Production of Covid-19 vaccine could top 16 billion doses, but delivery is still a challenge

- Manufacturing limits, a nation’s health care system and intellectual property rights could all affect which countries receive vaccines and how quickly

- Of 16 billion doses manufacturers expect to make next year, over 8 billion have already been committed to countries

But failures and setbacks are standard in the vaccine industry, and such projections could be cut by more than half, according to another estimate made last month.

Which experimental vaccines do eventually make it past approval and off assembly lines at scale will have a profound impact on who gets vaccinated and when, as large amounts of some companies’ supplies have already been claimed by rich economies, or have been pledged to lower and middle income economies.

Meanwhile, a global plan to equitably distribute doses is still in the process of securing shipments and funding. Some countries say intellectual property rules will hinder them from using their own manufacturers to make up for any shortfalls. Others do not have the infrastructure to deliver certain vaccines, even if they arrive next year.

All this sets up the potential for a wide disparity in early access to vaccines for the global population, and health experts around the world are concerned.

“The [face] mask is the vaccine for Bangladesh for [the] next 24 months at least,” said Sayedur Rahman, a member of the Bangladesh National Research Ethics Committee that reviews clinical trials. He said his country of 160 million people and other poorer nations might be priced out of the first vaccines available, making other disease control measures their only option.

“The vaccine won’t be affordable or actually available in our country for the next 12 to 24 months, and even if it becomes available, it will be available to very limited number, a maximum of 20 per cent of the population,” said Rahman, a professor of pharmacology at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University.

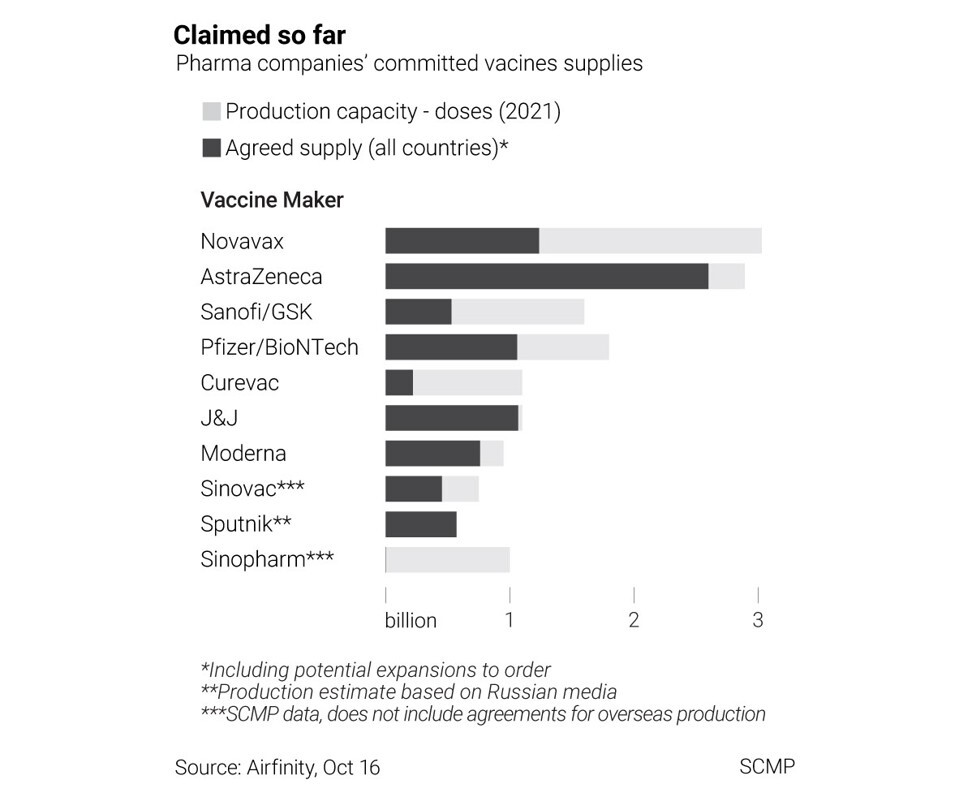

Of the 16.3 billion doses that manufacturers have said that they could produce next year, some 8.6 billion are already tied up in supply deals, according to data from the British life sciences analytics firm Airfinity in mid-October.

Less of the 1.6 billion-dose capacity by China’s pharmaceutical companies has been committed, at least publicly, than that of the leading US and European companies, according to Airfinity data. However, China’s government has promised priority access for a number of lower and middle income countries.

But all these plans may face setbacks, according to analysis last month by European-American think tank the Yellow House.

Of the 12 billion projected or planned doses the Yellow House tallied in September for production by the end of next year, only a third to a half might actually materialise, they forecast after taking into account historical failure rates in vaccine development for clinical trials, as well as possible setbacks when boosting production.

John Donnelly, a principal with US firm Vaccinology Consulting, said that while scientific data released by a number of vaccine makers looked promising, there could be delays in ramping up output for approved vaccines.

“Inevitably there are going to be hiccups, so I’d be pretty surprised if the theoretical target could be met,” Donnelly said. He pointed to a number of potential challenges, including running out of raw materials or delays by manufacturers that were not typically focused on making vaccines.

“The winners and losers might be decided by the robustness of their manufacturing process rather than by the effectiveness of their product,” he said.

Coronavirus vaccine race: where are we and how far?

About half of those are lower and middle income countries that are eligible for their doses to be financed through donations, in addition to a likely cost-share of US$1.60-$2 per dose. The others are countries that pay into the facility for their doses.

The programme aims to distribute the vaccine in equitable tranches to cover an initial goal of 20 per cent of countries’ populations, which it says would end the acute phase of the pandemic.

This is the average proportion of the population made up of the most vulnerable groups – health and frontline workers, elderly populations and those with pre-existing conditions – according to a spokesperson for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation-backed organisation leading the Covax programme.

“Once all economies have reached 20 per cent coverage, a ‘weighting’ exercise will consider if some countries should receive doses more quickly than others,” the spokesperson said. The weighting will include factors such as public health needs and understanding of transmission and risk.

Yvette Madrid, a Switzerland-based global health consultant, questions if the initial doses will be enough to make a difference globally.

Can China become a leading producer of Covid-19 vaccines?

“If Covax was going to fulfil its ambitious vision, you would want it to have most of the doses available, not a fraction of them,” Madrid said. She said if billions of doses were available next year, a large proportion could still end up concentrated in the countries and blocs that have their own deals with manufacturers, such as the European Union, Britain and the US.

Meanwhile, disparities between countries’ health care systems, such as some lacking proper refrigerated equipment required to store some vaccines, might mean they could not handle early available supplies, said Madrid.

This month, India and South Africa suggested another means to make sure lower and middle income countries get necessary supplies.

The proposal won the backing of the WHO and more than 400 health and social organisations from around the world. But some countries opposed it, saying the same end could be achieved in other ways, such as joint agreements between vaccine developers and manufacturers, a practice already in use for Covid-19 vaccines.

But Deborah Gleeson, a senior lecturer at the School of Psychology and Public Health at La Trobe University in Australia, raised her concerns. Relying on vaccine developers in wealthy countries to produce the products for the whole world is “not only impractical in terms of the volume of products that can be produced, that also allows them to set prices that puts it out of reach”, she said.

This issue will also matter for countries taking part in Covax, since it only aims to cover 20 per cent of countries’ populations initially, she said. Getting enough doses to cover countries’ populations in the long and short term will require other solutions, including sharing intellectual property.

“Unless [countries] actually support mechanisms that enable sharing to happen, then we just end up falling back to the way things have always worked,” she said, which meant richer countries get wide access to medicines and vaccines, while the poorer ones wait or are priced out. “That hasn’t served us well.”