Into the unknown: virus hunters and their quest to stop the next pandemic

- Experts estimate that there could be more than a million viruses with potential to infect humans but very few have been catalogued, much less studied

- Greater understanding of these pathogens might have better prepared the world for the Covid-19 epidemic but research has been held back by a range of factors, including a lack of funding, they say

The start date and members of the mission remain unknown but one thing is clear: the scientists will be confronting a huge gap in knowledge about what viruses are out there and how they make the leap to humans.

Researchers estimate that there could be more than 1 million viruses with the potential to infect humans and the technology exists to get a clearer picture of what’s out there and where the risks are.

But so far only a small fraction of those pathogens have been catalogued and there is limited capacity to monitor how they show up in humans, with progress held back by a lack of funding, international coordination and political will, they say.

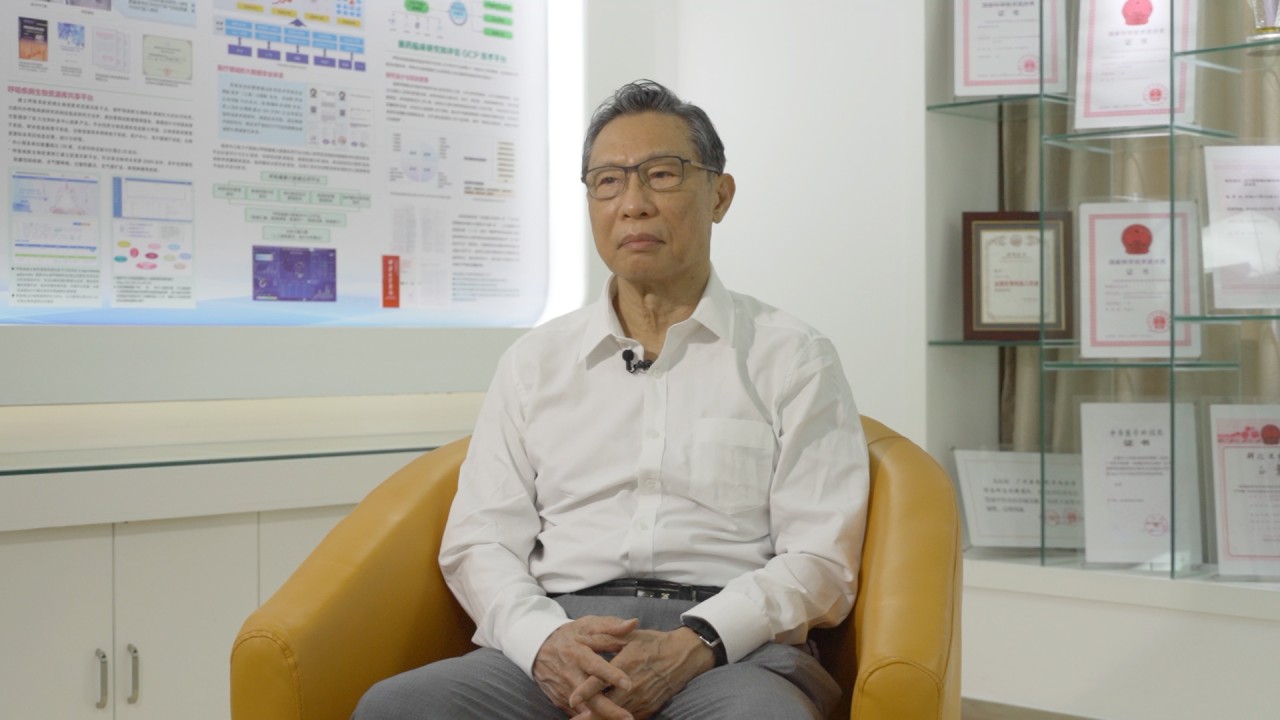

Wang Linfa has been this way before.

He said that while there was still much to understand about these pathogens, the world should be better equipped to handle this one, especially with the emergence of two related coronaviruses in two decades – Sars and Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers).

“Some of them are ‘unknown unknowns’,” Wang said. “But Covid-19 is a known unknown.

“We already knew [these viruses] can kill humans … we could have done much better.”

Scientists have long warned that the risk for such spillovers is growing alongside humanity’s expanding footprint, a point made again by WHO Health Emergencies Programme executive director Mike Ryan earlier this month.

“We live on a planet in which we’re adding a billion people a decade. We are densely packed, we’re exploiting pristine environments, we are creating and driving the ecologic pressure … that [is] driving the risk at the animal/human species barrier,” Ryan said.

03:21

Chinese respiratory disease expert on origins of Covid-19 and Wuhan virus lab conspiracy theories

Virus hunters have been hard at work around the world trying to better understand the viruses lurking in nature and how humans put themselves at risk of infection.

For example, researchers involved in the US-funded PREDICT project spent a decade ramping up global capacity to find viruses with “pandemic potential”.

They identified around 1,000 novel viruses during the programme, which was set to end this spring, but received a six-month extension due to Covid-19. Chinese researchers whose institute was involved in PREDICT gave scientists the best clue they have on the origins of the novel coronavirus – a bat virus with 96 per cent similarity found in a cave in southwestern China.

But that 4 per cent is a huge difference.

“A chimp is 96 per cent similar to a human,” said Jonna Mazet, who was global director of PREDICT.

That big genetic gap between the novel coronavirus and its closest known relative in the wild shows just how many more viruses there are to find.

Mazet, also a professor of epidemiology and disease ecology at the University of California-Davis school of veterinary medicine, said that if a wide spectrum of viruses were already known and catalogued the job of finding a new virus’s origins would be much easier.

“We would have that data ahead of time and we wouldn’t have to be doing this very difficult retrospective action,” she said.

“We know about 0.2 per cent of the viruses that are out there and likely to be able to infect humans,” she said. “Not even 1 per cent.”

Mazet said that it was important to know not just how Covid-19 emerged but what else among the legions of viruses had the potential to become a pandemic.

“You can’t prevent if you don’t know what you are preventing,” she said. “You have to do the science to understand what’s out there.”

This means hi-tech work in biosecure laboratories, checking for known and unknown viruses in the blood, saliva, and faecal samples collected from bats and other animals and testing blood, including from humans, for the traces of previous infections.

This also involves low-tech work like surveys to see how daily routines bring people in contact with potentially deadly pathogens or putting cameras in the wild to know, for example, which animals might be eating fruit infected with virus-laden bat saliva.

That is a technique being used by virus hunter Wanda Markotter, director of the Centre for Viral Zoonoses at the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

She has tracked bat viruses related to the ones that cause deadly diseases like rabies and Ebola. It is too soon to know if her country is a hotspot for Sars-like coronaviruses, according to Markotter. Her team had not found any yet, “but I’ve only tested 200 horseshoe bats”, she said.

One barrier to preparations for threats from these viruses is that some of the grant funding for the necessary research has had inbuilt limitations. In addition, governments might not support basic, ongoing biosurveillance.

Markotter said technical complexities and limits on time and funds meant researchers did not always have the capacity to test for multiple viruses in one study, or see if they were present in other species, like humans and intermediary hosts.

“Just sampling and testing bats is not going to help you prevent and predict, you need much more than that,” she said.

Meanwhile, some studies involved international teams entering a country to collect samples, but there might be no resources locally to continue the work over the long-term, according to Markotter. All of these issues can make it difficult to understand the broad picture.

“If we do proper studies [with] seasonal surveillance … and use genetics to guide us on what we think are the more dangerous [viruses] that may spill over, we can make an informed decision on which are the ones we should watch,” she said.

Markotter said funders had been calling for broader studies in recent years but more had to be done to connect the dots between collecting samples and understanding spillover risk within an ecosystem. There was even more work to do to use that information to start developing vaccines and diagnostics for future outbreaks, she said.

“I really hope this [Covid-19 pandemic] is a proper wake-up call,” she said.

02:24

Coronavirus: A look inside China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology

But this year has already seen a setback – US funding for a long-running research project into the risks of bat coronavirus emergence in China was suddenly cut this spring by the US National Institutes of Health. Though the grant was later reinstated, the funding was suspended until certain conditions could be met, according to a statement from the research group running the programme, who said the terms will “effectively block” the work.

The group, the New York-based non-profit research group EcoHealth Alliance, had long-standing collaborations with the Wuhan Institute of Virology and had provided them with funding in the past.

Wang in Singapore, who works with EcoHealth and was formerly on the institute’s advisory board, said the decision to cut the grant was “going in the opposite direction” of what needed to be done globally.

“Hopefully that’s transient and not the trend, because if the world goes that way in the future then I think we’ll be in trouble,” Wang said.

Being prepared for future pandemics meant being able to do “transparent disease risk assessment across borders”, he said.

07:54

Six months after WHO declared Covid-19 a public health emergency, what more do we know now?

The WHO mission might be a step in that direction. Finding a virus that is 99 per cent similar to the one that appeared in humans could require international collaboration to look in and out of China, because the virus could have crossed borders such as via the wildlife trade, Wang said.

But in the big picture, too, scientists hope the Covid-19 pandemic will galvanise world leaders to make biosurveillance of viruses and spillovers a higher priority.

David Morens, senior adviser to the director at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the threat posed by pandemics should be seen “on par with” nuclear and chemical weapons and preventing them required joint effort.

“Isn’t a pandemic threat as much an existential threat … why do we not take it as seriously as we do nuclear and chemical [weapons] prevention and put the resources towards it?” he said.

“Pandemic prevention is an international effort, one country can’t do it alone.

“The information is out there, and we have scientists who can gather it and interpret it … [to] help us prevent or at least control the early phases of these emergences,” he said. “We have to do it.”

Mazet is part of an initiative known as the Global Virome Project, which aims to catalogue most of the unknown viruses with potential to infect humans, a project that would require international data sharing.

She said she hoped the nationalism that had risen up in response to the pandemic could be overcome in favour of working together.

“All evidence suggests that we are increasing almost exponentially our risk and the number of viruses that are spilling over to people,” she said. “Hope is not a plan.”