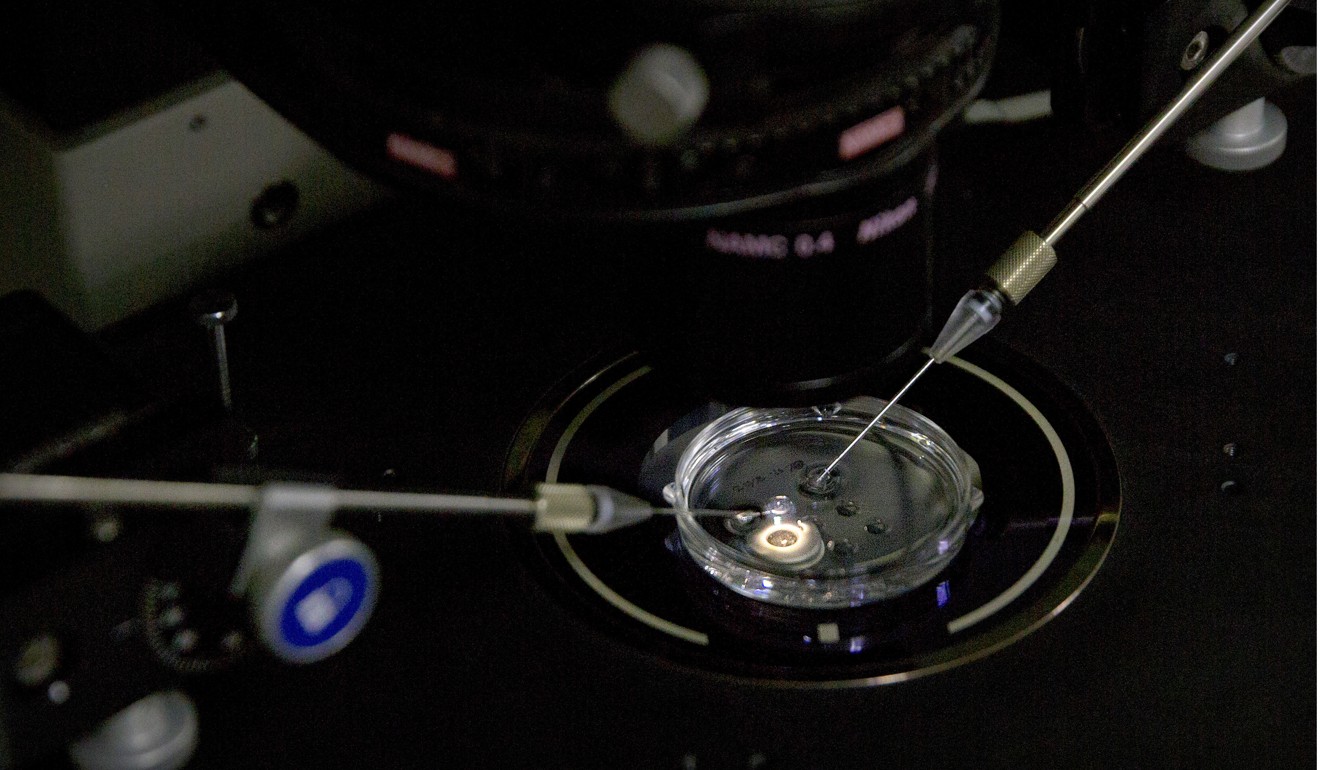

The public outcry stemmed from uncertainty over the safety of CRISPR, a genetic “scissor” that can delete unwanted genes or introduce new ones to the DNA. CRISPR has a guidance device like GPS that takes it to specific areas of a person’s DNA. To carry out the modifications, it then cuts the DNA apart and relies on the cells’ self-healing mechanism to rejoin the broken strains.

In theory, lots of things can go wrong. The GPS guidance, for example, might get lost and drop the scissors at the wrong location. The repairs might introduce errors as well, which could cause unexpected mutations and illness.

Previous experiments on rodents and human cell lines produced mixed results. A study by Stanford scientists in 2017 found the problem of rampant off-targeting on rodents. But attempts to replicate the results around the world failed, and the paper was retracted the next year.

Some scientists also observed alarming changes on human cell lines, but whether these results were reliable has come under debate as well because some chemical solutions used to stimulate cell growth in these experiments are known to encourage mutations.

China tightens rules on genetic research after designer baby scandal

Su said their study provided critical data for research teams around the world considering carrying out experiments on humans in the future.

“Rodents and cell lines have some serious limits,” he said. “Monkeys provide us with the best reference because they are as close a relative as we can get in animal experiments.”

But he said the results did not mean that the safety of CRISPR could be taken for granted and be immediately applied to human beings. Though the team’s genetic analysis was relatively comprehensive, there was still a chance that some mutations might have been missed.

Also, Su said, the results could not be used to justify He’s controversial experiment.

“Quite the contrary,” he said. “Our study suggests that animal experiments should be carried out before using the technology on human beings, otherwise it is bad science.”

Gene edited babies face risk of premature death

Su’s study prompted heated debate. Kong Daochun, professor of life science at Peking University and editor of the journal DNA Repair, said gene editing would “definitely miss some targets” and the cell’s healing mechanism was not 100 per cent reliable.

It would take a long time to “check and compare every letter in the DNA”, he said.

“Existing sequencing technology has a resolution limit. We can’t say gene editing is safe based on these results. Using this technology on humans, especially children, could lead to disaster.”

Wang Yongming, a professor of life sciences at Fudan University in Shanghai, said he was optimistic about the future clinical use of the technology.

“Gene editing will never be perfect. Nor are the drugs on shelves. They all have side effects,” he said.

“If a patient’s life is under threat, he may be willing to take a risk, if the benefit is greater than the cost.”