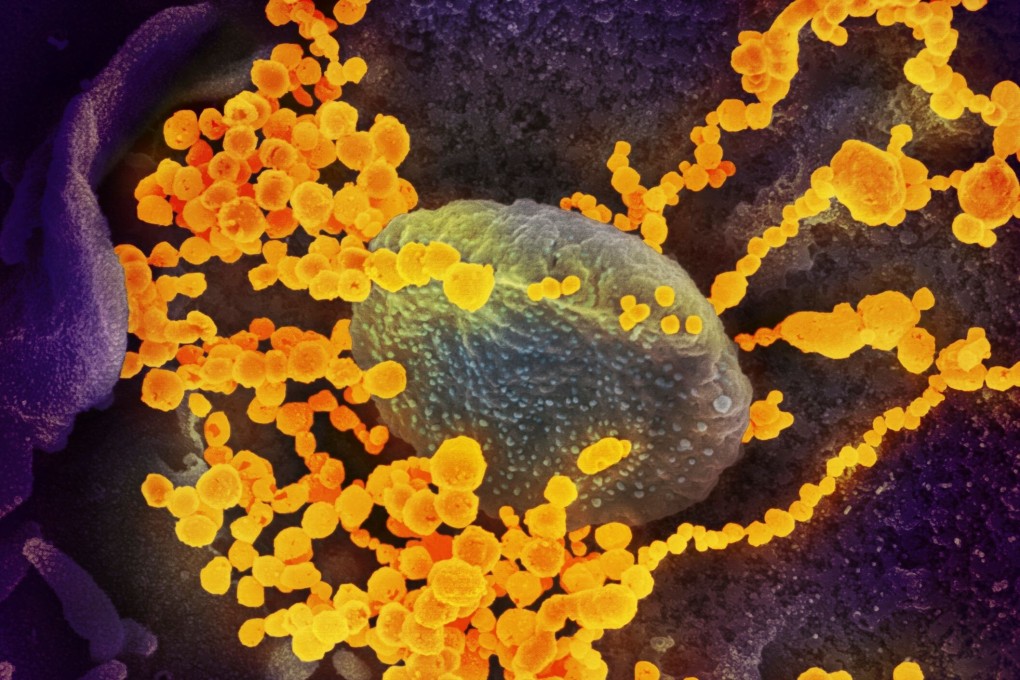

Study on infant in Brazil suggests coronavirus ‘does not efficiently spread into brain’

- Researchers found a concentration of the virus in just a small part of one-year-old’s brain, indicating it may have limited ability to reproduce there

- But it could still cause infection and trigger an immune response that would damage tissue, according to non-peer-reviewed paper

But it could still cause infection and trigger an excessive immune response that would damage brain tissue, according to the study, led by neuroscientist Stevens Rehen from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

The researchers concluded that the coronavirus “does not efficiently spread into the brain”, in a paper that has not been peer-reviewed posted on preprint server bioRxiv.org on Monday.

Children are less likely to get infected with the virus or develop severe symptoms than adults – though much is still unknown about how it affects them.

However, soon after the first strain of the new coronavirus was identified, Chinese doctors found it could make some children seriously ill. The first child case was confirmed on January 20 in Wuhan, and by February 2 more than 700 children had been treated in hospital for the illness across China, according to a study by Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The youngest was just 55 days old.

Although symptoms in children are generally mild, in China about 10 per cent of infants under 12 months infected with Covid-19 have become critically ill or died from the disease.

06:14

Countries that haven't reported a single case of Covid-19 are still hit hard by the pandemic