Air pollution improved during China’s lockdowns – and it may have reduced hospital visits

- Lower levels of harmful PM2.5 particles could have resulted in an estimated 5,000 fewer hospital admissions from late January to February, study finds

- Researchers also estimate there were 60,000 fewer respiratory illnesses like asthma attacks in the period

Reduced levels of the tiny hazardous particles known as PM2.5 were likely to have resulted in an estimated 5,000 fewer hospital admissions and 60,000 fewer respiratory illnesses, like asthma attacks, from late January through February, according to a team of researchers from China, the US, Japan and the Netherlands.

In China, which has aimed to improve its notoriously poor air quality in recent years, the health burden is steep. Air pollution caused an estimated 1.24 million deaths there in 2017, according to an analysis for the University of Washington in Seattle’s Global Burden of Disease study published this year.

03:31

Coronavirus: blue skies over Chinese cities as Covid-19 lockdown temporarily cuts air pollution

“These results give us a window into what a cleaner world could look like – and the paths needed to achieve it,” said lead researcher Kazuyuki Miyazaki, a scientist in the Tropospheric Composition Group at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology.

The peer-reviewed study, published this week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, also had implications for outbreak management, the researchers said.

“This is the first study to show that the decreased air pollution during a lockdown can reduce demand for hospital beds and services and keep them from being overrun, which is one of the main short-term goals of flattening the curve,” said earth science professor Drew Shindell of Duke University in the US, one of the study authors.

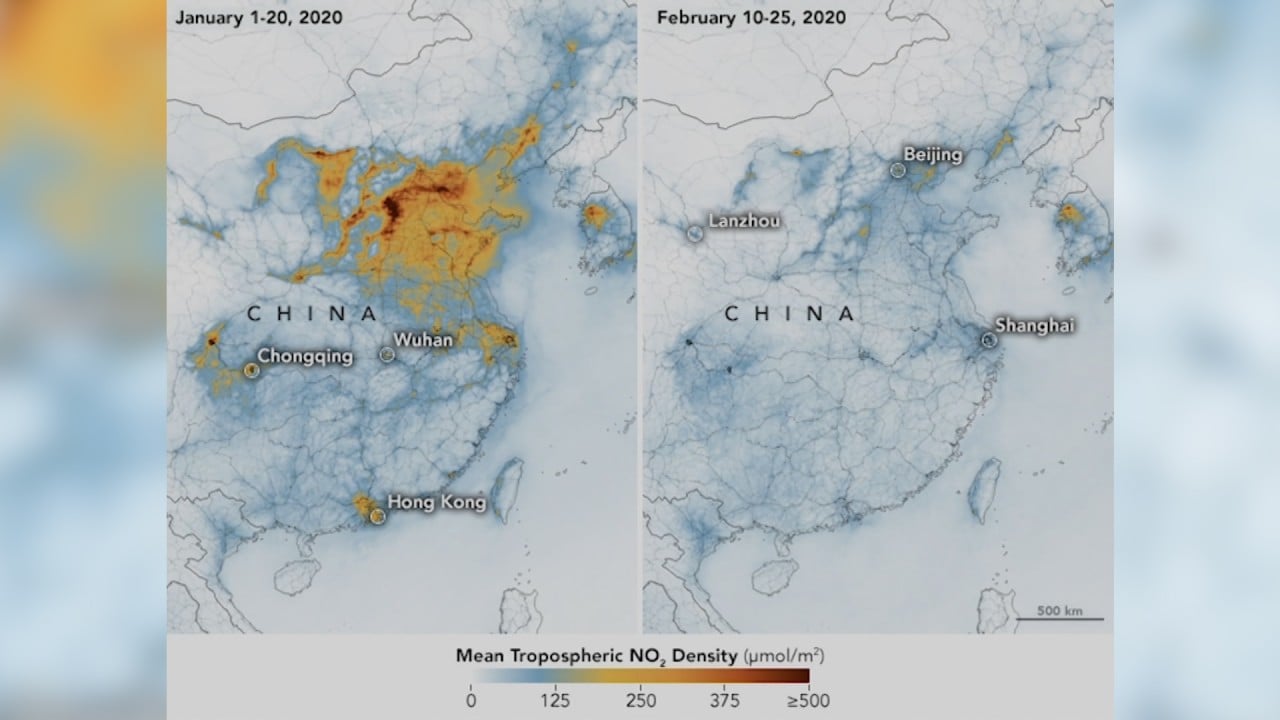

The researchers found there was a 36 per cent reduction in nitrous oxide emissions from early January to mid February, which significantly reduced the levels of PM2.5 in the air. They used this data to project the impact on the number of hospitalisations linked to respiratory or cardiovascular illness.

Lao Xiang-qian, an associate professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Public Health and Primary Care, said the study’s conclusions were convincing, given the well-established relationship between exposure to air pollution and poor health.

“Investigators might conduct a further study in future to confirm this finding, if they can get data on the number of respiratory diseases and hospitalisations,” he said.

Coronavirus: WHO waits for China to approve pandemic origins investigators

Shyamali Dharmage, head of the allergy and lung health unit at the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, said it would also be important to study the implications of air quality changes during the lockdown period over the longer term, such as the effect on children born during “low pollution periods”.

“Early life is a critical period for development of lungs, and Covid-19 lockdowns can be used to investigate the impact of reduction of air pollution levels during the first few months of life,” Dharmage said.

Given the high levels of air pollution in China, such reductions during lockdown would have been substantial and likely to have a beneficial effect on respiratory health, she said.

Several other studies have investigated the health impact of the decrease in air pollution during China’s lockdowns.

Researchers at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology estimated that about 24,000 to 36,000 early deaths due to air pollution may have been delayed because of lockdowns on the mainland, in a July study published in the journal Nature Sustainability.

Lead researcher of that study He Guojun, an assistant professor of social science at the university, said that while lockdowns could have short-term health impacts due to improvement in air quality, they also “bring about significant health costs, particularly in the long run”.

Covid-19 lockdowns brought blue skies back to China, but don’t expect them to last

These may arise from limited access to health care for those with chronic disease, as well as from the economic impact of lockdowns.

China’s lockdowns ended in phases through mid-April, and by June, daily consumption of coal, oil and gas was on par with that of the previous year, according to the government.

He said there were lessons to be learned from the lockdowns.

“The government should continue to improve air quality,” he said. “It definitely does not mean lockdowns should be sustained to improve public health.”