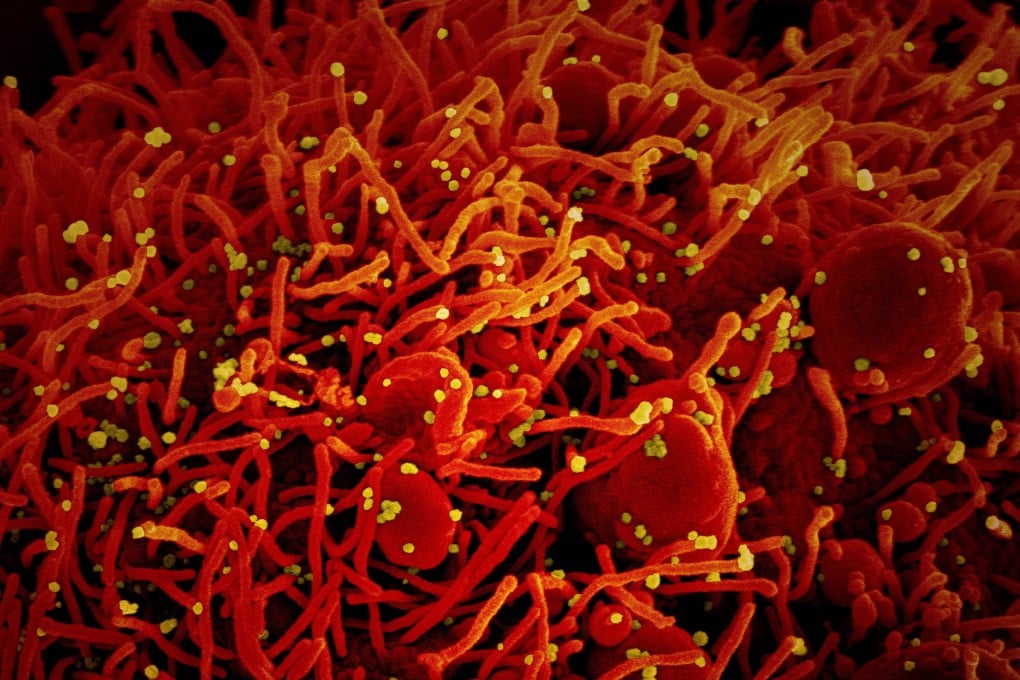

No sign of big mutations in coronavirus strains, study finds

- Italian researchers say there is little difference between the varieties circulating worldwide but monitoring should continue

- Results bolster prospects for a vaccine to fight the pathogen, co-author says

Researchers from the University of Bologna in Italy examined 48,635 genomes of Sars-CoV-2, the official name for the virus that causes the disease Covid-19, collected by labs from around the world and published the results in a paper in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Microbiology at the end of last month.

The researchers identified six strains of the virus but found no significant clinical or molecular differences between them.

“The Sars-CoV-2 coronavirus is presumably already optimised to affect human beings, and this explains its low evolutionary change,” Federico Giorgi, assistant professor of bioinformatics at the University of Bologna, said.

“This means that the treatments we are developing, including a vaccine, might be effective against all the virus strains,” said Giorgi, who coordinated the study.

06:17

‘Robust immune responses’ found in Covid-19 vaccine clinical trials point to 2021 release

The six strains of the virus included the L strain, the one first reported in the central Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019.